This is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things

The ongoing battle between historic preservationists and trespassers

Published: February 28, 2025

Last Updated: May 30, 2025

Photo by Brian M. Davis

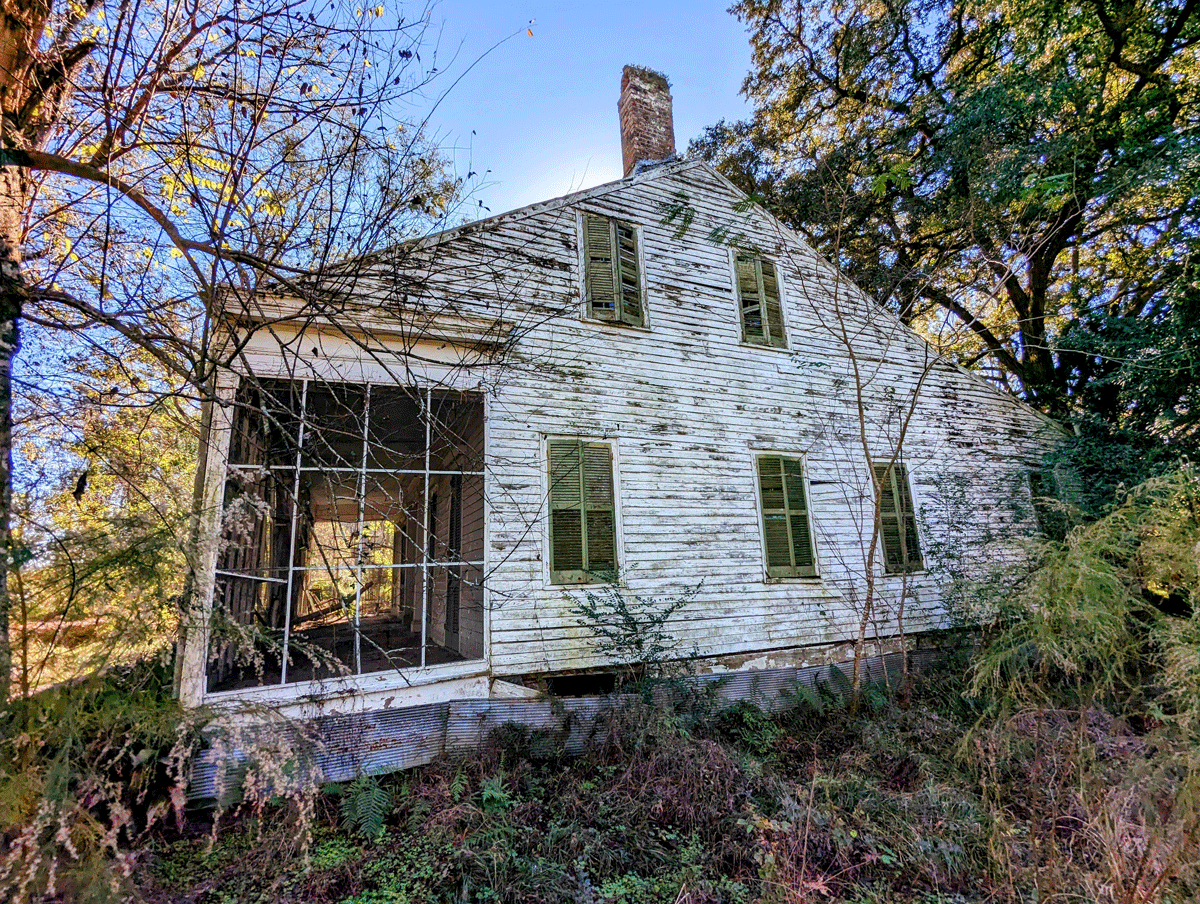

The side view of a Greek Revival house included in a viral social media post which provided thieves with the location and list of items to steal, ultimately leading to the home’s demolition.

To those who work in the field of cultural resources, it is a great honor and responsibility to be stewards of the past, through both narratives and artifacts. Over the past twenty years, technological advancements have greatly increased our research capabilities through improved access to historic documents, manuscripts, maps, and images. We are able to digitally search through online archives and libraries halfway across the globe and translate languages we do not speak. We are also able to question sources of narratives written a century ago, and test theories of what really may have happened. As the Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe noted in a 1994 interview with the Paris Review, “There is that great proverb—until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.” The leading historical account of an event or people is always told by those who held more power, influence and resources; archaeology, historic preservation, archival research, and materials conservation help us more fully understand an event as it may have occurred rather than as the dominant narrative of the day presented it.

Technological advancements over the past two decades have also brought about new threats to cultural resources. Social media makes it easy to widely share photos and information about historic sites. While many people may appreciate the beauty of an “abandoned” historic building and its interaction with nature or thoughts of what lives must have played out in the space, others react to these posts as an opportunity to steal.

Author David Lowenthal writes in The Past is a Foreign Country, “Possession of valued relics enhances life. To have a piece of tangible history links one with its original maker and with intervening owners, augmenting one’s own worth.” It is natural for us to feel awe when viewing an object or site from a distant land or time, and to contemplate how it was used or what it has experienced. This drive to collect and possess history fuels the illicit trafficking of artifacts from around the world. Some questions to consider before acquiring a cultural item: Is it ethical to own the item? Can you properly care for it? Could public or scholarly access to it foster a better understanding of the culture it represents?

In the fall of 2022, a developer contacted the Louisiana Trust for Historic Preservation about a property he recently purchased in East Baton Rouge Parish. The plan was to redevelop the land for a new housing complex. An existing house from the first half of the nineteenth century would not be retained on site. We began working with a team to locate someone with an adequate receiving lot and sufficient funds to relocate and rehabilitate the building. After visiting the site to assess the logistics of moving such a large structure, the team spoke with several interested parties. One potential owner was getting final pricing for the preservation project; everything appeared to be lining up for a move that summer, ahead of the proposed new construction on the original site.

The elaborate front entrance to an early nineteenth century house shared on social media as “abandoned.” After thieves stole the original millwork, all interest in rehabilitating the house dissolved. Photo by Brian M. Davis

As the screen of vegetation separating the house and outbuildings was cleared, social media posts about the site went viral. In the pre-dawn hours of Mother’s Day, a neighbor’s security camera captured footage of a crew stealing the original doors, mantels, and other architectural elements from the historic home. That was all it took to kill the preservation project, including the house. The potential owner was no longer interested; the cost of replicating the missing historic details, even out of modern materials, made the project that much more of a challenge. The thieves had picked the bones clean. Ultimately, the historic house was demolished.

For this reason, we are extremely careful about what information we share on social media about historic sites, especially those in remote locations or which may not be occupied continuously. An innocent post about an architectural wonder may be shared with someone who sees it as an opportunity to trespass and steal. Indeed, even public comments on photos like these range from general appreciation to “That would look good in my house!” Those who trespass in vacant properties and steal items often seem to feel that their actions are justified, as if they are saving them from an uncertain fate. This was the case recently when someone broke into a building under construction and decided to “save” the original Carrara marble screens used in the men’s restroom. Thus, in one night, a significant portion of the building’s historic fabric was destroyed.

While many people may appreciate the beauty of an “abandoned” historic building and its interaction with nature or thoughts of what lives must have played out in the space, others react to these posts as an opportunity to steal.

Social media posts about Native American sites can often lead to the destruction of the site, loss of cultural artifacts along with the knowledge they can tell us, and in some cases desecration of human burials. For example, someone will create a social media post about a particular prehistoric site. The post goes viral, information about the site’s location is shared, and soon afterwards, people begin arriving from locations near and far, even out of state, with the expectation of being able to dig and search for artifacts. “NO TRESPASSING” signs are posted, ripped down, replaced, ripped down again. Some social media groups pride themselves on the artifacts they excavate, whether they retain them for their own collection or traffic them for monetary gain. People will concoct opportunities for others to pay to participate in “digs,” complete with earthmoving equipment and screens. Photos and videos of their discoveries are shared with the group to fuel the thrill of the hunt, with no regard to the loss of knowledge or disturbance of burials that destruction of the site has caused.

In 1991, the Louisiana Legislature passed the Louisiana Unmarked Human Burial Sites Preservation Act to help protect unmarked burial sites from economic development as well as from those who mine for artifacts. This includes prehistoric and historic Native American, pioneer, and Civil War unmarked burials. The legislation declares it unlawful to disturb an unmarked burial site, human skeletal remains, or burial artifacts; to buy, sell, possess, display, or destroy human skeletal remains from an unmarked burial site or burial artifacts; or to allow access to or provide funding to someone for the purpose of disturbing an unmarked burial site, human skeletal remains, or burial artifacts. The legislation also provides direction for anyone who feels they have discovered an unmarked burial site, instructing them to cease activities which may further damage the site and contact local law enforcement officials.

Fired clay vessels and bowls from the Tunica Treasure, now on display at the Tunica-Biloxi Museum in Marksville. Photo by Brian M. Davis

In 1968, a twenty-six-year-old guard at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, armed with a metal detector and shovel, began searching for the site of a settlement used by the Tunica tribe from 1731 to 1764 during their period of trade with the French and other tribes. After discovering and looting the settlement, including 150 burials in its cemetery, his Avoyelles Parish home quickly filled with artifacts as he searched for a buyer. It was at this time that Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology began a survey of the Lower Mississippi River Valley and were invited by the guard to examine his loot. This group of burial offerings would collectively become known as the “Tunica Treasure.” An extended legal battle over ownership of the artifacts led to a landmark ruling that helped lay the groundwork for the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in 1990. A major provision of NAGPRA is that human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony shall be protected and returned to their respective Native American tribes. Numerous museums and institutions are working towards repatriation of remains and objects from their collections. The incident also helped furnish documentation of the ancient heritage of the Tunica peoples so they could gain state and federal recognition as a tribe. The artifacts were returned to the Tunica–Biloxi Tribe; they may be viewed at the Tunica–Biloxi Cultural and Educational Resources Center in Marksville, Louisiana.

The Louisiana Division of Archaeology maintains records of sites of cultural importance which are reviewed when permits for state or federal projects are planned. We will continue to find records of our past when fields are cultivated, when new sites are cleared for buildings or road expansion, and when storms uproot trees or erode the soil. The responsible action to take when you notice cultural resources is to reach out to professionals, to make them aware of the site, and if possible to do this even before a site is disturbed, as the context of an artifact or feature is extremely important to our understanding and interpretation of a site. One should never dig for artifacts, unless participating in an organized, professional excavation with groups like the Louisiana Archaeological Society or universities. With October celebrated as Archaeology Month, the Division of Archaeology hosts numerous opportunities for people to show their finds and have them identified. Never purchase or sell cultural artifacts, since that promotes the looting industry.

Architectural salvage is an important way to reduce the amount of reusable building materials in our landfills and provide a resource of comparable materials for those maintaining historic properties. The Louisiana Trust advocates for more non-profit organizations and municipalities to begin this type of operation, especially for historic buildings which cannot be feasibly rehabilitated and must be razed for code enforcement concerns. Communities can easily organize a system for collecting reusable building materials after a storm or fire, or just before a demolition, and offer them at a reasonable price to the general public and contractors. By maintaining limited hours and low overhead costs, the program can sustain itself and become an educational outlet for preservation topics. The best approach to maintain an ethical operation is to only take donated items and to refuse to purchase historic materials. This will help deter someone from stealing a mantel, columns, or doors from a vacant building hoping to sell them to a dealer for quick cash.

As for buildings, appreciate their design, materials, and stories of the people associated with them. Take photographs to enjoy yourself, but be careful about the vulnerability of the site when sharing or giving specific details about the building on social media. Those posts can quickly spread beyond your circle of friends. Do not trespass, for your safety and the safety of the building. Visitation to a vacant historic building should always be after gaining permission from the legal owner, who may be able to alert you to hazardous conditions. Ask them about plans for saving or selling the building to someone who may rehabilitate it. Never remove parts of a building—or anything else you see—without permission from the owner. How would you feel if someone dug up your deceased relatives or removed parts of your house for what amounted to a few dollars?

Brian M. Davis is executive director of the Louisiana Trust for Historic Preservation. Based on his family’s farm in Ouachita Parish, he connects the dots with preservation projects in all 64 parishes.