Latest

Welcome to the Jungle

Edwin Edwards, democratic reform, and political confusion in Louisiana’s open election system

Published: September 11, 2023

Last Updated: September 25, 2023

Nixon Presidential Library

President Richard Nixon and Louisiana Governor Edwin Edwards, July 31, 1972. Detail from a photo by Oliver Atkins.

The Louisiana Democrat, who represented the Seventh Congressional District—Cajun country—sought to become the state’s fiftieth governor that year, just as the political climate in the Pelican State was changing. Sitting Governor John McKeithen, a Democrat completing his second consecutive term, was constitutionally ineligible to run, opening the way for a host of Democratic hopefuls. The crowded primary field included an array of well-known politicians and public figures besides Edwards, including Lieutenant Governor C. C. Aycock, African American attorney Sam Bell, former Governor Jimmie Davis, State Senator J. Bennett Johnston, Congressmen Gillis Long and Speedy Long, and grocery store magnate-turned-politician John Schwegmann, along with nine others.

Edwards barnstormed the state with his home-spun humor and flash. In the age before substantive election finance reform, money flowed fast and loose as the Edwards camp spent its capital at a prodigious rate. On election day, November 6, 1971, approximately 78 percent of registered voters turned out. When the results were tabulated, Edwards led the pack with over 23 percent of the vote. Johnston came in second, fielding slightly above 17 percent of the returns. With no candidate securing more than half the vote, a runoff election was scheduled for December 18. Although differing in style and temperament, Edwards and Johnston both claimed to be reform candidates. Louisiana’s tumultuous history, which included the Civil War and Reconstruction periods, prompted the development of a solidly Democratic state that retained its hatred of the GOP (the party of Lincoln that helped end slavery) well into the twentieth century. With the majority of the state’s voters participating in the Democratic primary, the election results demonstrated that Louisianans were clearly tired of the status quo.

The Democratic Party runoff gave Johnston the early lead, but Edwards soon closed the gap and pulled ahead for good. As he took the lead, an ebullient Edwards allegedly jumped on a table at his election night party and shouted, “Let’s give three cheers for the coonasses!” When the final tally was revealed, Edwards won the tightly contested race by a little over five thousand votes, many of them coming from South Louisiana’s Cajun French-speaking Catholic voters, who rewarded a native son of the region with lopsided victories in the southern parishes.

After facing two bruising Democratic primaries, Edwards had one more campaign to mount before becoming Louisiana’s new governor. He next faced the Republican Party’s nominee, David Treen, in the general election. In the early 1970s, while white voter allegiance to the Republican Party was just on the horizon, Louisiana remained an overwhelmingly Democratic state, and success in the Democratic Party primary was tantamount to winning the general election.

Although confident of success, Edwards had already fought two difficult campaigns. Those early battles introduced statewide voters to Edwards, an engaging, albeit over-the-top, showman who promised to save the state money and bring needed reforms. If nothing else, he was certainly entertaining. At the same time, the extensive scrutiny of his personality and investigations into his political record during the primaries wounded Edwards. Plus, voters learned he was thin-skinned and lashed out when criticized. Likewise, Edwards garnered attention for allegedly promising the African American community that they would receive patronage rewards should he secure the governor’s post. With memory of Jim Crow in the not-too-distant past, promises of assistance to the African American community did not sit well with many white Louisianans who still harbored considerable racial prejudice.

It had been an exhausting five-month campaign for Edwards in which he faced three elections before coming out on top. The newly elected governor learned many lessons on the campaign trail and had many promises to keep.

Despite his political baggage, Edwards, as expected, easily secured victory in the February 1, 1972, general election against Treen, whose easy ride to victory in the Republican primary left him unscathed but under-the-radar. Hinting at the future, Treen’s 43 percent of the popular vote proved substantial since the GOP constituted a mere 3 percent of registered Louisiana voters. Although Treen lost handily, the Republican Party took solace in the fact that its share of the electorate had grown while running a gubernatorial candidate who had yet to hold public office and thus had little track record. Once again, Edwards credited “Cajun power” for his success since his margin of victory was secured in South Louisiana. It had been an exhausting five-month campaign for Edwards in which he faced three elections before coming out on top. The newly elected governor learned many lessons on the campaign trail and had many promises to keep.

Despite initial successes as governor, the most important of which was the adoption of a new streamlined state constitution to replace the cumbersome 1921 document, hints of the roguish behavior that would plague Edwards’s career also appeared. In his first term, Edwards fell under an Internal Revenue Service probe for obstruction of justice in an income tax investigation of the governor’s personal finances. At the very moment Edwards began fielding press inquiries about his personal misconduct, he announced, in April 1975, his desire to abolish the state’s party primary system. In its place, Edwards proposed the adoption of a pioneering “open election” model in which individuals seeking an office appeared on the election day ballot without regard to party identification. Under the plan, all registered state voters could run. If the top vote-getter received a simple majority, he or she would be declared the winner. Otherwise, a runoff election would be scheduled between the two top candidates.

In making his case for the reform, Edwards contended that the open election system would benefit the Republican Party because voters, who might have registered as Democrat solely to influence the state’s political system, would switch to the Republican side under the proposed changes. According to Edwards, the Republican Party had “nowhere to go but up,” given the small number of GOP voters in the state. He also trumpeted the reduction in the number of costly state elections—the benefit that was perhaps most important to Edwards, who remembered his own protracted election campaign for governor.

After days of legislative wrangling over particulars in the state House and Senate, the open election law was signed into law by Governor Edwards on May 30, 1975, thus ushering in a sometimes maddening, always intriguing new era in the state’s colorful political history.

Initially, the new system applied only to state and parish-level elections. Until 1978 all federal elections remained under the old party primary system. After that year, only presidential contests followed the party primary model. Open elections for all state and parish offices would be held the first Saturday of November (this would vary across time with the initial referendum in the state held at various points between September and November), with the general runoff election scheduled on the sixth Saturday following the first vote. Despite their initial skepticism, Republicans found that Edwards had been right: as the open election system took root, Republican officeholding boomed.

For Edwards, the pesky allegations of federal crimes were buried beneath stories of his manifold reform initiatives. He would go on to win a second consecutive term, and two additional terms.

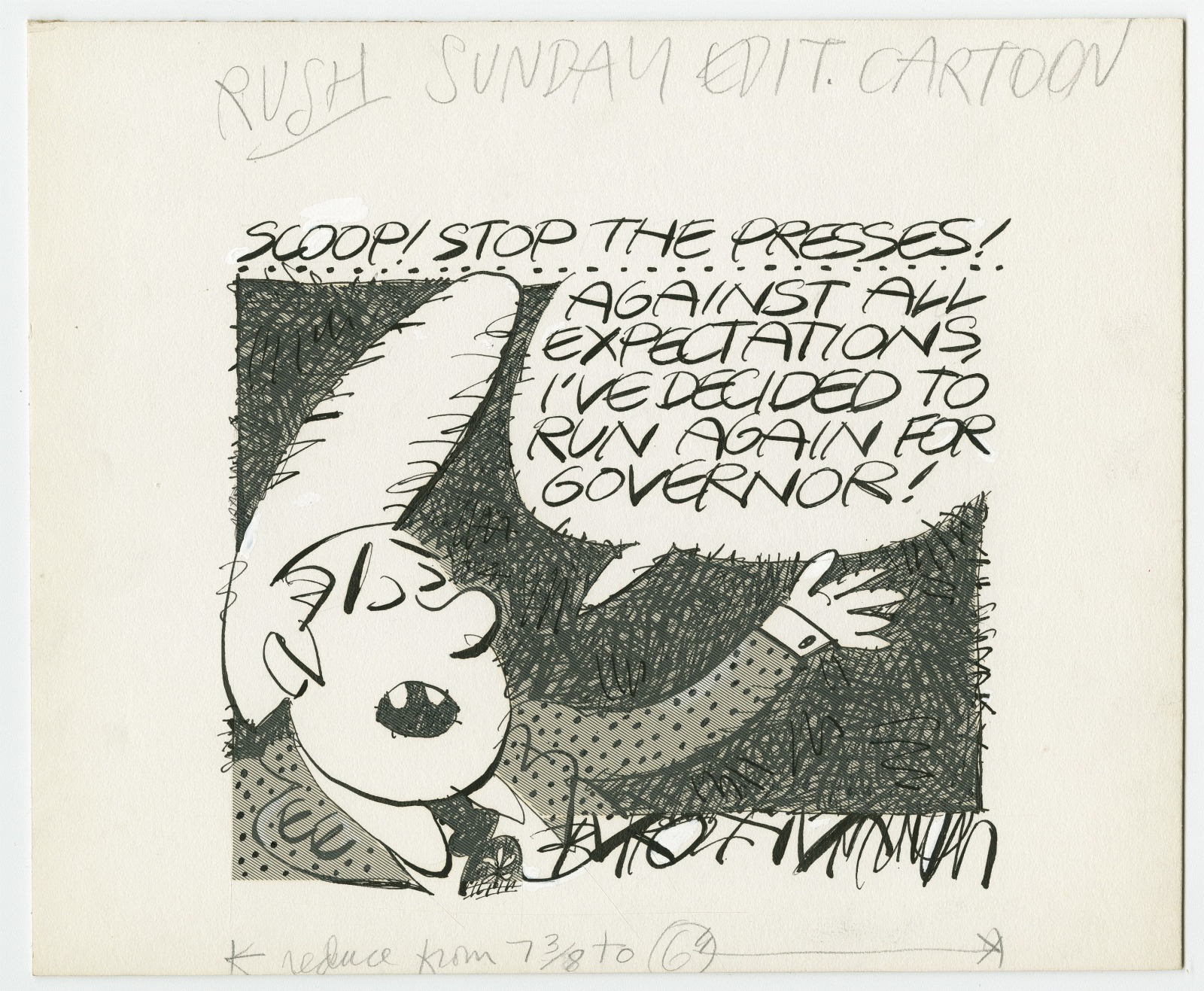

A political cartoon by Byron Humphries lampoons the alleged uncertainty around Edwards’ decision to run for the governorship in 1981. The Historic New Orleans Collection.

By most accounts, Louisiana’s open election process performed well in its first test in the fall of 1975. There were few surprises. Governor Edwards, who many claimed pushed the open election law principally to benefit himself, cruised to reelection, securing 62 percent of the popular vote. His next closest challenger, Democrat Robert Jones, garnered 24 percent of the total. Louisianans grew accustomed to their unique election system, which confusingly became known as an “open primary” despite this term more aptly describing a process in which party primaries are open to all voters regardless of partisan affiliation. In Louisiana the term “majority vote primary” (often referred to as a “jungle primary”) proved a more accurate designation for the state’s system. Anyone who met the necessary requirements for candidacy could run for state office with majority rule ultimately determining the outcome. In a jungle primary election in Louisiana, any candidate who garners a simple majority—50 percent plus one vote—wins outright, or the top two finishers faceoff, pitting against each other two Democrats, two Republicans, or a Democrat and a Republican. Depending on the candidates and issues at stake, strange and unanticipated matchups can happen—and sometimes do.

In 1991 the nation watched in horror as Edwin Edwards, seeking a fourth term as governor despite an array of legal troubles, faced a gubernatorial runoff with former Ku Klux Klansman David Duke. Duke’s candidacy clearly benefitted from the open system in which the electorate split its votes between a large field of candidates. In the famous “crook vs. Klansman” election, Edwards won handily in the general contest with many Republicans voting Democrat to save the party—and state—from embarrassment.

A bumper sticker supporting Edwards against Duke in the 1991 gubernatorial election. Gift of Mrs. Jan White Brantley, The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Louisiana’s open system has also faced numerous legal challenges that forced change to state elections. In 1997 the Supreme Court ruled that all state-wide elections for members of Congress needed to take place on the same day. By this point Louisiana typically hosted its “primary” election in congressional races in October and thus certified victors when a candidate secured a simple majority in advance of the federally proposed November date. As a result of the ruling, Louisiana federal elections that require a runoff are now decided in December, later than those in the rest of the nation. In 2006 Governor Kathleen Blanco signed a bill into law that closed Louisiana’s 2008 congressional primaries, briefly restoring the old system of closed party primaries, only to have state legislators in 2010 reverse course and return congressional races to the open system. Tinkering with the Louisiana election system has occurred frequently, but the changes have focused on peripheral considerations, such as the specific date to hold elections. The essence of Edwin Edwards’s open system has stood the test of time.

Presently, in odd number years, elections for state offices are held in October with the runoff in November if necessary. In even number years, the first contest is slated for November with the runoff in December. In 2023 therefore, the contest to pick the successor to Governor John Bel Edwards (no relation to Edwin Edwards) is scheduled for Saturday, October 14, with the general election, if needed, slotted for Saturday, November 18.

Today there remains considerable interest in Louisiana’s peculiar election system and its place in national politics. Its fervent devotees remain on guard to derail efforts to alter its basic design. Its supporters prove legion, from those who view the system as strengthening their respective party’s power to those who claim it is the most democratic election system in the nation because it frees the people from the shackles of party bosses. Regardless of where one stands on the future of the current system, one thing is certain: while it remains in place, the voters of Louisiana are always one quirky election removed from an exhilarating political ride. Edwin Edwards, who brought the state much entertainment and turmoil while in public office, would no doubt be pleased by the continued popularity of his creation.

Keith M. Finley is associate professor of history and assistant director of the Center for Southeast Louisiana Studies at Southeastern Louisiana University. He is the author of the award-winning book Delaying the Dream: Southern Senators and the Fight Against Civil Rights, 1938–1965, as well as of numerous articles on Louisiana and southern history.