View from a Windowless Room

The Angolite provides a journalistic outlet for the incarcerated

Published: August 30, 2019

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

The Angolite

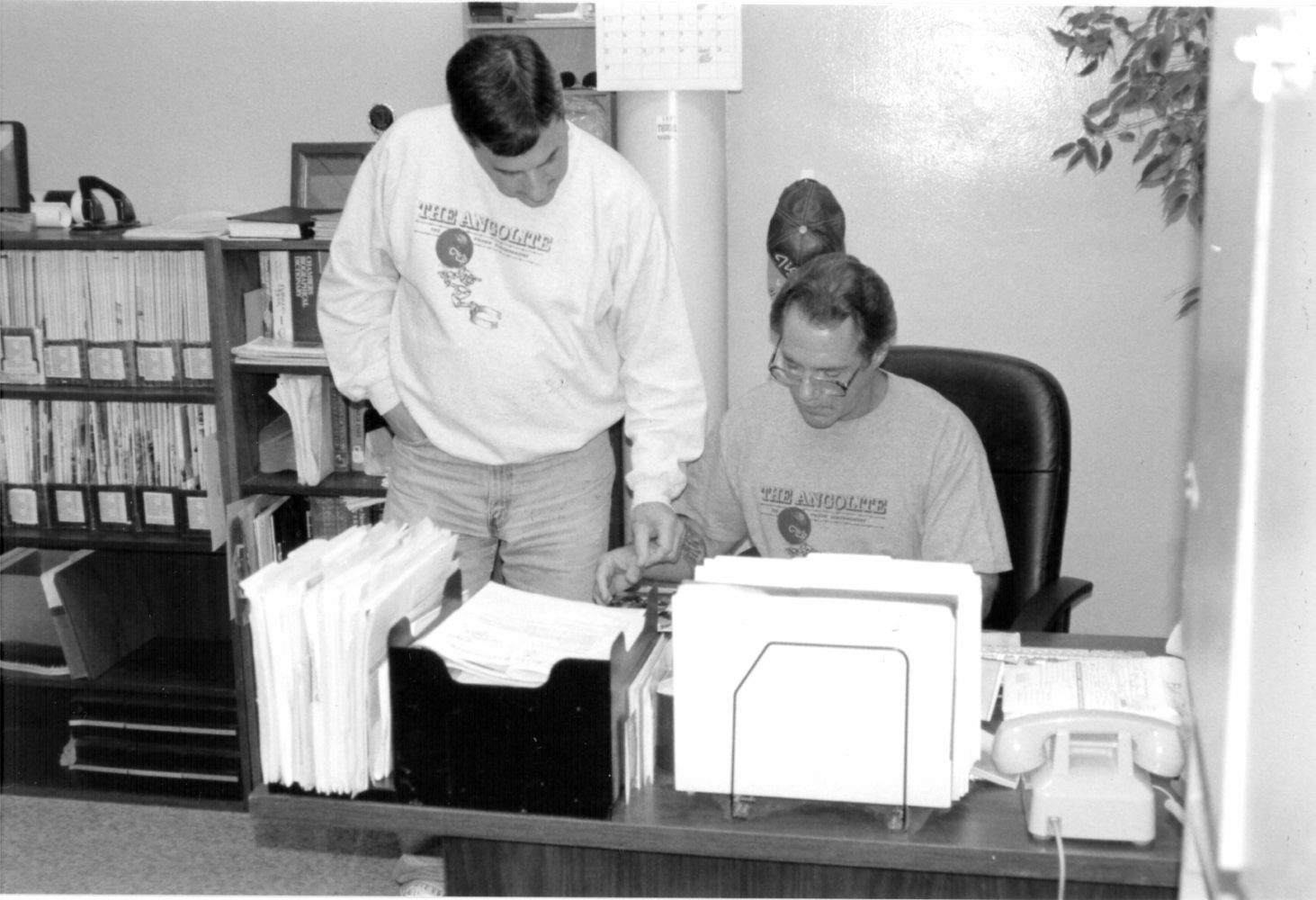

Kerry Myers (left) and Lane Nelson at work on the magazine.

Edited and produced by prisoners who are usually serving life sentences—76 percent of Angola’s population are serving life—the magazine has an international reputation for its straight-forward portrayal of the day-to-day inside a notorious maximum–security prison and for being on the cutting edge of Louisiana’s and the nation’s most significant criminal justice issues. For this work, the Angolite has received multiple prestigious national journalism awards, going head–to–head with mainstream publications.

For twenty years, sixteen as editor, I was part of this anomaly, this rare experiment that allowed a small group of incarcerated men to have a voice that reached beyond the windowless room and into the newsrooms of state and national media, the halls of academia, the law libraries of ivy-covered institutions, the United States Supreme Court, and the homes of an ever-growing number of families affected by mass incarceration. With a small staff, most of whom recognized the gravity of the work, alongside a few diligent and dedicated souls who never quite grasped its role or reach, the magazine persevered through political, supervisory, and institutional changes that at times made it feel like we were fighting the very systems and people who consigned us to do the job. The continued existence of the Angolite is a testament to the writers, the readership, and those corrections officials who, in the face of pressure from a wide range of sources, believed in the magazine’s relevance as a journalistic institution.

Working for the Angolite is a coveted job. Never were there more than seven positions available, and turnover is rare. The pool is also shallow, though tradition has allowed each editor the courtesy of selecting his own staff.

My main criterion for choosing staff—a lesson learned from my predecessor Wilbert Rideau, who guided the magazine for twenty-five years—was character. That may strike the uninformed or misinformed as an ironic standard inside of a prison. Character flaws are what led most there. But writing or photography or computer skills—which are certainly important to the production of a magazine—can be taught. Character cannot. Vetting candidates was important; it was essential, even critical, that our small staff could trust each other and be trusted with the institutional integrity of the magazine. My position as editor also taught me a lot about human nature and about how education or middle-class advantages do not necessarily indicate intelligence or character.

In 1976, a bold experiment… transformed the Angolite under new editor Wilbert Rideau from a gossip-and-farm–news newsletter to a journalistic publication. The mandate: to operate with the same professional standards used by mainstream publications.

The Angolite is a full-time job. For staff, productivity and work ethic are not incentivized by compensation or vertical mobility. The job itself is the reward, providing trusty status that allowed its staff a significantly higher degree of movement within the prison, as well as access to information, people, and technology that most prisoners did not have. Just another reason for placing so much emphasis on character. Staff earned the maximum–allowed twenty cents per hour, performing multiple roles as reporters, writers, photographers, and researchers. An issue averaged seventy-two pages of content; we sold no advertisements. The production process differed from mainstream publications only in the way information was gathered and the conditions under which the magazine was produced. The days were long and frenetic and always bled into nights, which were the preferred time to write and design, offering fewer distractions and more continuity.

Published bi-monthly since the mid-1970s, the Angolite has a paid subscriber base that fluctuates between 1,000 and 1,500, not including another 1,800 issues distributed free inside the prison. While the vagaries and immutability of daily life inside Angola often affected timely publication, subscribers were never shortchanged.

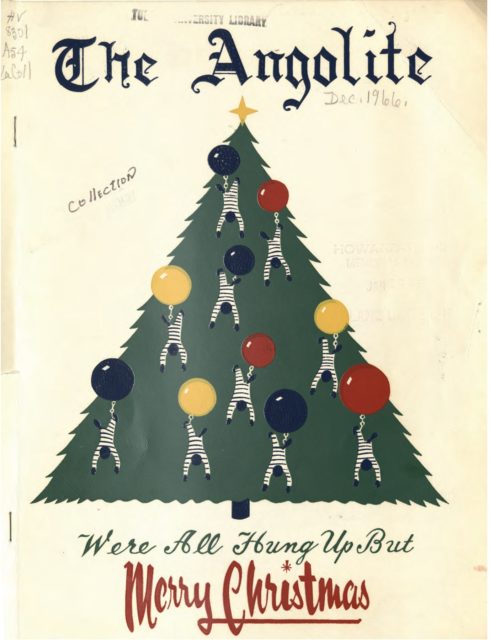

The original gossip-and-farm-news incarnation of the Angolite still made occasional comments on prison realities, as the tag line and ornaments on this 1966 cover attest. Louisiana Research Collection, Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, Tulane University.

The job made endless days, months, and years anything but ordinary or routine in a place where routine infects daily life like a contagion. Our work was also defined by layers of contradiction. First published in 1953 as a tabloid newspaper, the Angolite reported on crop production and sugar refinery output, construction projects and jobs, sports, calendar events, weekly population movements, and parole and pardon results. It included a chaplain’s corner, the occasional warden’s message, and columns from “camp correspondents,” including one from the female prisoners segregated at old Camp-D (Angola held women from 1901 to 1962). Then, as now, the editor determined content, but a hint of contradiction is glimpsed in a 1953 article published by the Morning Advocate in Baton Rouge, which quotes the prison education director saying that the administration encouraged the editorial tone to be “light and cheery.”

In 1976, former state corrections chief C. Paul Phelps launched a bold experiment that transformed the Angolite under new editor Wilbert Rideau from a gossip-and-farm–news newsletter to a journalistic publication. The mandate: to operate with the same professional standards used by mainstream publications.

This gave the editor unprecedented freedom to shape the publication’s editorial mission and determine content. Reporting assignments and feature articles were based on subject relevance. The editorial mission became to inform, educate, and enlighten a readership that included not only the prison population but also local, state, and national media, lawmakers, policymakers, legal communities, and scholars.

No official censorship policy exists at the Angolite, and since the mid-1970s the magazine has branded itself as uncensored. While prison officials do not dictate what is written, each issue goes through an administrative review before going to press. At any publication, the relationship between the editor and publisher often exists in tension; this tension is understandably heightened at the Angolite, considering that the publisher is the warden. Walking the ever-shifting line to remain credible with both the readership and the publisher was a mixture of acquired skill and luck. Reporters, visitors, and others often asked me about censorship; my answer, honed though experience, was “We do not practice suicidal journalism.” Subjects not tackled by the Angolite were as telling as the ones we did cover. Existing, having a voice, was better than silence. Nationally acclaimed articles on the death penalty, juvenile lifers, judicial corruption, policy by politics, penal history, and more kept the Angolite journalistically relevant; a bit of self-censorship kept it alive. This is not to say that what we did and did not publish was a casual choice made without pain and careful reflection. Finding the line, straddling the line, even pushing the line—this was, as I learned from my years working under Rideau, the editor’s blessing and curse.

The swirling of political winds and the whims of wardens did not prevent the magazine from building and maintaining a reputation for insightful reporting that often anticipated the most important criminal justice issues. Unable to compete with mainstream outlets for subject–matter immediacy, we instead focused on depth and analysis, along with our unique asset, personal stories, to give readers a perspective on issues they could not and would not get anywhere else. Adhering to the doctrines of objectivity and balance, the Angolite put human faces on stories of ruin and redemption.

Gathering information for an in-depth feature story was no easy task from inside prison. For a while after I joined the staff in the mid-1990s, the Angolite could receive phone calls from news sources, other journalists, article subjects, academics, experts, and others. We could also make phone calls through the prison’s switchboard. But politics drive policy, and when the political winds changed to become increasingly punitive, we lost the privilege of easy outside communication. So we improvised. We accessed as many commercial, government, private, and academic reports and studies on our subject matter as we could. We accessed the Department of Corrections data and personnel. And we had what no other publication had—the stories of five thousand individuals who lived all around us. By the early 2000s, when paper publication of our usual research sources was dramatically reduced in favor of online publication, we nearly lost the ability to use these sources, since internet access is considered a threat to prison security and strictly prohibited. Our guardian angel came in the form of a retired criminal justice professor who collected research from specific requests. With administration approval, she burned the information onto a CD which the prison’s IT department would then transfer to the magazine’s server to be catalogued.

We were often approached by people who wanted their stories told. My editorial policy was to eschew the typical personal profile for several reasons, one being that we would do our due diligence of fact checking and research, which served as a formidable deterrent. Instead, Angolite staff wrapped individual stories around broader examinations of issues like draconian sentencing policies, drug laws and enforcement, sex crimes, the death penalty, policing and prosecuting, the effects of crime and incarceration on families and communities, and the corruption of officials.

The Angolite is and should remain a voice in the wilderness, a voice that provides a much-needed antithetic, realistic view of our criminal justice policies… The men and women in our prisons are not just numbers: they are fathers, sons, husbands, daughters, wives, and mothers, and most are more than their worst act.

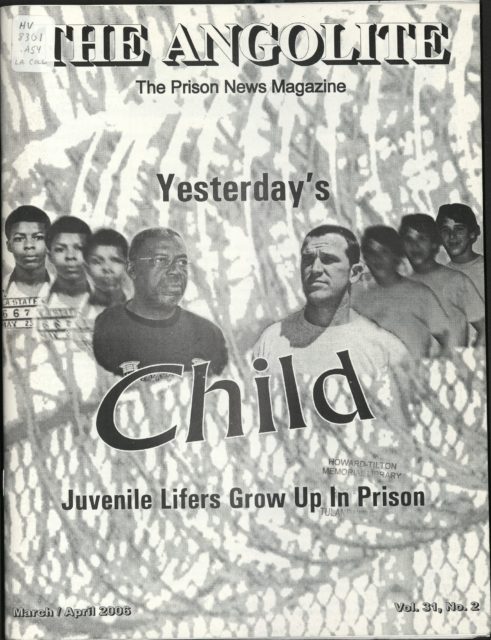

Journalists win awards for stories that have social, historical, community, or political impact. We were fortunate to have published a few. In 2007 the Angolite received the Thurgood Marshall Journalism Award given by the Death Penalty Information Center for our cumulative reporting on the death penalty. In 2011 we won the Prevention for a Safer Society Award from the National Council on Crime and Delinquency for a feature article about juvenile lifers—persons sentenced to mandatory life without parole as adults for crimes committed when they were children. Two years later the US Supreme Court ruled that those sentences were unconstitutional. The magazine also exposed a decade-long practice by a state appellate court of routing pro se supervisory writs (appeals filed by prisoners unrepresented by counsel) to an administrative employee, who issued canned answers, all denials, without a single judge or judge’s law clerk ever having seen the filing. The practice violated state law, and as a result of the Angolite’s coverage, the practice was ended. Even from a windowless room, our voices sometimes made a difference.

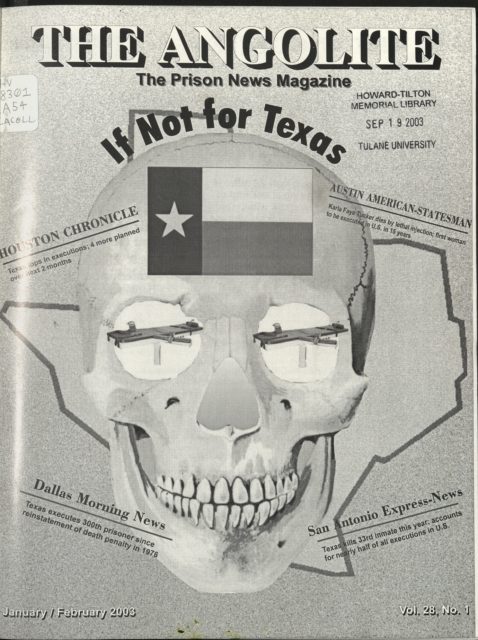

The hard reporting the Angolite offered under Myers won awards for its coverage of the death penalty and juveniles sentenced to life imprisonment. Louisiana Research Collection, Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, Tulane University.

It feels like someone else’s life now, those twenty years of both pressure and personal gratification to write for and guide the editorial direction of a magazine that is an institution and, I believe, a state and national treasure. As I steadfastly maintained my innocence every moment of my nearly twenty-seven years of incarceration—an assertion echoed by the victim’s family and the investigating detective—I found editing the Angolite to be my tether to reality in the most surreal of circumstances. It is not much of a stretch to say the job saved my sanity, or at least my sense of self. It provided purpose and a reason to get up each morning, and allowed us to shed light on the people who live in, work in, and make the policies that determine the course of our criminal justice system.

It feels like someone else’s life now, those twenty years of both pressure and personal gratification to write for and guide the editorial direction of a magazine that is an institution and, I believe, a state and national treasure. As I steadfastly maintained my innocence every moment of my nearly twenty-seven years of incarceration—an assertion echoed by the victim’s family and the investigating detective—I found editing the Angolite to be my tether to reality in the most surreal of circumstances. It is not much of a stretch to say the job saved my sanity, or at least my sense of self. It provided purpose and a reason to get up each morning, and allowed us to shed light on the people who live in, work in, and make the policies that determine the course of our criminal justice system.

The Angolite is and should remain a voice in the wilderness, a voice that provides a much-needed antithetic, realistic view of our criminal justice policies. Louisiana led the nation in per capita incarceration for a decade (it lost that title late last year to Oklahoma), and the United States, with 5 percent of the world’s population, holds 25 percent of the world’s prisoners. The men and women in our prisons are not just numbers: they are fathers, sons, husbands, daughters, wives, and mothers, and most are more than their worst act. For nearly four decades in Louisiana we have embarked on a one-size-fits-all criminal justice policy in the name of public safety. Nearly five thousand men and women, 15 percent of our prison population, are serving life sentences. Almost half are first offenders. We now spend nearly eight hundred million dollars a year on corrections without an appreciable return on the investment.

The Angolite is, indisputably, a valuable piece of American journalism. Criminal justice and law programs throughout the country use its content as a teaching resource. It provides mainstream media and policy makers with a rare insight into life inside of prison. But sometimes it can be difficult to believe the long hours of research and writing, editing and design to produce a magazine from prison truly make a difference. Feelings of futility, fueled by frustration with the daily fight to do the job, have a way of obscuring reality. But every now and then, the voice of the magazine makes the view from the windowless room crystal clear.

Kerry Myers is the deputy director of the nonprofit Louisiana Parole Project. In 1990, he was sentenced to life without parole for second–degree murder, a crime he, the victim’s family, and the investigating detective steadfastly maintain he did not commit. In December 2016 Myers’s sentence was commuted, and he was immediately released. In prison, he edited the national award-winning Angolite magazine and was recognized with the Thurgood Marshall Journalism Award in 2007, the 2011 Prevention for a Safer Society Award for Journalism, and three APEX Awards of Excellence for Magazine and Journal Writing. He is a contributing author to the recently released, critically acclaimed book The Meaning of Life: The Case for Abolishing Life Sentences, co-authored by Marc Mauer and Ashley Nellis of the Washington, DC–based policy group the Sentencing Project.