Fall 2024

Time Capsules on Canvas

The fight to preserve Louisiana artist legacies

Published: September 1, 2024

Last Updated: December 1, 2024

Estate of Tina Girouard, Artist Rights Society (ARS), NY

Photograph by Gerard E. Murrell, On the Cane Break: Portrait of Tina Girouard, 1976, Cecilia, Louisiana.

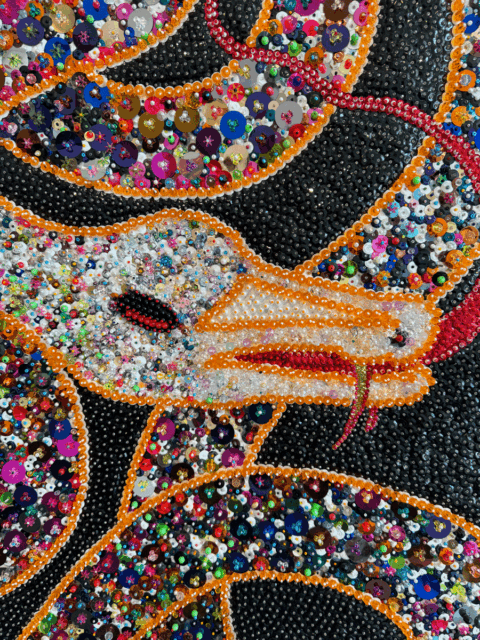

Tina Girouard, detail of Damballa, 1991–1992. Estate of Tina Girouard, Artist Rights Society (ARS) New York.

Editor’s Note:

When southwest Louisiana interdisciplinary artist Tina Girouard passed away in April 2020, she left behind nearly half a century’s worth of artworks of various mediums: textiles, digital files, sculptures, and photographs. Many of these pieces, which collectively represent Girouard’s extensive pioneering artistic legacy, would likely have been lost to time and the ravages of Louisiana humidity and heat in her home in Cecilia, were it not for the meticulous efforts of Girouard’s niece, Amy Bonwell. Here, Bonwell speaks to her efforts to save, document, digitize, and promote Girouard’s life’s work, which resulted in a posthumous retrospective exhibition curated by the Rivers Institute for Contemporary Art and Thought held at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art earlier this year.

Inspired by Bonwell and Girouard’s story, for the subsequent pages, 64 Parishes’ editorial staff turned to artists currently living and creating across Louisiana to ask them to share their thoughts about preserving their own artistic legacies: what methods they implement in their practices to document their work, why record keeping matters, and the way art can chronicle a cultural moment in time for future generations.

Most artists innovate in some fashion. They might have been agents of change, or have expanded art-making techniques, or contributed new ways of doing, thinking, seeing, feeling, sensing, knowing. This creates value for artist legacies.

Tina was a pioneer in performance, conceptual, and video art, and was well known for her pattern and decoration themes that elevated common materials such as wallpaper and decorative ceiling tin. She reinvented her artistic vocabulary multiple times and left a legacy that is linked to places where she presented work such as Lafayette, Port-au-Prince, Mexico City, Zagreb, and New York. I continue to advocate for Tina’s legacy by making the work available to curators and art institutions, recreating historic performance artworks, and especially maintaining ties with the sequin artists of Haiti whoTina championed in her book of the same name.

In thinking historically about artist legacies, I’m reminded of Jo van Gogh-Bonger, who championed the work of Vincent van Gogh. Jo was Vincent’s sister-in-law, married to Vincent’s brother and main art supporter, Theo, who died less than a year after Vincent’s passing in 1891. Jo was left a widow and single mom, yet she took on Vincent’s legacy, organizing numerous exhibitions, “getting it seen and appreciated as much as possible.” There are so many stories like this—the great novelist and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston’s papers were literally on fire when a friend happened by and put it out, preserving much of her legacy, including historic photos and original manuscripts.

These are dramatic examples but still, they illustrate the importance of caring for a body of work so that it can continue to inspire and become a record of our cultural heritage. Louisiana has so many creatives, culture bearers, and histories that could and should be preserved—fingers crossed!

— Amy Bonwell, Tina Girouard’s niece and executor of her estate

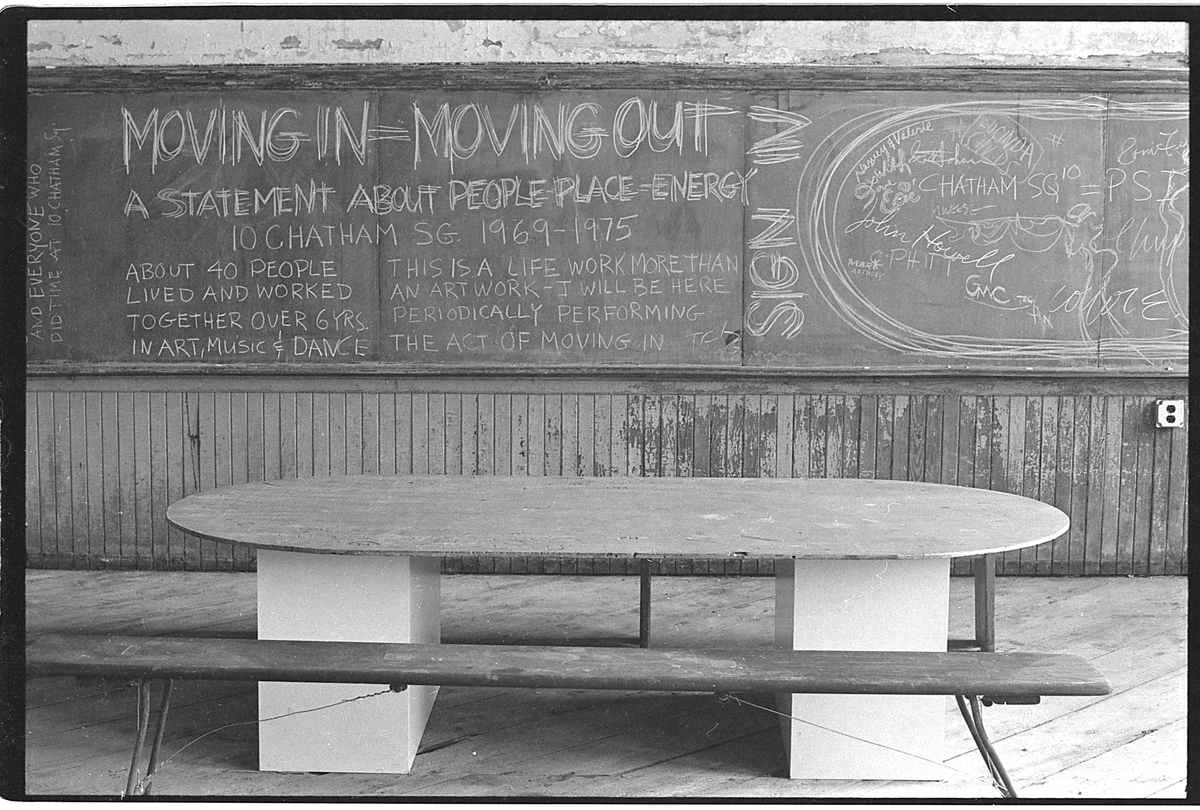

Tina Girouard, Moving In-Moving Out-Sign-In, 1976, Installation image of Girouard’s contribution to the exhibition ROOMS at PS1 in New York. Estate of Tina Girouard, Artist Rights Society (ARS) New York.

The works of artists are as important for the audiences they touch while they are living as they are for future generations. Preserving the way artists represent the world they see is crucial to our understanding of how we came to our moment, whenever that is. Holding onto the legacy of both artwork and artist (which can help contextualize the work itself) whenever possible can help ground a culture, a community, and even a moment in time.

Conversely, imagine the alternative. What might have been lost if the stories and work and legacies of artists involved with the Civil Rights Movement or the AIDS epidemic hadn’t been respected? How might our understanding of Depression-era America have been altered without the sustained preservation of WPA projects and murals?

— Jason Andreasen, president/CEO of Baton Rouge Gallery

Malaika Favorite

Malaika Favorite, Fear of the Next Disaster, 2022. Mixed media.

Art is a documentary record of the history of the times we live in. That does not mean that what we create must relate to a historical record, but that it shows how the individual artist created within the framework of his culture and times. Art is a visual diary of the artist as well as a reflection on emotions, realities, fantasies, and facts. Art can reach into the future and help people in future generations deal with their lives and learn from our lives. Art, like music, is not limited to language barriers, but it speaks to all cultures throughout the world.

I hope that my art will give joy or encourage the viewer to reflect on their own personal reality. I never want my art to be easy and decorative, for me it is important that what I do portrays layers of meaning that will never weary the viewer. Maybe it will make them smile, or cry, or just look at life from a different perspective.

—Malaika Favorite

Geismar, Louisiana

Favorite’s works are on display in an ongoing exhibition at the Southern University Museum of Art in Baton Rouge.

Trenity Thomas

Trenity Thomas, On Foot, 2021. Photograph.

My hope for my artistic legacy is that it will inspire future generations to embrace their individuality, creativity, emotional expression, and show how special the South is. I️ desire for my work to be a catalyst for conversations, reflection, and self-discovery.

Simply embracing your authentic individuality is the key to unlocking your full artistic potential.

—Trenity Thomas

Westwego and New Orleans, Louisiana

Thomas’s work will be featured in Louisiana Contemporary 2024, presented by The Helis Foundation at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art through October 13.

Alexander Stolin

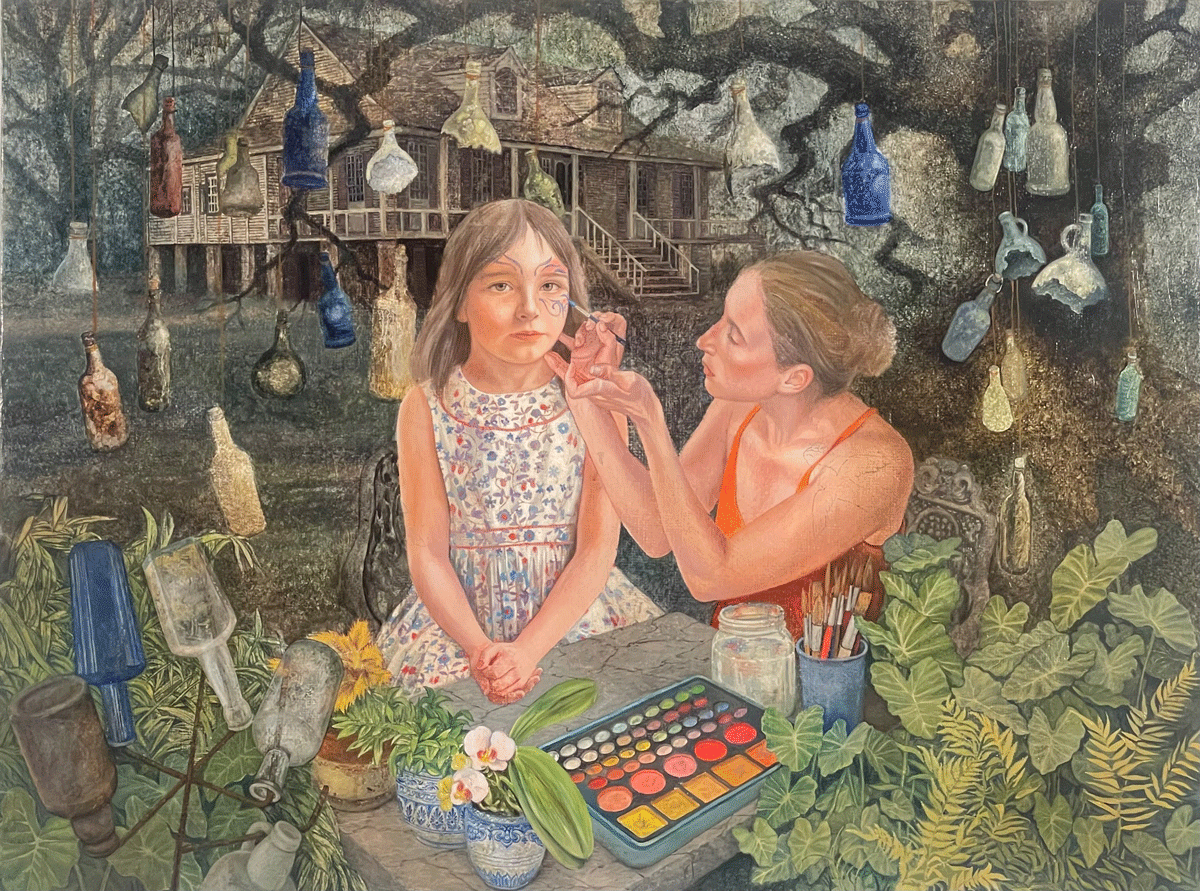

Alexander Stolin, Face Painting, 2023. Oil on canvas on board. Ferrara Showman Gallery

My desire is to have my artwork around my children, and maybe their children will connect to their roots and look at realities from different perspectives. The viewers will, I hope, pause and take a little time to reflect on their memories, experiences, and look from another angle, questioning, “How did I get here?”

The preservation of art is a legacy for future generations. Art in its various forms is a reflection of culture and history. Art conveys a unique identity, contributing to a collective memory. A continuum of artistic legacies for future generations is one of the paramount jobs of a civilized world.

—Alexander Stolin

Madisonville, Louisiana

Stolin’s work will be featured in Louisiana Contemporary 2024, presented by The Helis Foundation at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art from August 3–October 13.

Shawne Major

Shawne Major, Lodestar, 2021. Mixed media.

I hope that my works and concerns will remain relevant and stand out over time and be more than just about the here and now. I want my work to be loved hundreds of years from now. I’m always looking at the long view and am not interested in one-liner artwork. I hope future generations will appreciate my will to understand how personal reality is constructed and my need to create complex abstractions that mirror my inner worlds.

—Shawne Major

Henderson, Louisiana

Major’s work will be included in Louisiana Contemporary 2024, presented by The Helis Foundation at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art from August 3–October 13.

Vitus Shell

Vitus Shell, Gazing, 2022. Acrylic, paper, and foamcut on canvas.

I think my work speaks from a certain class, even within the Black community. . . . from a certain place, from a certain region. It speaks for me. I think I’m doing southern hip-hop with my work, so it speaks from what’s conceived as a low-level place within the community, but it speaks from people that don’t normally get to sit at the table and talk about their experiences. So I think it’s important in that sense that it gives people from the communities a platform to be heard or seen—and documented.

I think one of my main concerns as a living artist is I want people from my particular community to be seen, or know that they have a place, they have a platform to make and say things. . . that’s the legacy I really want to create. I want to create a place where artists, creatives, Black creatives, can learn new things, and explore their talent, and be able to give that to the world.

—Vitus Shell

Monroe, Louisiana

Shell’s work will be featured in A Bayou State of Mind at the LSU Museum of Art from December 12, 2024 until March 30, 2025.

Jeremiah Ariaz

Jeremiah Ariaz, photograph from the series Louisiana Trail Riders, 2018.

Artworks are the story of culture; they will communicate to future generations about the time we live in, what we care about, and what we fear. Archiving an artist’s labor feels important in a society where little value is placed on the time and efforts required of artists and that often sees art as only entertainment.

My work is a reflection of, and commentary on, the world we live in—including current events. In the past, I was more idealistic about the power of images to sway public opinion, but there seems to be little room for that in an increasingly polarized society. Now, I hope my work will offer a window for future generations to better understand our era.

—Jeremiah Ariaz

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Works from Ariaz’s series Hard Traveling Battleground Blues (Verse II) will be on view at Baton Rouge Gallery beginning October 2.