Magazine

The “Tuba Fats” Riff

Anchored by the simple tuba part, melody after melody unfurls out of the trumpets, trombones, and saxophones. On the street, “Tuba Fats” can last for blocks.

Published: August 30, 2018

Last Updated: February 20, 2023

Michael P. Smith

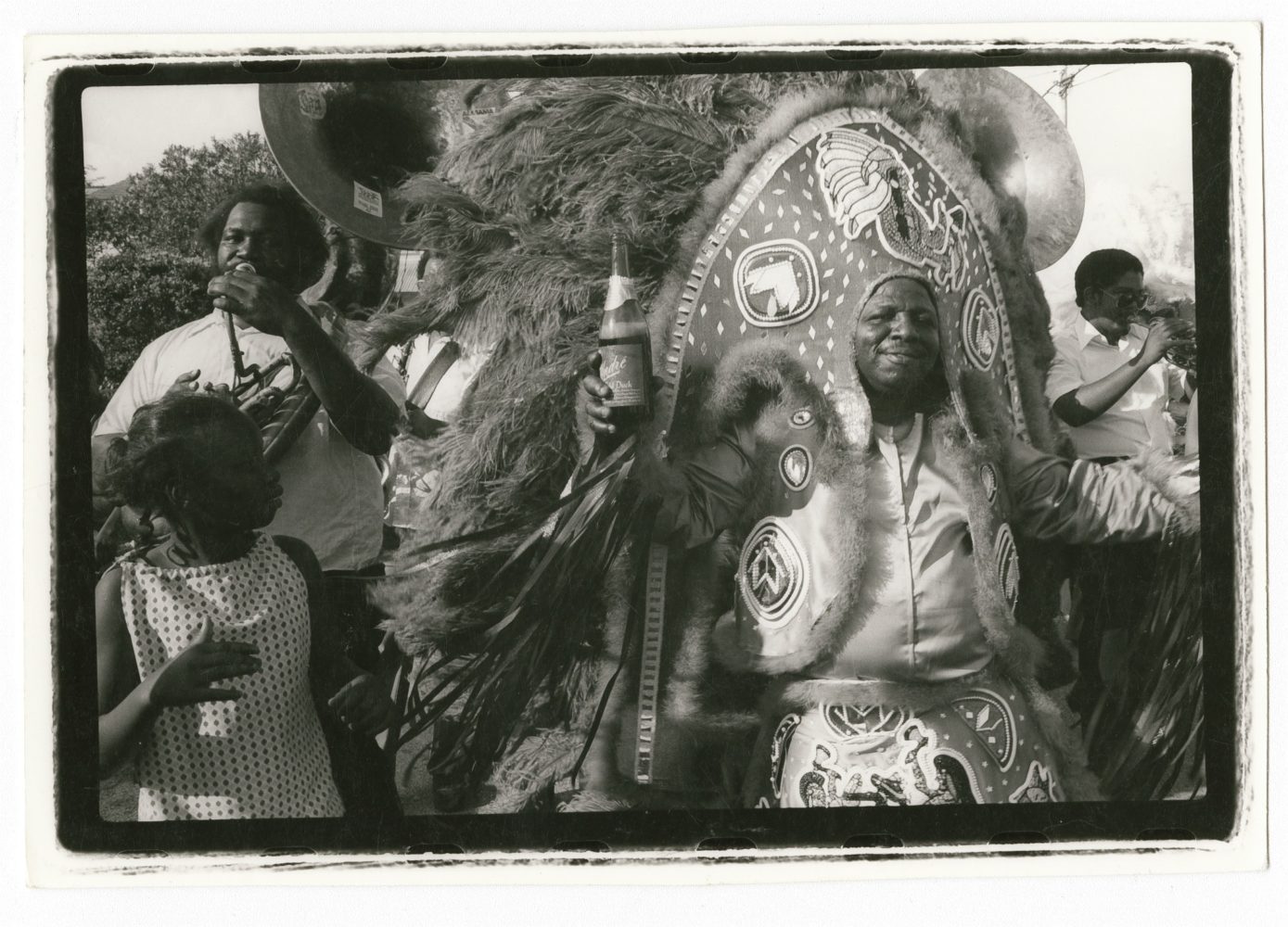

Anthony "Tuba Fats" Lacen with Mardi Gras Indians in Marrero, Louisiana, 1978. (The Historic New Orleans Collection ACC.NO.2007.0103.4.133)

Lacen, who died in 2004, was a key player in launching what came to be known as a brass band renaissance in the 1970s. For a century, black New Orleanians had cultivated the stodgy marching band into a moving jazz ensemble, with a front line of trumpets, trombones, and saxophone creating an improvised melodic blend, and a back row of tuba and drums providing syncopated parade rhythms. Tuba Fats and Kirk Joseph from the mighty Dirty Dozen Brass Band challenged tradition by funkifying the brass band, transposing bass riffs from James Brown, Parliament, and Earth, Wind & Fire onto the tuba. While trumpeters from Louis Armstrong to Milton Batiste had once ruled brass band territory, today the back row has taken center stage, and the generation of post-1980s brass bands, including Rebirth, the Hot 8, and the Stooges, are now led by tuba players.

To locals, “Tuba Fats” refers to both Lacen’s fat-bottomed, booming tuba melody as well the song built around that riff. Either way, those handful of notes makes “Tuba Fats” instantly identifiable in the streets, an impressive feat considering it’s never had a definitive recorded version. We can be certain Lacen appears on one recording himself, on a medley of “Mardi Gras in New Orleans and Tuba Fats,” from the little-known late ‘70s album, Serenaders by the Olympia Brass Band. Halfway through this 15-minute monster, which begins as a cover of the Professor Longhair classic “Mardi Gras in New Orleans,” Tuba Fats signals the transition by announcing his trance-like riff, powering a full seven minutes of bouncing brass. The other version of “Tuba Fats” is even more obscure: recorded on a 45 single by Floyd “Flo” Anckle and the Majestic Brass Band. It’s unclear if Lacen himself played on it, but it is unmistakably the Tuba Fats riff that opens the song. Both recordings sound glorious, we can tell you, but until recently, neither version was readily found online.

And yet “Tuba Fats” continues to be played on Sunday afternoons at pretty much every second-line parade, by all the different brass bands, in every corner of the city. Its ubiquity through oral transmission is all the more surprising considering how complex it is. Anchored by the simple tuba part, melody after melody unfurls out of the trumpets, trombones, and saxophones. On the street, “Tuba Fats” can last for blocks, and none of the early recordings include all the phrases found in contemporary performances of it (the version on the Rebirth Brass Band’s 2006 Rebirth for Life album comes closest to capturing the song in its full glory).

The discerning listener will notice that on some versions of “Tuba Fats” there’s another New Orleans street classic buried within – “Hey Pocky Way.” The original source material comes out of the Mardi Gras Indian tradition of African Americans honoring Native Americans in elaborate rituals of masking and music. “Tuway Pockyway” is one of the oldest documented chants, sung in call-and-response by the chief and his tribe, with tambourines and other hand percussion providing the only accompaniment. It was The Meters that relocated the song, as “Hey Pocky A-Way,” from the backstreets into national prominence on their 1974 album Rejuvenation. With the melody rearranged for an electrified funk band and the lyrics rewritten as an ode to “feel-good music,” “Hey Pocky Way” has been adopted as a regional anthem for a city where Mardi Gras Indians and brass bands, funkers and rappers, all drink from the same well.

As Lacen recounted for historian Mick Burns in Keeping the Beat on the Street (2006), “We were doing a parade, and when the band stopped, the second liners, with tambourines and stuff, started singing ‘Hey Pocky Way.’ So I started putting a bass part to it.” While Lacen’s inaugural recording with the Olympia was listed as “Tuba Fats,” the Majestic 45 was released as “Hey Pocky Way.” The Majestic’s co-leader, tuba player Edgar “Sarge” Smith, recounts in Burns’ book, “We heard things like the Olympia playing ‘Hey Pocky Way.’ They were the first brass band to do it; they called it ‘Tuba Fats.’”

This era in the city’s brass band tradition marked a crossroads between traditionalists and the musicians who wanted to embrace rock n’ roll and soul/funk styles. Kenneth “Little Milton” Terry, a trumpeter with the Junior Olympia Brass Band, remembers a time when the group was playing “Tuba Fats” in their practice room and Olympia’s Milton Batiste overheard them: “Milton went into a rage. He told us, ‘Don’t you ever come back here playing that shit! Whatever you do, I want you to stick to the tradition.” Today, both the composer and his namesake song are celebrated as a link between the old-school approach that Batiste was teaching his disciples and new-school transformations taken up by riff-masters like “Tuba” Phil Frazier of the Rebirth and Bennie “Big Tuba” Pete of the Hot 8. In a jazz funeral, “Tuba Fats” is the go-to piece to bridge the traditional dirges and upbeat spirituals like “I’ll Fly Away” with the more contemporary tunes of the hip-hop generation, like Rebirth’s “Do Whatcha Wanna.” Because, as Gregory D and Mannie Fresh knew with “Buck Jump Time,” there’s no better way to get New Orleans locals off their feet than to pump things up using one of city’s best-known b(r)ass lines.

After Lacen passed in 2004, it spurred an outpouring of homages from various brass bands. Critical Brass, formed in New Orleans but now based in Los Angeles, recorded “That Camel and Tuba Fats” in 2004. Over the next couple years, the Rebirth and Treme Brass Bands would each record their own versions. Perhaps most unexpected is a 2016 performance of “Tuba Fats” by the Coventry High School Band of Coventry, CT, which was recorded live and made available on YouTube. The band’s musical director, Ned Smith, introduces the performance by describing “Tuba Fats” as “a very very traditional New Orleans second-line tune.” Such a proclamation may very well have chafed Milton Batiste, but perhaps Lacen would have been pleased to know that his forty-year-old creation stuck around long enough to become a modern-day second-line classic.

Matt Sakakeeny is Associate Professor of Music at Tulane University and has lived in New Orleans since 1997. He is the author of Roll With It: Brass Bands in the Streets of New Orleans and editor of Remaking New Orleans: Beyond Exceptionalism and Authenticity. Matt is a board member for Roots of Music and the Dinerral Shavers Educational Fund, and he has received a grant from the Spencer Foundation for his next book on marching band education in the New Orleans school system.

Oliver Wang is a professor of sociology at California State University–Long Beach and the author of Legions of Boom: Filipino American Mobile DJ Crews of the San Francisco Bay Area. He contributes to NPR’s All Things Considered, KCET’s Artbound, KPCC’s Take Two, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and other outlets. He is the creator and writer of the audioblog Soul-Sides.com and the producer and co-host of the album podcast Heat Rocks.