The Oracle at the Top of the Stairs

An aspiring writer meets Walker Percy

Published: November 30, 2020

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

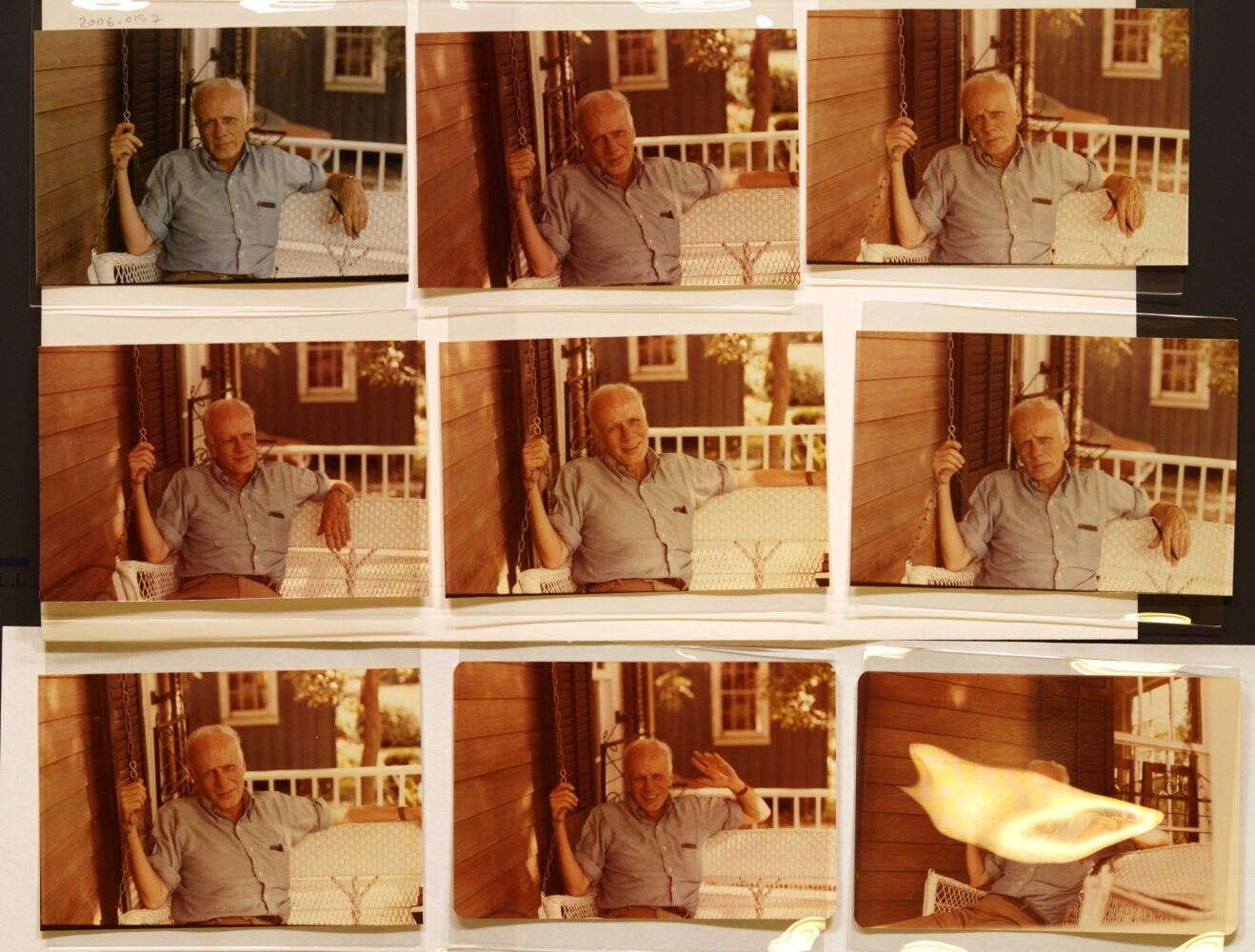

The Historic New Orleans Collection

Walker Percy at home in Covington.

Dead, lingering silence. Another rejection? And then, a flat “Come in”: the tone of a man being disturbed and saying so. Percy was friends with Eudora Welty and Shelby Foote, and here came I, a young, isolated writer desperate to the verge of incivility, cold-calling. Scared but not caring, I pulled open the door, saw on the heart pine floor a trail of dead leaves blown in, some crushed, some crisp, and wondered why Walker Percy had left a mess gathering underfoot. I had a lot to learn.

The room was dusk at mid-morning, and as silent as sunset, until the sound of furniture creaking alerted me to the form of a man on his back on a sofa, knees bent, and then, as my eyes adjusted, with pen in hand on a spiral notebook pressed to his khaki thighs for a writing stand. The white head turned and the form unfolded, long legs pitched off the sofa, feet found the floor, man stood, notebook held like a serving tray as the author of The Moviegoer scrutinized me as if I were a soul in need of charity.

I could not hold his gaze and looked away—an upholstered sofa, a small dark table, with manual typewriter, a fat manuscript, two stuffed chairs for receiving interlopers—an ascetic space filled with an absence of things. Other than meager furniture, nothing else populated that tiny universe that ended at bare walls.

Percy inclined toward me. “I’m Bryce Moreland,” I managed, “from Baton Rouge,” and stopped like a man struck dumb. Percy, a gentleman, offered his hand, a big hand with big veins on the back like a working man’s, but smooth, and he wrapped mine as though he were grasping a puppy. He gestured to the chairs. I sat, back straight, as he settled his lank body in the other chair, draping hands over the ends of the arms.

And there it was, that silence, expectant, unbearable, pressuring me to declare, “I’m a writer,” and Walker Percy took it from there.

He said, “I tell everybody who asks me that they should not be a writer”—and I sensed this would be a short conversation in which I would have little to say.

He elaborated that it was because he had inherited money. “It took me twenty years to get published,” he said, “and without that inheritance I could not have devoted my time to writing.”

He shrugged as though to say happenstance, as much as talent, can be decisive. He then repeated: “I tell everyone who asks that they should not be a writer, and those who listen to me, I have saved from a fate not theirs, and those who are going to be writers are not going to listen to me anyway. They figure it out, do what it takes.”

He stopped, let the words hang, take it or leave it, up to me.

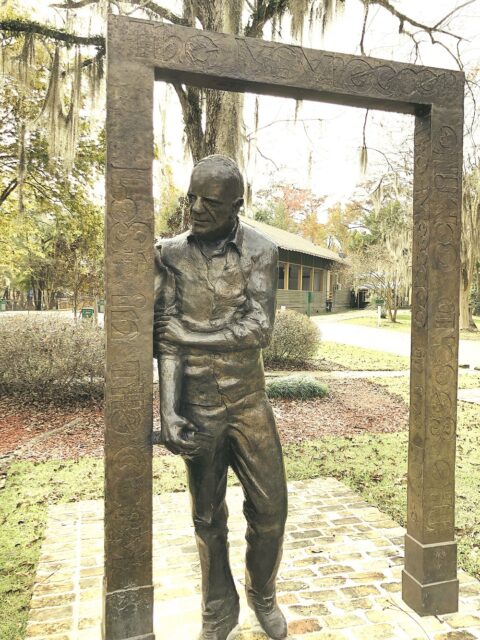

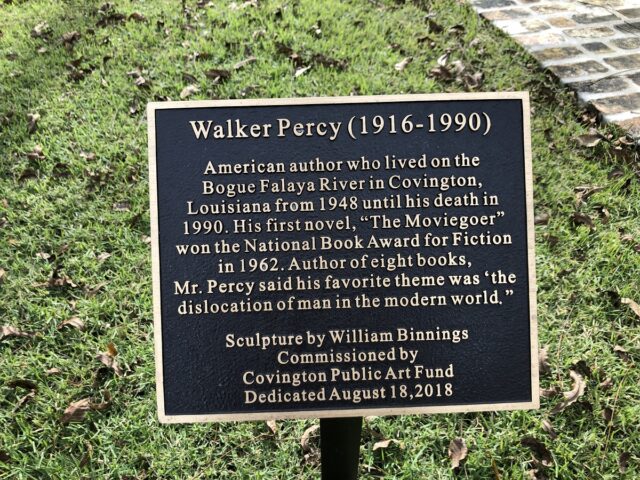

A statue of Percy now stands in Covington, marking the author’s connection to the Northshore city. Louisiana Northshore

I had nothing to say, only an uncertain nod. Figure it out? Do what it takes? Simple, direct, and to the oracle, unambiguous. Not to me. Would I keep putting my family in financial harm’s way? We had two young children and scraped by. Was I that determined? That self-centered? If I manned up—either way—wouldn’t somebody lose?

Having disposed of my supplication, he was now looking not at but beyond me. Abruptly he reached for the dog-eared manuscript beside the typewriter, hefted the stack with both hands, and let it drop with a thud. “Now what am I supposed to do with this?” he asked, sounding put out and resigned. “It’s the manuscript of a novel. An old lady, the author’s mother, she put it in my hands. She sent this manuscript to many editors in New York. This is the only copy. One copy! No other exists! And they all rejected it. It’s a miracle they returned every page.”

He shook his head just barely, incredulous at the circumstances. A mother on a mission. Hawking her son’s manuscript between New Orleans and New York. Defying all odds against the US Post Office delivering the irreplaceable to the targeted editor’s office and bringing it home again, again and again. Up and down Broadway and Fifth and Sixth Avenues, one publishing house to the next. Up elevators, down halls, editor to editor, each passing their maddening judgement. No, no, and no. And back to this pushy mother, and now here, its last chance, the spartan study of Walker Percy.

A statue of Percy now stands in Covington, marking the author’s connection to the Northshore city. Louisiana Northshore

“Her son wrote the novel,” he said, and looked away. “He killed himself.” A long pause. “She just will not give up,” and he stopped in the middle of the story. And there I was waiting, the old lady waiting, the manuscript waiting, and I felt that he knew the end of this peripatetic tale was his to write. Compassion snared him and he was steeling himself to read—one paragraph if it was bad, an indeterminate number of pages if it was not bad enough, and the whole thing if—surely not possible?—it was good.

He looked me right in the eye. “Send me your story,” he said, and jotted down a mailing address.

I had been served notice and was going to get what I asked for, soon. But the old lady would have to wait a bit longer. The title and byline on the manuscript Percy had dropped unceremoniously on the table, A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole, meant nothing to me but that a long-suffering writer had gone unrewarded to his grave.

I thanked Percy and left him to his work. He was a gentleman. I had not deserved his time, yet he gave it.

Three years later, I read about Toole’s Pulitzer on page 2A of the Morning Advocate. Percy had interceded with Louisiana State University Press, which published the book.

“I tell everyone who asks that they should not be a writer, and those who listen to me, I have saved from a fate not theirs, and those who are going to be writers are not going to listen to me anyway.”

Percy’s handwritten letter to me is dated December 10, 1977, three months after my visit, and I treasure it: The straight shooter takes aim, pulls the trigger, and puts a rubber bullet right between my eyes, not fatal, but hard-hitting enough to knock sense into me.

The letter begins “I read Bayou Terre . . . with interest” and ends with “Sorry I can’t be more encouraging, but I feel obliged to give you what you asked for—an honest feedback. Of course I could be wrong.” Of course he wasn’t. I knew it, suspected it going in, and now it was official.

I gladly quit fiction, cold turkey and good riddance. I had been long burdened by the pernicious notion that fiction is the alpha and the omega of “being a writer” and labored too hard to push that rock uphill. Civil War historian Bruce Catton, whom I admired for his lucid prose and story-telling verve, had shown me that the best nonfiction writing is as satisfying as the best fiction. And then there was my messenger, a writer and teacher at Valparaiso University, who wrote me that my description of a Black laborer swinging a sledge hammer read like poetry. So I reworked it. My first poem published in a literary journal. There have been more. Travel writing followed. Travel & Leisure and Better Homes & Gardens took my stories. One evening, I was in bed when the phone rang. The travel editor of Better Homes was somewhere on the road and called to talk. I was most encouraged, saw a globe-trekking career path opening up, my two-thousand-word stories growing to two-hundred-thousand-word books, travel stories told in first person.

I weighed my next moves for a month or so, until Margaret, my wife, encouraging always, unaware of my pondering a passport, nudged me in bed when the second baby started crying. Both were sick, and it was my turn to clean up puke and poop. By the glow of a night light, I divined, as if through the entrails of animals, the stuff of life and saw my right path.

I took a job writing employee publications for a big bank. In time, I started my own writing business and called it corporate communications. It paid well.

And I wrote poetry, cursed every rejection, and wrote another poem.

Degrees in English and journalism landed Bryce Moreland writing jobs out of college. He was a staff writer for the Louisiana Tourist Commission, freelanced for Travel & Leisure, Better Homes & Gardens, and other national magazines, produced employee publications for a big bank, and opened a PR business with clients in business and industry. Now he’s an entrepreneur in the LED lighting business. All the while he’s been writing poetry. He and his wife Margaret, a fine art conservator, live in Baton Rouge, with children and grandchildren near and far.