Magazine

The LEH’s home at Turners’ Hall

Built in 1868 for the Society of Turners, a German benevolent association, Turners' Hall has been the home of the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities since December 2000

Published: January 22, 2015

Last Updated: January 27, 2020

Editor’s Note: In December of 2000, the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities made its boldest move—literally—with the purchase of historic Turners’ Hall in New Orleans’ Central Business District. This 19th-century German social hall has since served as the Louisiana Humanities Center. As the LEH continues to serve the citizens of Louisiana in its historic headquarters, true to our mission of interpreting the past, we present a history of this venerable building and its former occupants.

Built in 1868 as a source of civic pride for New Orleans’ German immigrants, Turners’ Hall is now the proud home of the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities. Courtesy of Tulane University Archives

Built in 1868 for the Society of Turners, a German benevolent association, it was designed by William Thiel, a German-born architect and surveyor who worked in New Orleans from 1860 to 1869.

During that period Thiel also designed a synagogue for the congregation Tememe Derech on Carondelet Street, a hall for the Odd Fellows on Camp Street, and a meeting place for the Deutches Company on Bienville Street, as well as a number of New Orleans residential buildings and a synagogue for Beth Israel in Houston. Like his other known designs, Thiel’s hall for the New Orleans Turners imparted a sense of European-style imagery to a growing American city.

Thiel composed a giant order of pilasters to dominate the upper parts of the two facades overlooking the comer. They rise two stories, eight facing O’Keefe Street and five on Lafayette Street. Below the pilasters, heavy granite columns support a continuous granite lintel and a molded stringcourse. These define the original interior divisions between a street-level gymnasium and an upper-level auditorium adjoining offices and a ballroom. The building had faux bois doors between the granite columns and balconies beneath the third-level windows.

The Picayune called Turners’ Hall an “Aladdin’s palace, grand in character and design, and a worthy monument to the genius and patient labor of the population which called it into existence.”

The Society of Turners, also know as the Turn Verein, occasionally the Turn Gemeinde, and also as the Turners’ Association, had the building constructed as a meeting hall and gymnasium. Turners, or gymnasts, were popular organizations throughout 19th-century Prussia and the neighboring principalities of German-speaking peoples. Beginning especially with the large influx of German-speaking groups migrating to America following the 1848 wars of unification in Germany, many Turn Vereins were organized in the United States. A typical Turn Verein charter specified that the organization would be associated with the North American Turnerbund, and as such would pursue the goals of its statutes to educate members and “enable them to fulfill their duties as men and as fit and useful citizens.” The statutes also aimed to promote the welfare of the Turnerei (members) and to “contribute to the improvement of the German element in the United States” by unity among members and by cultivating and spreading “friendship and brotherly love.”

One of the rules of the Turnerbund was to “bring [each member’s] body to a uniformly strong development” through “sufficient practice in gymnastics and with arms of all kinds.” To meet that goal, all members who had not passed the age of 25 were considered “active,” and had a duty “to participate at all regular gymnastic exercises, as well as meetings.” Older members were not required to perform gymnastics, but were expected to attend meetings.

The chief officers of the Turn Verein were called “speakers.” Next were the first and second Turnwarts, with secretaries and treasurers, official janitors, a librarian, and a steward following in levels of authority. All business was conducted in German.

A two-story upper ballroom was transformed into three stories of loft office space within a naturally litatrium during a 1982 renovation by Errol Barron/Michael Toups Architects. (right) photograph by Robert Brantley, (left) by Allen Karchmer.

Germans in New Orleans

There was a “German Society” in New Orleans as early as 1850, and the Turner Society probably received its first New Orleans charter about that time.By 1854 the group had built a meeting house in what is now the first block of Loyola Avenue (Elk Place), between Cleveland and Canal streets. The Turners built this hall on land rented from a Michael Bock, from whom they held a lease running from 1854 to 1861. A document of 1855 makes it clear that the society conducted its meetings in this building at that time and that they were leasing a part of their building to a barkeeper, Henry Clasen.

The lease gave Clasen certain guarantees that the meetings and other activities of the local Turners would continue to be held in the same location throughout its duration, in light of expectations “to profit from the meetings of the association and other objects for which the said buildings have been used heretofore.”

The guarantee may have been necessary because it was generally known that the Turners were looking for a permanent site for a larger and more ambitious meeting hall and gymnasium. Not until 1867, however, did they find the “perfect” location, a pair of lots in the heart of the New Orleans business district. The property was in a mixed residential and commercial district, with a number of livery stables in the area and near the thriving Poydras Market. The Turners purchased the lots facing what was then Philippa (O’Keefe) Street at the corner of Hevia (Lafayette) for $7,500 in cash and short-term notes at a public auction of the estate of James Davern held on Sept. 17, 1867.

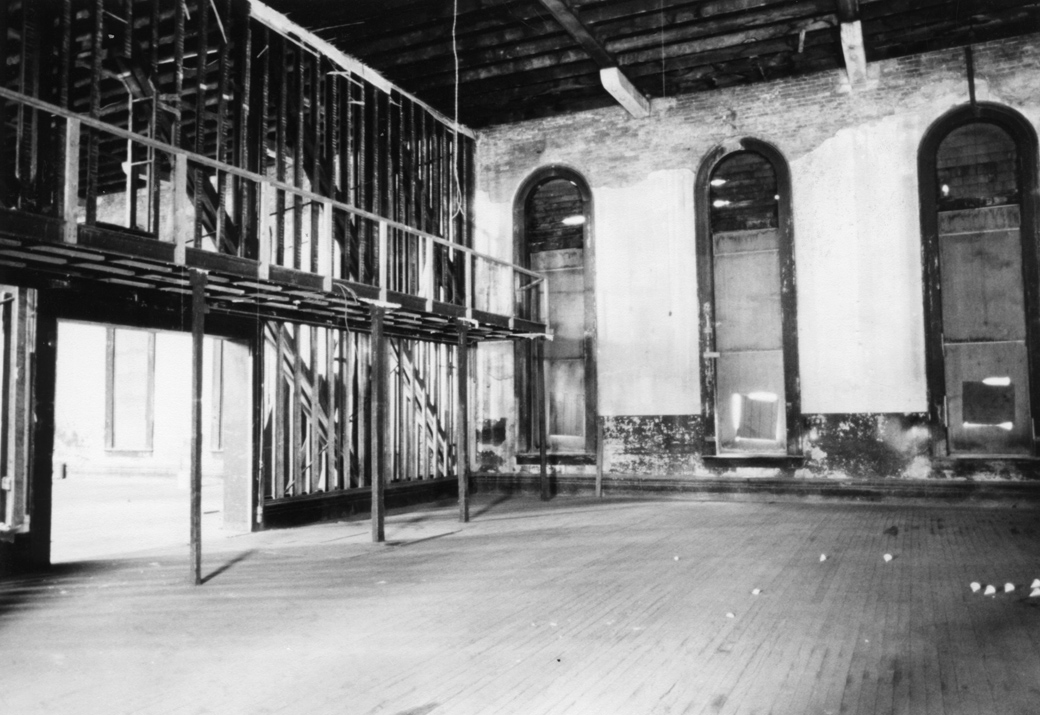

Turners’ Hall fell into decline during the mid-20th century. From 1955 to 1979, it served as a furniture warehouse and used appliance store. Photograph by Allen Karchmer

The land had been vacant for decades. The Second Municipality council had once purchased the lots, thinking to build a public school on the site during the late 1840s. By 1858, however, with the school yet unbuilt, the city’s three former municipalities reunited, and the John McDonogh bequest expected to fund more ambitious public schools, the New Orleans city council declared the lots surplus property. At the general Council’s direction, City Surveyor Louis H. Pilie drew a plan for another public auction of these lots, along with other properties declared surplus at the time. The plan—showing the two lots each having 31 feet, 11 inches of frontage on Philippa by 127 feet, 10 inches on Hevia and dated March 31, 1858—is in the collection of the New Orleans Notarial Archives.

James Davern purchased the plot from the city on May 11, 1858, and held the land undeveloped. Nine years later, his succession sold them to what was then identified as the “Turngemeinde” for $7,500, more than twice Davern’s purchase price of $3,450, reflecting the inflationary post-Civil War environment. Longtime Turner treasurer Salomon Schmidt, along with S. Aufheusen, and M.T. Sibelsky signed the various documents leading to and including the sale in October 1867.

The Turners lost little time getting their new hall started. By August 1868 architect William Thiel had finished three drawings for the new hall showing an elevation with the original balconies of the third floor supported by iron brackets, the brickwork, a rear gallery, outbuildings, and a roof framing scheme. On Aug. 18, 1868, the Turners contracted with builder Thomas O’Neill to construct this building and its dependency for $39,758.

The plan was to complete the building in six months and O’Neill met the schedule. Inside, the finished building had a hall, gymnasium, and store on the ground floor. On the second floor was a library. A ballroom with a stage occupied the third floor. The Turners furnished the building with nearly 1,000 chairs, a piano and violin, eight mirrors, desks, tables, pictures and statues, a library stocked with sheet music, arms, drums, flags, theatrical scenery, and club insignia. Five paintings were hung in the ballroom. There must have been a celebration when the building was occupied. The Picayune called Turners’ Hall an “Aladdin’s palace, grand in character and design, and a worthy monument to the genius and patient labor of the population which called it into existence.”

Two-story floor-toceiling windows grace what was once a ballroom at Turners’ Hall. Photograph by Allen Karchmer

Change of Ownership

Not all Americans found the American Turnerbund charming, however. Just two years after the New Orleans hall was completed, Mrs. Jennie F. Willing, a member of the Methodist Episcopal Church of Cincinnati, published an article entitled “The Sabbath” in The Ladies Repository, published by her local church. In the view of Mrs. Willing, the activities of both the Turners and the Sangerbund, another German organization devoted to singing, “desecrated” the holy day.“Witness the Sabbath desecrations of the tum verein and the sangerbund,” she wrote. “If they have a high day, it is always on Sunday—bands of music, banners, noise, dust, beer drinking, and debauchery.” Their aim was “reconstruction,” she wrote. It was to “overturn the bigotry that fences in the Sabbath and hinders good foreigners from going upon that day to their bier gartens, to carouse and dance, get drunk and break each others’ heads.” Mrs. Willing, sounding something like a nativist, went on to attack the Papists in her article.

A conference center on the fourth floor provides space for LEH board and staff meetings. Photograph by Robert Brantley

But if the Tum Verein of New Orleans was true to form, one suspects that the Lafayette Street hall was indeed the site of drinking and good times, even on Sunday, and even in Reconstruction-era New Orleans. The city had its temperance adherents, but one rather doubts that the New Orleans Turners met with as much disapproval of their singing and beer drinking as did those of other American cities. For decades, visitors like Benjamin Latrobe had commented that New Orleans natives were tolerant of Sunday drinking and dancing, and since colonial times, the city had been full of comer taverns known euphemistically as “coffee houses.” By 1850 New Orleans also had a number of beer halls, as the numerous acts of notaries who catered to European foreigners during the mid-19th century attest.

It was not social pressure but financial trouble that was rising to challenge the Society of Turners, even as they took possession of their handsome new building. To acquire the land and build the hall, they had taken on a burden of nearly $50,000 in an era when prices were high, cash was short, the economy was in crisis, and long-term financing was almost nonexistent. A year after the building was completed, builder Thomas O’Neill had received only $15,000 of the nearly $40,000 owed him, and the board decided to issue $25,000 in bonds to raise money to settle his account. O’Neill, hoping thereby to receive full payment, had to settle for a second mortgage on the building in order to prime the debt to the bondholders. This was agreed, and Turner president John C. May and secretary L. R. Jacoby issued the bonds in March 1869. The longest maturity they could get was five years at an 8-percent semiannual coupon.

The following year, treasurer Salomon Schmidt prevailed upon the Union Bank to lend the society another $9,000. Eighteen promissory notes with interest payable monthly and another mortgage on the building secured this note. A mortgage instrument of April 20, 1870, essentially converted the floating bank debt to a second mortgage after builder O’Neill appeared to acknowledge that he had been paid and gave the Turners a release on his earlier claims. It was now the spring of 1870. The Turners owed $25,000 to the bondholders, $9,000 to the bank, an indeterminate amount on the land, some taxes, and some accounts payable.

For four years, faithful Salomon Schmidt, perennial treasurer, liquidated accounts payable out of his own pocket when the organization was strapped. This went on until early 1874, when it could no longer continue. On Feb. 27, 1874, officers John Keller, Leo Stegle, George Gustave Koschel and Valentine Stubenrauch ceded to Schmidt every movable asset the Turners owned. They gave up everything in the building paintings, furniture, arms, books, flags, the chairs in the hall, even the scenery on the stage—all of it valued together at $1,680, to repay him for his personal advances. The future must have looked dim for the New Orleans Turn Verein.

If the Turn Verein of New Orleans was true to form, one suspects that the Lafayette Street hall was indeed the site of drinking and good times, even on Sunday, and even in Reconstruction-era New Orleans.

A New Start

In November 1875, a group incorporated as the “Germania Turn Verein.” This may have been a rival organization, or a reincarnation of the older society.Perhaps there were internal struggles. Some members may have wanted to declare bankruptcy. In any case, there was a new tone to the documents. Members had to pay an admission fee to the club house. They had to pay dues every month or lose their membership. Those who revealed the content of secret sessions were expelled. There were new officers and a new seal. The new regime seems to have lasted until January 1879, when the organization changed its name again to Turn Verein of New Orleans, increased the dues, and amended the charter to re-emphasize the organization’s purpose as a benevolent society. The “Treasury” was redefined as a fund to aid members. Those who were sick were to receive $7 a week in aid, up to $50 per year. Rules about expulsions over secret meetings were eliminated, and provisions made to give those in arrears on their dues time to pay up. At the death of any member, every other member was required to pay an extra 50 cents and attend the funeral.

In 1877, the Germania Turn Verein purchased a lot on Clio Street between Dryades and Rampart Streets and moved to a new location in what is now Central City. Whatever their relationship was to the older organization, it was too late to save Turners’ Hall. Builder Thomas O’Neill and several others, probably bond holders, filed suit against the Turners in 6th District Court in 1878. Pursuant to this suit, the Orleans sheriff seized the Lafayette Street hall and sold it for debts to a consortium of New Orleans insurance companies on June 19 of that year. The consortium was led by Herman Zuberbier, president of the Germania Insurance Company of New Orleans, who may have leased the building to the older Turners group for a while, or converted it to other uses. This all ended in 1883 when Germania and four other companies as well as several individuals sold their joint interests in the hall to James B. Moore and Company. At this point, grand Turners’ Hall probably became a machine shop.

The “Turn Verein of New Orleans” survived for several more generations. As late as 1929, they still had the Central City meeting place, which they sold to the Deutsches Haus at the end of that year. The Deutsches Haus, a happy beer hall patronized by residents throughout the region, survived at 200 Galvez Street until 2011 when it was demolished to make way for a new hospital complex. Plans to build a new Deutsches Haus building along Bayou St. John near City Park are currently underway.

The most distinctive exterior feature of Turners’ Hall is a tromp l’oeil mural at the front end featuring stylized window panes and columns. Hidden within the mural is a replica of the front cover from the Summer 1999 edition of Louisiana Cultural Vistas.

Decline and Rebirth

James Bradner Moore and a partner, John Middleton Huger, paid only $9,000 for Turners’ Hall in 1883. When they purchased the building, it was still known as Turners’ Hall, but it now contained machinery, boilers, pumps, reservoirs, filters, pipes, and pulleys.It may have undergone a conversion to some kind of industrial use during the four years that the Turners’ creditors controlled it, and possibly earlier. The Shakespeare Iron Foundry was in the same square in this period, at the end of the block of Dryades at Girod. The neighborhood area was changing.

Moore & Company turned out to be no more solvent than were the Turners. Within two years, their own creditors were suing, forcing a sheriff’s sale that took place Feb. 21, 1885. The Board of Commissioners of the Tulane Education Fund now purchased the hall for $11,100 as part of its investment portfolio of downtown New Orleans real estate. Tulane retained the property for 58 years, the longest owner in Turners’ Hall’s history. The university no doubt had a series of tenants. One of these was Steeg Printing and Publishing Company, which also did some bookbinding.

By 1948, Turners’ Hall had become a furniture store. The Matthews Furniture Company, owned by Jefferson Davis Matthews and Samuel Heide, were there at least from 1943 to 1948. Joseph P. Meyer and Carl Goldenberg were the owners between 1948 and 1955. The Labiche family purchased the hall in 1955 and used it as Labiche’s furniture warehouse and used appliance store until 1979. The building was converted into office space after that time for the Qualicare Corporation of Louisiana, with Errol Barron/ Michael Toups Architects dividing the great interior spaces, both horizontally and vertically, and converting the building to office use.

Turners’ Hall will have a new life in the 21st century under the aegis of the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities. While there is a great deal more to learn about its history, there is also much more history for it to make.

——-

Sally Reeves is a retired archivist for the New Orleans Notarial Archives.