“You Smell Like a Garbage Can!”

The raw, raucous blues of Boogie Bill Webb

Published: March 1, 2021

Last Updated: June 8, 2021

Nick Spitzer

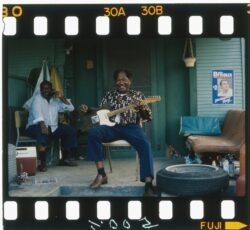

Webb on the porch with a friend.

I met Bill via Dawn Griffin, a producer at Jazz Fest, who asked me to put a band together for him. Bill was long out of the loop of hiring musicians himself. He’d never pursued a full-time musical career. He worked as a longshoreman and also repaired small engines with great skill, earning him the nickname, in his neighborhood, of “the lawnmower king.” That neighborhood was the Lower Ninth Ward, the home turf of Fats Domino, the Lastie family, and many other prominent practitioners of New Orleans’s rich musical traditions.

But Boogie Bill Webb played very few songs from the classic Crescent City canon. He focused, rather, on a rural style more typical of Mississippi, where he was born in 1924. As a child, Bill had learned at the feet of the blues-guitar master Tommy Johnson, acknowledging Johnson as “the reason I’m making this noise today.” Bill’s mother used to hire Johnson to come to New Orleans to play at fish fries. She’d split the profits with him, and they might make thirty-five dollars each. In stark contrast, a rare 78 rpm record by Johnson, originally released in 1930, sold on eBay for $37,100 in 2013.

When I met Bill Webb he stood among the last musicians to reprise Tommy Johnson’s archaic songs as a direct disciple, rather than a studied revivalist. One of those songs was “Canned Heat Blues”; during Prohibition, some people who craved alcohol—Johnson included—would recklessly ingest this toxic source of portable flame to get their high. Bill’s diverse repertoire also included vaudeville songs, jug-band music, ’50s blues standards, ’70s soul-music classics, ’80s blues hits, country songs, and the recitations known as “toasts” in African American oral tradition. One such declamation turned various brand names of whiskey into fictional characters: “Old Grand-Dad was so full of Ancient Age . . . I. W. Harper told Old Quaker to tell Hiram Walker let’s get Haig and Haig. Bring them down to Yellowstone Gardens that’s located behind the Town Tavern. There was a party the other night at the Old Log Cabin, wasn’t no music except Old Drum and nobody could beat him . . .”

And then there was Bill’s signature tune, an ode to personal hygiene entitled “Drinkin’ & Stinkin’”: “You smell like a garbage can, late at night, if I tell you what you been doin’ it make you want to fight . . . you don’t never want to brush your teeth but you always want to be up in my face . . . you’ve been drinkin’, pretty baby, and stinkin’ all night long!” Bill explained that this original composition described a woman “who had been wearing the same clothes for five or six days.”

To put a band together for Bill’s debut at Jazz Fest, I called Reggie Scanlan, the bass player for the popular rock band The Radiators, who’d previously worked with both Professor Longhair and James Booker. Reggie and I quickly discovered that Bill was an extreme time-jumper. Most blues songs have a twelve-bar song structure. But Bill might clip one verse to eleven and three-eighths bars and extend the next one to thirteen and two-thirds, or some other bizarre fraction which always differed. He simply dropped or added beats, and chords, at random. Our job was to adapt instantaneously and make his music sound seamless. We considered this an enjoyable challenge, and Bill loved our sometimes-psychic accompaniment. “Them boys can play,” he once said; “they just gifted to know what I’m going to do.” Such adjustment was easier for me, as a drummer, than for Reggie, who had to jump with both the beat and the chord changes. No wonder Bill called him “the maestro.” Jumping time does not mean that someone is playing or singing wrong, or badly; it’s just a different conceptual approach. In New Orleans, the popular blues artists Little Freddie King and Guitar Lightnin’ Lee personify this practice today. On the national celebrity level, Willie Nelson is very prone to time-jumping, on his vocals and guitar solos alike.

After Bill’s well-received set at Jazz Fest led to performances around the United States, the next logical step was to produce his first full album. Bill had recorded minimally in the ’50s and ’60s, with a few numbers reissued on anthologies. But this meager output barely hinted at his stylistic breadth. The thirteen songs we recorded came close to covering the entire gamut. Drinkin’ & Stinkin’ was co-released in 1989 by Flying Fish Records and the state-funded Louisiana Folklife Program. The album package was augmented with an in-depth scholarly essay by Nick Spitzer, then a folklorist with the Smithsonian Institution, now the host of public radio’s American Routes and a professor of anthropology at Tulane. In addition, the eminent music journalist Robert Palmer contributed succinct, insightful liner notes.

Some laudatory reviews followed. “Few blues albums are as much fun as this, or stamped with the full force of an artist’s personality,” wrote journalist/musician Cub Koda. Koda added that Bill was “one of the most idiosyncratic artists I’ve ever heard, an unlikely repository of all kinds of music,” duly noted that “Webb jumps time about every three and one-quarters bars,” and praised one song, “Love Me ‘Cause I Love My Baby So,” as “so structurally odd in its meter that it almost qualifies as abstract art.” But some people perceived the album as an offensive celebration of alcoholism, funded at the taxpayers’ expense. A newspaper in North Louisiana fumed, “What do we need with an agency that promotes Drinkin’ and Stinkin’?”—failing to grasp that the song ridicules drunkenness instead of encouraging it.

Bill played his last show in Holland in 1989, alongside some of the biggest names in blues. This ended his career on a high note, as he passed away the following year. I miss Bill. And I like to think that, somewhere in the ether, he is blithely confounding accompanists who expect him to play anything the same way twice.

Ben Sandmel is a New Orleans–based drummer, folklorist, producer, and the author of Ernie K-Doe: The R&B Emperor of New Orleans. In May 2018, the LEH honored Sandmel with an award for his Lifetime Contributions to the Humanities. In January 2020 the Folk Alliance International honored Sandmel with a Spirit of Folk Award.