Tricentennial Excerpts

Excerpt: Big Time City

The transformation of Poydras Street marked a turning point for New Orleans in the 1970s

Published: November 28, 2017

Last Updated: December 6, 2018

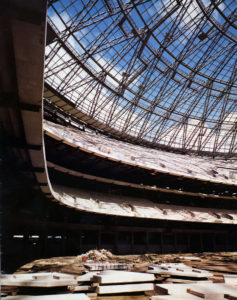

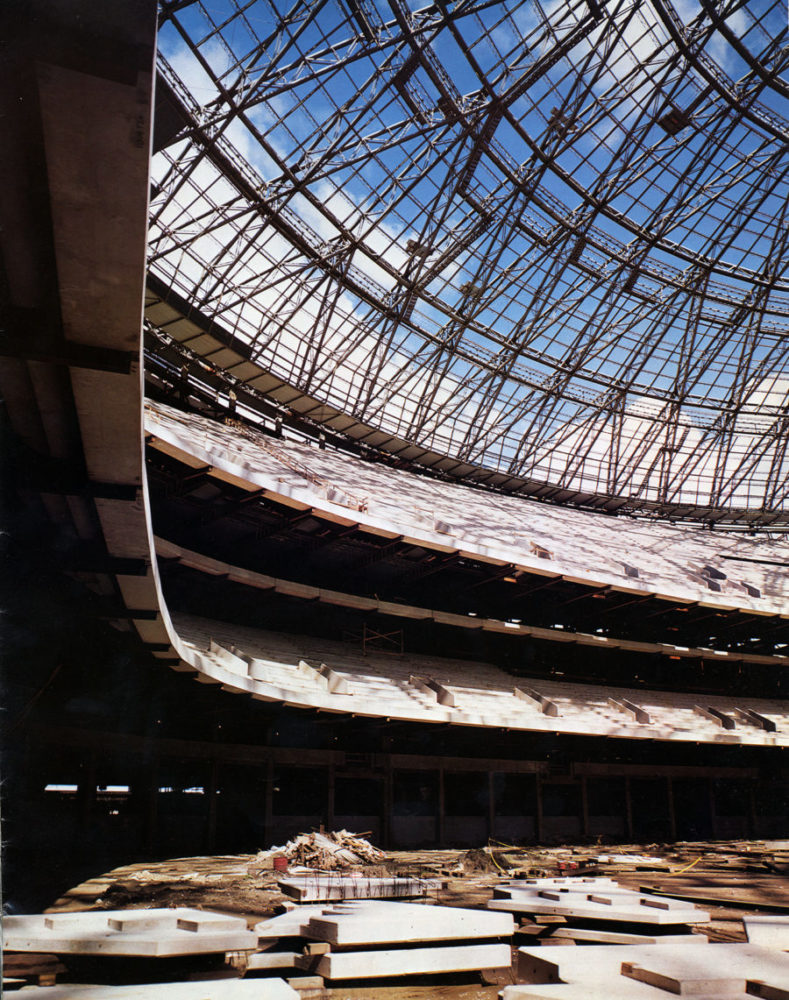

Photo: David M. Kleck

View of inside from inside the Superdome during construction, ca 1970s.

Note: The following is excerpted from New Orleans & The World: 1718-2018 Tricentennial Anthology, published by the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities. Click here to purchase a copy.

Even at the beginning of 1970, Poydras Street was starting to launch. Running 1.2 miles from old riverfront warehouses to the still-new Interstate 10 over Claiborne Avenue, it was about to become the most arresting physical manifestation of one of the most dramatic decades in New Orleans history. The transformation would happen quickly and would stop abruptly not long after the decade’s end. A booming oil industry would drive the construction, down Poydras, of more than a dozen Houston-class international-style corporate office towers—along with hotels and a new federal courthouse—before the bust came in the mid-1980s.But the 1970s marked more than this building boom. The decade produced dramatic changes in nearly all aspects of New Orleans life. It locked in place the main features of an urban landscape that wouldn’t remake itself again so thoroughly until after Hurricane Katrina. The changes jolted a second-tier city lagging behind the metro leaders of the New South into a more prominent role in the global economy and culture. A surprisingly vibrant economy supported the region’s optimism that the city was regaining lost stature, that an active port and booming oilpatch would make big new things possible. State and local officials believed in ambitious economic-development plans. The physical landscape—new office buildings and hotels erected faster and higher than ever before, old neighborhoods and historic landmarks treated with a new reverence—created a geographic pattern that would remain until well into the twenty-first century.

The decade produced dramatic changes in nearly all aspects of New Orleans life.

Social and political worlds were also becoming startlingly different from the previous decade, triggering more changes in the decades to come. The most important driver, which ran through every architectural commission, brass-band parade, and menu, was the change in race relations, revolutionized in large part by a new mayor who came to City Hall in 1970 determined to integrate business, society, and culture. Mayor Moon Landrieu personally accelerated the trajectory of the local civil rights movement that would get New Orleans closer to social justice. Landrieu’s election in turn had been propelled by the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which made black voters a powerful force in local government. Throughout the 1970s, New Orleans was a city successfully shaking off racial handicaps, nurturing a conviction that its economic future was big, taking pride in the character of its characters, and expressing an intense chauvinism about its food, music, and buildings. This in turn prompted confidence that tourism would become another major industry: if we like ourselves so much, then surely others will.

The year 1970 saw the first Jazz & Heritage Festival organized by producer George Wein. He had declined a 1962 invitation to stage a music festival because of the city’s persistent segregation. The push toward integration now appealed to him. After two successful launch years at Congo Square, Wein’s locally managed fest moved to the Fair Grounds racetrack infield, where it has been growing and cultivating local talent ever since.

Also in 1970, the city’s first restaurant critic, University of New Orleans history professor Richard Collin, published his Underground Gourmet guidebook and began a provocative weekly column in The States-Item. His ten years in that role unlocked a vibrant community conversation about food, chefs, and cooking that continues in a city where food is ever more important and everyone is a critic.

Ole Miss quarterback Archie Manning was chosen most valuable player of the 1970 Sugar Bowl game in New Orleans and joined the Saints in 1971. He stayed with the team into the 1982 season, braving losing seasons and sacks with such grace and skill that he cemented the Saints as the unifying factor it would become in New Orleans social life, able to bring fans across racial lines. The 1970s were the Archie decade.

In 1971, the influential book series New Orleans Architecture, by the Friends of the Cabildo, began its galvanizing eight-volume inventory of endangered neighborhoods and buildings, with the first six books published in nine years. Great scholarship and advocacy fortified the preservation movement. City Hall under Mayor Landrieu was often receptive to the preservationists and created historic districts and “growth management” policies that saved much of the city’s physical character even as it welcomed developers.

The early 1970s showed another New Orleans asset—capable news media. There were two substantive daily papers, including the afternoon States-Item, which had just been liberated from the control of its bigger brother The Times-Picayune and demonstrated its independence right up until 1980, when the papers were merged. At least two TV stations competed with quality news, including political scoops and investigations. And alternative weekly newspapers—The Vieux Carré Courier and the 1972 arrival Figaro—kept the rest of the media challenged and under scrutiny.

In 1970, the view up Poydras from the top of the thirty-three-story International Trade Mart, opened three years earlier at the foot of the street, was remarkable. The narrow four-lane portion near the river, long a utilitarian home to port-service businesses, had been widened to match the newer stretch beyond as it approached the interstate highway constructed in the late 1960s. The widening was conceived in the early twentieth century to help truck movement for the port. But that need seemed less pressing now. Poydras was seen after World War II as a key link to a Riverfront Expressway that would cross in front of the French Quarter as part of a region-wide network of big, fast highways. In the mid-1960s, under Mayor Victor Schiro, the street was expanded from 74 feet near the river end to 134 feet. But in 1969, the Riverfront Expressway was abruptly cancelled by the new Richard Nixon administration, which accepted preservationists’ warnings that the project would harm the French Quarter. And Poydras received a new mission. Schiro came to see it as a corridor of new corporate construction: “The Park Avenue of the South.” In the end, the street’s uniform use and design—a double row of tall new buildings used mostly by oil companies—almost looked planned.

In 1972, Joseph C. Canizaro, a young independent Mississippi-born developer, opened the Lykes Center. And that year Shell Oil Company moved into what is still the city’s tallest building, One Shell Square; it is almost identical to Shell’s Houston headquarters, One Shell Plaza, which opened the previous year. (Bill Rushton, tough-minded architecture critic for the weekly Courier, sized up the new Poydras style by labeling the New Orleans building “One Square Shell.”)

In 1970, the view up Poydras from the top of the thirty-three-story International Trade Mart, opened three years earlier at the foot of the street, was remarkable.

Local developers made space available for Texaco, Mobil, Amoco, Exxon, Gulf, Louisiana Land and Exploration, Freeport-McMoRan—most of which moved out of smaller, older quarters elsewhere in the Central Business District. Three of the Poydras Street towers went up directly across from the Dome. Two of the companies, Amoco and Mobil, were in the development that abutted the Dome, called Poydras Plaza, which also offered a Hyatt Regency Hotel and a headquarters for Entergy. At the river end of Poydras, the International Rivercenter proposed a Hilton Hotel and six other office and residential towers on twenty-three acres. Nearby, at the foot of Canal Street, was Canizaro’s Canal Place project, an office tower married to a shopping mall and hotel.

And then it all stopped. The price of oil dropped after 1980, kept sliding, and crashed dramatically in 1986, when Saudi Arabia put new supplies of crude on the market. It was “the worst recession to hit the Pelican State in modern times,” The New Orleans Advocate wrote in 2015. Businesses and banks closed, subdivisions were halted, Louisiana oil production virtually stopped, and the state’s unemployment rate became the highest in the country. There were doubts about whether oil reserves in the Gulf were still worth going after. Oil companies started to consolidate and leave town, back to their headquarters cities elsewhere, including Houston.

The last Poydras oil buildings in the developers’ pipeline were completed in the mid-1980s. Canizaro was last, in 1986, with the expensively finished Louisiana Land and Exploration building, which featured two large heroic sculptures by Enrique Alferez flanking the doors.

This is where the Poydras boom left the city, with enough office space to last decades. Even now, Poydras corporate buildings are being occupied by hotels—Loews for Lykes, Hyatt House for Mobil—serving as evidence of the city’s economic shift to heavier dependence on tourism and entertainment.

Jack Davis was a reporter and editor in New Orleans from 1972 to 1983, at Figaro, The States-Item and The Times-Picayune. At Tribune Company 1983–2007, he was metropolitan editor of the Chicago Tribune; CEO/publisher of the Hartford Courant in Connecticut and of The Daily Press in Virginia; and president of Tribune Interactive.