Democracy & Media

The Queen Bee of Louisiana Politics & the Misinterpretation of Nice

The there and back again story of Kathleen Babineaux Blanco

Published: December 3, 2018

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

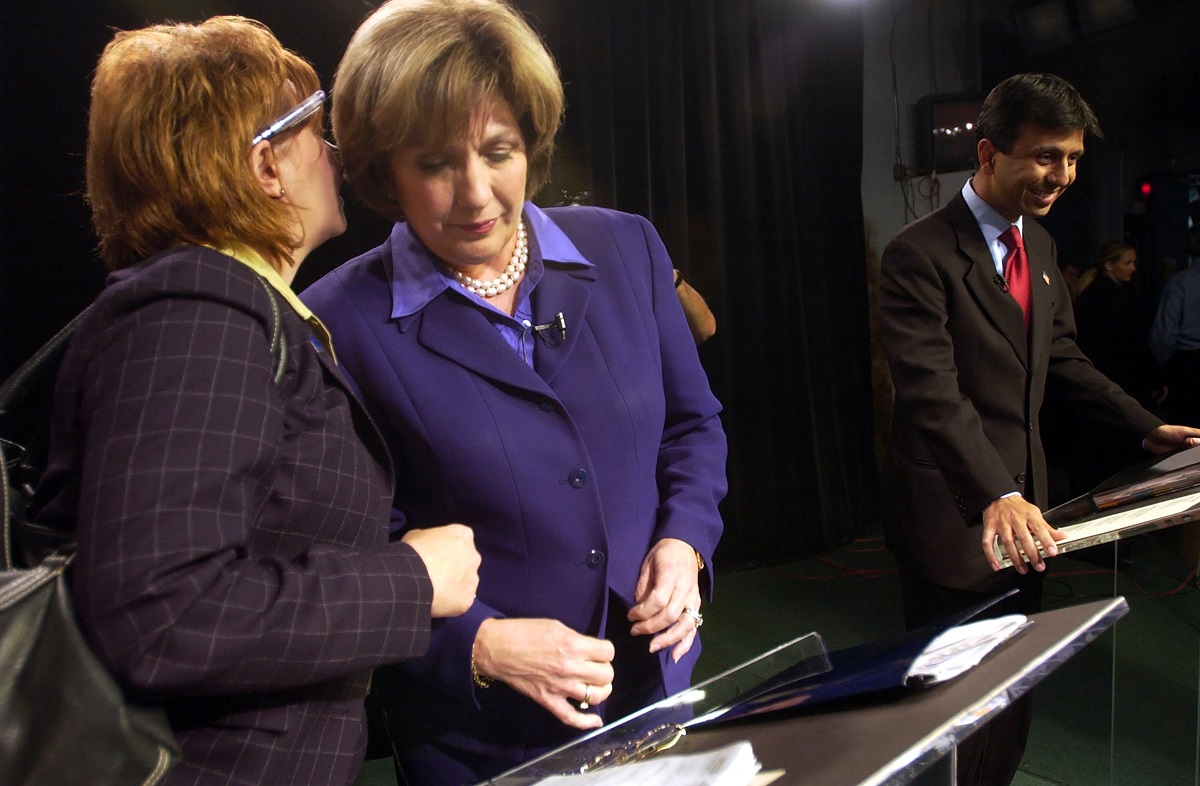

Baton Rouge Advocate / Richard Allan Hannon

Gubernatorial candidate Kathleen Blanco talks with her campaign manager Rochelle Michaud Dugas before the November 10, 2003, debate with opponent Bobby Jindal.

Oral history and additional research conducted by Mitch Rabalais.

This article is part of the “Democracy and the Informed Citizen” initiative, administered by the Federation of State Humanities Councils. The initiative seeks to deepen the public’s knowledge and appreciation of the vital connections between democracy, the humanities, journalism, and an informed citizenry. The Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities thanks The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for their generous support of this initiative and the Pulitzer Prizes for their partnership.

The spirit of the Christmas season was nearing its peak in 1997 when the life of Kathleen Babineaux Blanco’s youngest son, Ben, was unexpectedly and instantly taken in a workplace accident, by an industrial crane in free fall. His older brother, Ray, was standing close enough in the scrapyard to witness the precise moment his family’s history was grimly and irreversibly altered. As she collided with every parent’s nightmare and grasped for coping mechanisms, Blanco was concluding her second calendar year as Louisiana’s first female lieutenant governor, just a single step outside the succession line for the state’s most powerful elected post.“A lot of families break up over the loss of a child because of the grieving process,” Blanco said during a recorded oral history that was captured from her Lafayette home in August 2018. “Grieving being so difficult for everyone, and each handling it individually, it can be tough.” Her husband, Coach Raymond Blanco, a well-known and celebrated gridiron practitioner from Iberia Parish, found himself so overwhelmed by hopelessness in the wake of his son’s death that he briefly “contemplated walking into traffic and making it look like an accident,” according to a 2004 Gambit story. For her part, Blanco worked not to lose sight of the loving family God left behind, and to find “greater purpose in life”—but acknowledged there were no positives to glean from a son’s death—“only negatives.”

Ultimately, Blanco concluded, the past was what it was, but it was not the appropriate direction. She forced everyone to lean forward instead, and refused to let her family crumble to pieces. That harsh reality settled in during the funeral Mass held for Ben at Our Lady of Fatima Catholic Church, where a grieving mother was determined to issue a farewell on her own terms. With Ben’s coffin permanently shuttered, the lieutenant governor managed to deliver a heartfelt eulogy with grace and incredible composure, astonishing even those closest to her.

According to a sprinkling of the politicos who were and still are woven into Southwest Louisiana’s sugarcane fields, dance halls, voting booths, and bayous, this was when Kathleen Babineaux Blanco took her place alongside the giants of Acadiana.

Blanco celebrates her victory on November 15, 2003, becoming Louisiana’s first female governor. At her left is her husbad, Ray Blanco. Baton Rouge Advocate / Arthur D. Lauck.

Her meteoric rise in the male-dominated arena of Louisiana politics—Blanco also held the distinction of being the first woman from the Lafayette region elected to the state House of Representatives, and the first ever to ascend to the Public Service Commission, and subsequently its chairmanship—had been unexpected. There was little in the lieutenant governor’s early background that pointed to the makings of a leader. That included her roots in the French-speaking hamlet of Coteau, where a young girl with “no political ambitions” was born to a carpet cleaner. She took an early interest in the teaching profession, followed that dream through college, and had happily spent another decade and a half as a football coach’s wife and stay-at-home mother. She wasn’t as polished as former Governor Edwin Edwards, or as pragmatic as former US Senator John Breaux, and she didn’t have the guile of the late kingmaker Dudley LeBlanc. But this daughter of Iberia Parish did embody what it meant for a politician to have heart and courage.

She was rough around the edges, often fumbling for words, even during rehearsed speeches. All of which was just fine as far as voters and friends were concerned. Because there was but one Kathleen, and what you saw was what you got. And what you got somehow always rang familiar and bordered on intimate. From hugs and kisses on the cheek to the occasional well-placed curse word, from shooting ducks to displaying each and every ounce of available emotion for the world to see, Blanco was an unapologetic Southern woman.

And her story was far from over.

The winds of history and the passage of time would eventually elevate her status to that of a mid-level American governor succumbing to the limitations of her storied office. Under the harsh glare of an international spotlight, the woman described by the Washington Post as a “soothing Cajun grandmother” would also inexplicably become the target of a vengeful White House, marking the beginning of a premature end for her career in elected office.

Another six years passed before Lieutenant Governor Blanco spoke publicly again of Ben’s earthly exit—and it was certainly not by choice. The moment arrived in November 2003, during the final runoff debate for Louisiana’s gubernatorial election, which pitted Blanco’s pearl-clad, country-raised, long-shot Democratic bid against the wunderkind brand of Piyush “Bobby” Jindal. A first-generation Indian American, Jindal’s turnkey GOP campaign included endorsements from the sitting president and Bayou State governor, plus ample financial resources. There was national interest in his conservative shooting star, and the previous televised forum was broadcast live by C-SPAN.As the candidates and moderator inched toward the softball section of that final debate, with the cameras rolling and studio lights shining for a statewide audience, the lieutenant governor knew what was coming. “And I kind of knew what my answer would be,” she said in later reflection. “But I could never actually put words, or wrap words, around it. I never knew what I was going to actually say.”

It might not be a question about Ben specifically, but the name-a-defining-moment query was a guarantee, Coach and Kathleen Blanco had learned as students and practitioners of Louisiana politics. The duo had been running a consulting and polling firm—a hobby and source of additional income—since the 1980s. “If you actually do the polling and listen to some of the calls, you get to know what people think. We asked open-ended questions, and let them tell us their responses,” Blanco said in August 2018. “So they weren’t canned questions; they were open-ended questions. We weren’t pushing people in any direction. We wanted to know what they were really thinking. When I ran for office, at each stage, we quit polling. We picked it back up after I retired from the governorship, did a few more polls, and still occasionally do them.”

She got the message in terms of what people were really thinking in other ways too, such as when, in the decade after all of her children were in school, she attempted to find work outside of the home. She sought employment at a local State Farm agency. “I’m just uncomfortable hiring a married lady with children,” the unidentified insurance agent told Blanco. “Look, this kinda job is gonna put too much stress on your little family. And, heaven forbid,” he added, throwing his hands up, “I don’t wanna be responsible should you get a divorce.” (Blanco noted that she later “took great pleasure as governor of telling that whole story to the national head of State Farm.”)

All such insults, and a few attaboys—her life’s disappointments and rewards, and their accompanying grief and joy—had brought her to this moment, in November 2003, standing beneath the artificial lighting of a New Orleans studio. With a real-time link via live broadcast to Louisiana’s voters, Lieutenant Governor Blanco and Bobby Jindal were asked to share a revealing, personal moment.

Responding first, Jindal recounted the birth of his oldest child, but focused largely on his conversion from Hinduism to Catholicism—“when Christ found me.” As he continued, the lieutenant governor’s internal gears were churning. She tried to picture happier moments, and she wanted to avoid explaining what happened to Ben, but there was no use.

“It has certainly changed my life,” Jindal added, looking stone-faced at the camera with the red light. “It has changed me as a man, and the father I’ve tried to be.”

When Blanco came into frame to deliver her reply, there was brief pause before any words were spoken. The gap didn’t register audibly, but visually, it revealed everything. Her eyes and demeanor, even the shape of her mouth and tilt of her head, suddenly exposed misery, sleepless nights, and a primal ache that would never cease. “In the studio, it was a very dramatic moment,” WAFB-TV anchor George Sells told The Associated Press. In some respects, it was Ben’s eulogy all over again. She had to keep it together when keeping it together was seemingly impossible.

Or did she? Basic humanity was becoming a rare commodity in Louisiana politics, Blanco believed, and there was nothing left to give to the election but herself. During that brief, blink-of-an-eye pause, she made her final decision to be vulnerable in a profession that requires thick skin. While some of her female contemporaries chose to chew nails, kick shins, and live hard as a means of going along to get along, to prove they could even though they weren’t men, Lieutenant Governor Blanco was about to deny such personal barriers, pivot openly to her instincts, and let it all fly, consequences be damned, precisely because she was a woman.

“The most defining moment in my life,” said a televised Blanco, already choking back tears, “came when I lost a child.”

That echo-worthy sentence entered the Bayou State’s electoral ether with a splash. Republicans immediately resented her emotional appeal, but sympathized nonetheless. Democrats dried their eyes, then relished how that singular statement made her opponent’s response look slightly robotic. Reporters endeavored to write as quickly as she spoke, knowing their competition would have this angle placed high in their copy.

“Those are the moments,” the lieutenant governor continued, “when you have to really, really know that you have faith, and faith can bring you where you have to go. . . . That’s what makes me what I am today, knowing that one of the worst things that could happen to a person happened to me, and we were able to protect our family, and the rest of my children are stronger because of it.”

Voters soon dispensed with the runoff, prompting author and LaPolitics.com founder John Maginnis to offer his two-sentence synopsis on the November 15, 2003, election to National Journal. “Jindal ran a perfect campaign for five weeks,” said Maginnis. “But it’s a six-week campaign.”

Offering her own analysis, then Governor-elect Blanco told The Associated Press, “I’ve always felt or found in a big campaign, people eventually look for humanity.”

Two months later, on January 12, 2004, while standing on the steps of the limestone tower designed during the Huey P. Long administration, Kathleen Babineaux Blanco took the oath of office that was reserved for Louisiana’s fifty-fourth governor. As quickly as she could, she looked down from her perch on the temporary stage and saw her high school classmates from Mount Carmel Academy in Iberia Parish. Like her, they were beaming.

“A bunch of women, my age, you know,” Blanco said during the oral history that was recorded for this project. “There was so many mothers and fathers with their daughters. They had little boys, too. But I think that people made an extra effort to bring their young daughters and their little girls, you know, like eight and nine years old, dancing with excitement. They were so excited! And it was really . . .”

She paused. “I don’t always stop and feel a historic moment, but I did feel this historic moment. And I wanted all of those women, young, middle-aged, older women to just be so proud, and that’s what I felt back from them. There was that huge sense of pride that one of us had been able to crack the proverbial glass.”

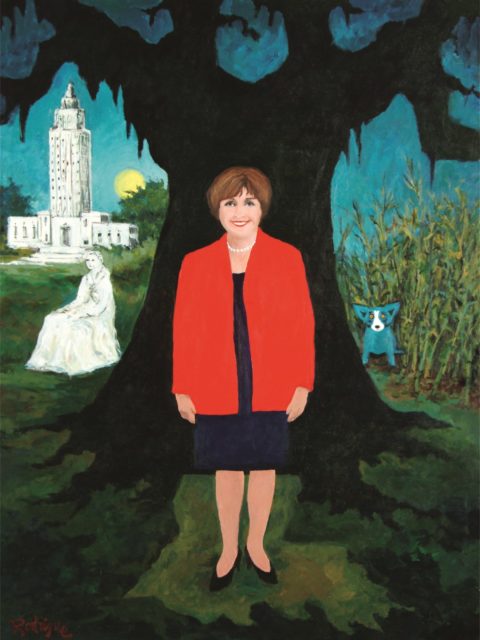

Known as a Cajun Casanova around the Capitol, state Representative Troy Hebert of Jeanerette had finally encountered a woman he couldn’t charm. Only a few months in office, Governor Blanco was urging the legislature to embrace revenue-raising measures. As a member of the leadership, Hebert was expected to fall in line. But the fun-loving country chairman of the House Insurance Committee voted against a critical tax package—and he lost his gavel as a result. Standing on the same Capitol steps where the governor was sworn in, Representative Hebert preached from a fiery press conference about the “dictatorships” that had taken root in Louisiana for far too long. “The one thing that has changed is that we’re no longer being ruled by the Kingfish,” Hebert told the assembled reporters. “We’re being ruled by the Queen Bee . . . History may not remember me, but it’ll remember the Queen Bee.”Governor Blanco got a good laugh out of his classical display of political oratory. In fact, her entire administration took to the title like bees to honey. Original works of art, lapel pins, and even candy surfaced to honor the Honorable Lady’s trademark sting. Per the ancient traditions of Capitoland, Representative Hebert and Governor Blanco were also friends again in no time. If anything, she owed the so-called “champion of the little man” a debt of gratitude. Between that swift injection of flex in the House and her team’s handling of the Bobby Jindal Machine, the Blanco brand was taking on a tougher demeanor. While her emotional confession during the final televised debate was often credited for her victory, given how memorable it was, Governor Blanco and her inner circle believed her campaign’s decision to go negative against Jindal—including hard-hitting contrast ads produced for television by media consult Ray Teddlie—was what truly turned the tide. Her public perception may have been one of a kindly and stern grandmother, but the political reality was closer to a poker-playing grandmother, a down-home grinder who was willing to bluff, go all in, or slow-play—whatever it took.

“The one thing that has changed is that we’re no longer being ruled by the Kingfish,” Hebert told the assembled reporters. “We’re being ruled by the Queen Bee . . . History may not remember me, but it’ll remember the Queen Bee.”

Alas, everything—as in everything—changed in most of Louisiana on August 29, 2005. What rolled ashore in the southern reaches of Plaquemines Parish had brought with it an end to Governor Blanco’s elected career, although she didn’t know it yet. The Atlantic event could have been named José had it formed just a touch earlier, but Katrina it was. A devastating Category 5 hurricane, Katrina left an apocalyptic path of destruction in her wake. Coastal communities were decimated, floodwaters reached second-story windows in Chalmette, and a levee breach in New Orleans filled the bowl-shaped city with terror as residents died or became trapped.

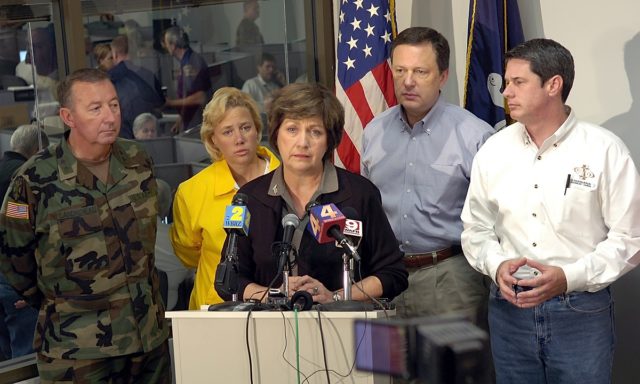

Governor Blanco boarded a helicopter in Baton Rouge the next morning to fly over the impacted areas and assess the situation for herself. After viewing the damage and briefly touching down at the Superdome to meet with what the cable networks were calling “refugees,” the governor returned to the Capital City. With the eyes of the nation on her state, she addressed the assembled media in a small briefing room in the state’s emergency operations center. For most Americans outside Louisiana, this was their first introduction to Governor Blanco.

In the haze of the tragedy, she offered a somewhat dizzy summary for reporters before locking eyes with Ed Anderson, a grizzled veteran at the Times-Picayune. Without warning, he quietly started to weep, which touched the governor deeply. She knew Ed and his wife, and she was aware of their profound connections to the Crescent City. The intimacy of the moment and her history with Ed overtook Governor Blanco. Her voice cracked and her eyes brimmed with tears. It was an otherwise tender experience shared between two people, but America’s working press corps was watching as well. After trying to restart her presentation, the governor’s voice trailed off again as she stared at the podium, presumably attempting to regain her composure. Then US Senator Mary Landrieu, standing nearby with other officials, moved in and patted Governor Blanco on the back in a sympathetic manner.

Gov. Blanco at a press conference on August 30, 2005, the day after the levees failed in New Orleans. She is flanked by Louisiana National Guard Major General Bennett Landreneau, US Sen. Mary Landrieu, D-LA, FEMA director Mike Brown, and US Sen. David Vitter, R-LA.

Baton Rouge Advocate / Bill Feig

The following day, the governor was in between interviews with network affiliates when her press secretary approached her to privately discuss an issue. While not live, the microphones were hot and the cameras were rolling. The governor became emotional, tearing up as their discussion progressed. To the Blanco administration’s dismay, CNN obtained the footage from satellite feeds and the private exchange became public. Editorial writers and armchair politicos tagged Governor Blanco as overwhelmed and out of her league. “If you can’t cry when so much has been lost,” she thought to herself, “when do you cry?”

Michael Brown, who served as the director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, would later tell historian Douglas Brinkley, “I just see Blanco as this really nice woman who is just way beyond her level of ability.”

White House Chief of Staff Andy Card was running late, and Governor Blanco was furious. A couple months had passed since her public image went sideways. Since then, a predictable game of pointed fingers had commenced. Voices in state government cited problems with the federal response, while sources close to President George W. Bush pushed stories to reporters about gubernatorial mismanagement. Sitting in the West Wing, awaiting Card, Governor Blanco realized she was on enemy turf; and for their part, they surely thought an intruder was in their midst.When she was finally let into the chief of staff’s office, Card was dismissive, noting that her ten-minute courtesy visit was ticking away. Governor Blanco gave him a look that her children would have instantly recognized—and feared.

“You’ve never heard me say a word against the president of the United States during this whole turmoil,” she exploded. “But you put your dogs on me and tried to undermine what I was doing.”

Card stammered. Governor Blanco cut him off.

“And Karl Rove put out a lie on me about the disaster declaration,” she said, referring to the president’s senior advisor. “You’re misinterpreting nice for weakness. The only thing is, I’ve been watching you all. What you do understand is war. So I’m declaring war on the White House!”

If the White House continued its assault, she vowed, her administration would refuse to sign off on oil and gas drilling permits. Production in the Gulf of Mexico would grind to a halt, she warned the president’s chief of staff. Her team would also start hitting back in the mainstream media, she added. The threats panicked Card, she later recalled, which was enough of a win that day. As the governor left the White House, the aide who had accompanied her finally spoke up.

“You realize you threatened the president of the United States, right?”

Blanco nodded without a degree of emotion. She was eager to return home, where voters would soon learn of—but not be surprised by—her decision to forgo a re-election campaign. And she just couldn’t wait to see Coach. He was going to love this story.

Did she just threaten the president?

“I did,” Governor Blanco said while staring down the aide and making her own political exit. “Not once, but twice!”

Jeremy Alford is the editor and publisher of the LaPolitics.com suite of political publications and the co-author of Long Shot, which recounts the Bayou State’s 2015 race for governor. His byline has also appeared in the New York Times, Dallas Morning News, and Campaigns & Elections magazine. Jeremy lives in Baton Rouge with his wife, Karron, and children, Zoe and Keaton. His next book, on Louisiana’s 1973 constitutional convention, is due out this winter.