The Walls

Louisiana’s first state prison survives in archival images

Published: December 1, 2019

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

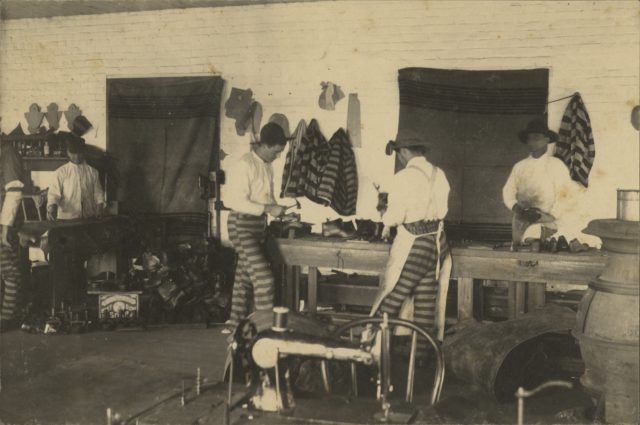

The images here date to around 1900 and are from the Henry L. Fuqua, Jr. Lytle Photograph Collection and Papers, which comprises 19th- and early-20th-century images of Louisiana and especially Baton Rouge taken by photographer Andrew D. Lytle. The collection is held in the Special Collections at Louisiana State University Library. Above, men work in the clothing factory.

In his January 3, 1832, address to the General Assembly, Louisiana Governor André Roman stressed the need for a “house of correction” that would save the $20,000 per year spent to house state prisoners and remove them from the fetid, vermin-infested New Orleans jail where they had been housed. The legislators agreed to an initial appropriation of $50,000 the following year, which eventually grew to a $73,000 outlay even before the first state penitentiary opened three years later in 1835. Known as the Walls for its towering brick enclosure, the facility’s first building was constructed on the corner of St. Anthony (now Seventh) and Laurel Streets in Baton Rouge. The complex eventually expanded to the property bounded by Florida, Laurel, Seventh, and Twelfth Streets, where the Russell B. Long Federal Building and United States Courthouse now stands, underlying the edge of today’s downtown Baton Rouge. Thousands of prisoners—male and female, adults and children, black and white, free and enslaved—stayed in or at least passed through the Walls from 1835 until it closed in 1917.In the antebellum period, almost one-third of Louisiana’s prison population was enslaved; about five percent were women. White female prisoners, many of whom were Irish immigrants, came and went, while black women, subject to harsher sentencing, often came to stay. The laws governing enslaved and free people of color in Louisiana included more crimes and harsher sentencing for the enslaved, with execution as the mandated punishment for many crimes. Mothers brought children with them. Other women were pregnant when they arrived or became pregnant during their incarceration; their babies lived at the penitentiary. Under a law specific to the penitentiary, children born of enslaved mothers during their incarceration were state property. Between 1849 and 1861 the state sold at least eleven of them away from their mothers.

Before the Civil War, convicts ate and slept in individual, seven-by-four-foot cells, with a 12-inch square grated opening in the solid iron door. They walked lockstep, chained at the ankles, everywhere they went outside the cells. The men initially worked at individual crafts and later at mechanical and factory operations, work intended to create a revenue stream for the state (or at least make the prison self-sustaining) and keep prisoner-made crafts from competing with local businesses. The women washed, sewed, and mended. Silence was pervasive and enforced. In 1844, having failed to turn a profit from its prisoners, the state leased the penitentiary and its incarcerated population to the first in a series of private lessors who worked the prisoners until 1901, when the state reclaimed control. In 1862, during the federal occupation of Baton Rouge, a musket ball flew over the walls and landed in the penitentiary yard, prompting officials to transfer the prisoners to New Orleans, first to the workhouse, then to the abhorrent Orleans Parish Prison, where they remained until February 1866.

The Walls had barely reopened after wartime disruptions when the state signed an initial lease with retired Confederate Major Samuel L. James, which remained in place for the next 21 years; James leased out the convict labor and returned a portion of the profits to the state. Subleasing prisoners to work on levees and railroads as well as to plantations (including Angola) that had formerly been worked by enslaved laborers made James much more money than any factory operation at the Walls. Soon the Baton Rouge facility became more of a receiving/processing station. Only prisoners unable to work, the seriously ill, and those deemed escape risks remained at the penitentiary, and few women were found at the post-war Walls.

In 1901 the lease with James’s heirs ended, and the state resumed control of its prisoners as part of a general trend away from convict leasing across the South. In one last effort to make money at the Walls, the state built a new and modern shoe and clothing factory for inmates to work in. The state also transferred executions to the Walls from 1910 to 1917, building gallows that ultimately took the lives of thirty-five men who “embraced religion and walked with a steady step to their death,” according to Chaplain Henry Johns. Finally, the city of Baton Rouge, preferring not to have a penitentiary downtown, purchased the “grim brick walls” from the state for $45,000, ultimately demolishing the structure to make way for new development.

Inmates produced bread at the Walls. The penitentiary’s 1834 bylaws required that each prisoner receive one pound of either wheat or corn bread daily. Various accounts of the meals over the years give widely disparate descriptions of the food, especially the bread. Some days the bread could be mush (and molasses) wheeled into the kitchen in a wheelbarrow and ladled out into the convicts’ bowls with a dipper. Others it could be dark-colored, but light and spongy—good, healthy bread fresh from the Walls’ ovens, as it was described in the 1870s. Initially the bread accompanied meals consumed in solitary silence, with each prisoner supping alone in his or her cell. Later, convicts ate together, still in silence, at numbered places around communal tables, segregated by race and sentence, with lifers in the middle.

When the state resumed control of prisoners in 1901, administrators immediately restarted the shoe and clothing factory at the Baton Rouge facility. Male inmates made and wore the products; female prisoners never touched the sewing machines, though they did wear discharge outfits made by their male counterparts. Prison coats, summer and winter pants, nightshirts, drawers, cooks’ hats, shoes, discharge clothing, and various bedding and linens were all produced during the factory’s first year. By 1914–1915, the penitentiary’s board reported that approximately 100 men at the Walls produced enough clothing, bedding, and shoes to supply the average penitentiary population of 2,046 convicts.

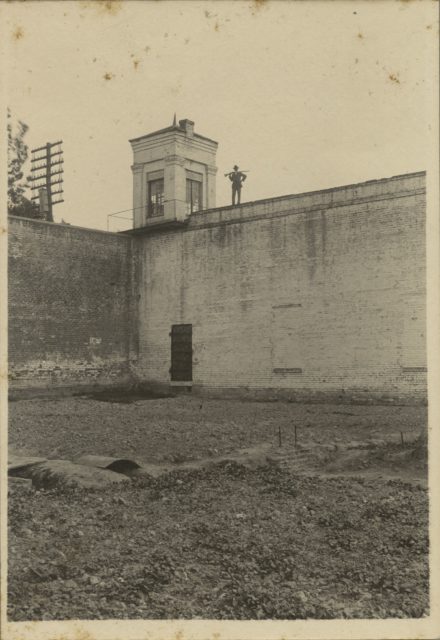

Guard towers, armed guards, and a brick wall enclosing the Baton Rouge penitentiary were designed to provide security, subject convicts to constant surveillance, prevent escapes, and symbolically represent a barrier between what society deemed the good and the bad. The outer walls rose more than three stories to form a giant hollow square. Their foundations sank three to five feet below ground and were five feet thick at the base, gradually decreasing to 26 inches just below the surface level. This depth and thickness presumably created a virtually impenetrable barrier to the outside world. The brick sentinel box added to the wall’s height and imposing facade. The guards, well-armed with muskets, pistols, and swords even inside the prison, should have provided the last barrier, but men and women alike sometimes found their way out.

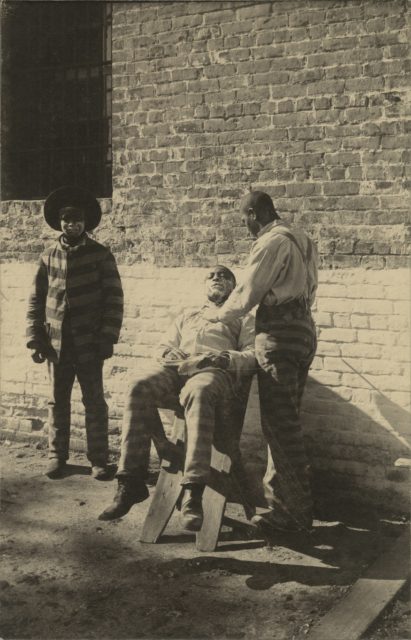

Even before the penitentiary opened, rules and regulations adopted in 1834 dictated personal hygiene requirements. Each male convict received a uniform and was required to have his hair cut and his face shaved. Twice a week a convict barber shaved the inmates. Once in the late 1890s, when the regular convict barber was not available, authorities asked a repeat offender to pitch in, to the consternation of the men in line. He only shaved one person, who left the chair bloody.

Male prisoners at the Walls made shoes almost from the day the gates opened until the facility closed in 1917. A journalist visiting in the 1840s found Dr. David Hines, an infamous New Orleans dandy and con artist and a prolific escapee, making hand-crafted red brogans, a type of work shoe. Within months of the prisoners’ return to the penitentiary after the Civil War, twenty men were producing hand-made shoes promised to outlast two pairs of shoes made in northern factories and workshops. Eventually using the most advanced electrical machinery available, shoemaking at the Walls became a major factory operation, producing shoes both for state use and the open market.

Marianne Fisher-Giorlando is Professor of Criminal Justice Emerita, Grambling State University. She has been a member of the Angola Museum Board since 1998 and is the outside researcher for the Angolite. Dr. Fisher-Giorlando researches the history of women in the Louisiana State Penitentiary from before the Civil War to 1961.