Magazine

Zachary Richard: Musician, Poet, and Statesman

The 2016 Humanist of the Year sits down with Michael Martin for an interview

Published: March 1, 2016

Last Updated: April 30, 2019

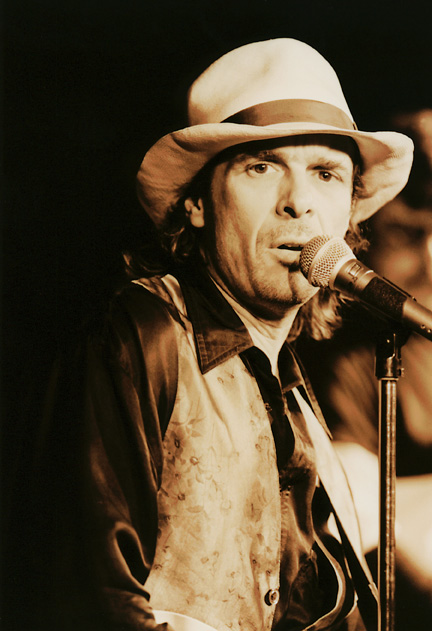

Courtesy of Zachary Richard, photo by Claude Dufresne

Richard performing at the Théâtre Outremont in Montreal, 2008.

Richard’s creativity and commitment to the French language and culture of Louisiana been recognized by numerous accolades. In 2013 the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, CODOFIL and the Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism appointed him as the first Poète lauréat de la Louisiane française. He holds honorary degrees from the University of Moncton, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Ste. Anne’s University and the Univeristy of Ottowa; is an Officier de l’Ordre des Arts et Lettres de la République Française; and is a member of the Ordre des Francophones d’Amérique, as well as an honorary member of the Order of Canada, one of the few Americans to receive Canada’s highest civilian award. In 2015 he joined with the State Library of Louisiana to launch a touring exhibition of an original copy of Les Cenelles, the first collection of poetry by African-Americans in the history of the United States, published in New Orleans in 1845.

Despite the accolades, Richard is soft-spoken, given to careful consideration and measured, thoughtful responses. His demeanor belies firm convictions about his art, his activism, and how those things combine. The following is excerpted from a conversation we had after Richard was named the 2016 Humanist of the Year by Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities.

Like so many of the baby-boomer generation, the social, cultural, and political upheavals of the 1960s had a deep effect on Richard.

I was raised in a very typical Americanized Cajun family. My parents’ ambition for me was that I become a doctor or a lawyer or something of that ilk…. When I discovered the counter-culture [as a student at Tulane University]—this was the Woodstock generation, the Vietnam War—all of those things had a very, very significant impact on my social and personal philosophy. I began to write songs and to write poems in 1968.

The influences were typical. On the side of poetry it was Allen Ginsburg and Gary Snyder and Jack Kerouac, and on the musical side it was everybody else—from Bob Dylan to Neil Young to Joni Mitchell to Leonard Cohen.… To the great dismay of my parents, I decided that I was going to move to New York and become a recording artist—I had no idea how that was going to happen. But I moved to New York, and I got a record contract with Elektra.

I was 21 years old and I had a recording contract and I never wanted to do anything else. It happened early enough in my life that I didn’t doubt that I could do it. When I was in my twenties, I don’t think anything would’ve stopped me. I didn’t make money for 10 years, and I slept on people’s floors and was basically a vagabond. But all I wanted was to write songs…to play music.

Richard’s music evolved during the early 1970s from straightforward American singer-songwriter fare to a style that encompassed traditional Louisiana music. The shift brought him wide recognition in Canada, where he lived from 1976 to 1980.

My first album was recorded in 1972. It didn’t come out for 20 years…. [But] the money that I got from that recording contract allowed me to buy some electric guitars and a Cajun accordion. I didn’t know about playing Cajun music. I wasn’t raised in a musical family. My parents liked big band swing—that was their musical style. So I didn’t hear Cajun music in the house. But when I got the recording contract, I started to sift around and discovered this incredible musical heritage. This was the early ‘70s, and it was back to the roots…

So I started playing the accordion and tried to integrate the Cajun heritage into my musical style…. I went to France in 1973 for the first time, and it was very disconcerting because I’d play the accordion and people would go crazy, and then I’d put the accordion down and pick up my guitar and play some original music and people would turn and walk away. So I had this sort of epiphany. And then I began to write in French—or translate some of my English songs into French, which is the way I began to write in French.

“One time someone said to me “You’ll never be able to bring it back like it was,” and I said “I’m not interested in bring it back like it was. I want to go forward with this.”

Then in 1974, we went to Québec for the first time, and that was really exciting. I was 23 years old, and I was suddenly propelled into the Québecois star system…. It was very interesting because I was perceived as being Québecois because I was singing in French. Québec and Louisiana have a long, long history, which remains part of the social memory of Québec. “Louisiana” is a word that means “cousin,” to Québecois—it’s something that is of the family, not close family, but the extended family. So I was able to find a place in the musical scene that was unique and just made for me.

Richard’s songs and poetry consistently tackle difficult issues confronting Louisiana—cultural loss and assimilation, environmental degradation, language suppression—and he is very much an activist in these matters and others. Yet he takes great pains to separate his craft from his activism.

I’ve never attempted to serve any cause—or make a statement—through my music… What I try to do is to express emotion.

I guess probably the first ‘political’ song I wrote would be ‘Réveille,’ which was composed in 1973…. I’d just read Dudley LeBlanc’s The Acadian Miracle and I was becoming aware of the details of the history of the Acadians, which nobody had ever taught me and nobody knew anything about in my family…. I was literally driving down the road when that song arrived—it just came out, and it was finished in the three minutes it took to sing. I had to rush home and write it down.

It was a very spontaneous creative process. It was not about saying something to influence; it was about expressing an emotion that was powerful.

I’ve always felt that if the songs have some sort of political or social impact, that’s lagniappe. I don’t sit down and say, “Oh, today I’m going to sing a song about the oil spill” or “Today, I’m going to sing a song about the suppression of French in school” or “Today, I’m going to sing a song about the natural environment and the loss of the wetlands.” Those things—that’s who I am—those things touch me. So when I look for stuff to say that means something, because songs have to mean something, [some songs end up with] more social import, but that has never been for me an objective…. It happens, and I’m very, very pleased and proud that it does happen, but I will not subjugate my creativity to a cause, no matter how much I espouse the cause.

I’m a citizen. I pay taxes, I live in a democracy, I can say pretty much what I want most of the time, and some things concern me a lot, like the natural environment and the French language, the situation of the French culture—not only just the French culture but the culture of southwest Louisiana—because I love these things. And I think all activism comes from love, basically, because if you’re going to go through all of the shit that is involved with becoming politically and socially committed, then you have to love the thing you’re trying to defend…

So the songwriter is basically prey to his emotions, and the activist is somebody who is prepared to express a point of view that hopefully will have a beneficial effect on the way people think or feel about particular issues or a particular situation. They’re two different parts of my experience, and I don’t put one to the service of the other.

With his parents Marie-Pauline and Eddie Richard, 1957. Courtesy of Zachary Richard

As stated, Richard’s activism focuses especially on two main issues today: the growing environmental threat to the state in the wake of climate change and the revival of the French language through immersion programs in Louisiana schools.

But his opinions on climate change and its effect on Louisiana are particularly blunt.

I try to separate the positive from the negative, but I’m basically a tree-hugging pinko, and in a red state with a lot of Tea Party people, it sometimes gets to be really frustrating—not so much because I think people are cruel or mean. It’s just that there’s a point of view which is, I think, basically ignorant, in the classical sense…they just don’t know what the consequences are of certain actions.

And that’s especially disturbing in terms of the environment, because we live at sea level, you know? And the general consensus is that by the end of the century, the sea level will have risen as much as two meters… A six-foot rise in sea level means that New Orleans and south Louisiana don’t exist. We’ll be underwater. And to pretend that global warming somehow doesn’t exist or that it’s just a figment of somebody’s imagination is to really fly in the face of scientific evidence, which is massively conclusive…

The thing that’s frustrating is that, with all of the engineering ability and all of the real competence that we have in the oil patch…it seems like we, South Louisiana, should be putting that to the service of alternative energy as opposed to sticking in the rut of oil and gas… We are an energy-driven economy, but the mule that we’ve hitched our wagon to is getting really tired, and pretty soon he’s going to fall down dead. Then what do we do?

I have a lot of friends in the oil and gas business, and they are not stupid people. They understand. But the economic dynamics seem to be very difficult to resist. And I don’t think it’s a Louisiana problem: I think it’s a world problem, it’s a United States, a capitalism problem. As long as there’s money to be made, somebody’s going to want to make it. And as long as oil is cheaper than solar power, nobody’s going to want to buy solar power. And that just seems to be the bottom line of the whole situation.

But it seems like, in this state in particular, we should have the political will and the intelligence and the foresight to be developing alternative sources of energy so that when push comes to shove, we can be on the right end of the big stick…otherwise we’re going to get beaten on the head.

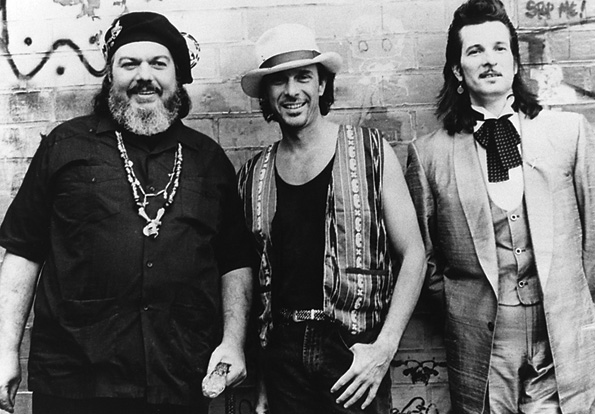

New Orleans Review with Dr. John and Willy DeVille, 1994. Courtesy of Zachary Richard

Richard’s powerful passion about French immersion education makes a compelling case for expanding the program in Louisiana.

We should put French immersion in every school in the state of Louisiana, because it’s going to allow our children to obtain an educational experience which is absolutely unique and also will prepare them for their future in a way that non-French, or non-bilingual, education cannot. The pedagogic benefits are so important that it’s just astounding to me that every superintendent of schools in the state of Louisiana isn’t fighting to make sure that all of their schools have it.

French education—and there’s Spanish immersion in Louisiana, there’s Chinese immersion in Louisiana—all of those work incredibly well to develop young students who are more capable of the grand old art of deduction. Deductive reasoning skills are enhanced significantly by foreign language immersion education.

The other thing is cultural. That’s the easy one. Alright, so we have this heritage that we need to celebrate…. And French—it’s like we’ve been given a gift. Our heritage has given us a possibility that otherwise we would not have.

We all share a common experience, which is enhanced by artistic expression and which can be celebrated most effectively through inclusion and tolerance.

One time someone said to me “You’ll never be able to bring it back like it was,” and I said “I’m not interested in bring it back like it was. I want to go forward with this.” We have this opportunity to use this tool to enhance, to enlighten, to educate our children, to really create a society which is not only well-educated but, also, open to the world.

My point is that we should not squander it. We should take advantage of it. There are three hundred million people that speak French in the world. That’s a huge market…. There’s something out there called La Francophonie, which is everywhere that people speak French. In that culture there is a tremendous appreciation of the language—and not only of the language but of the values, because French is not only the language that we speak but it’s also the language which gave us the Enlightenment. All of the notions of democratic society, freedom, equality, that we cherish were forged in France in the mid-18th century…

If you go into French immersion classes in the state of Louisiana, you’ll see people from around the world…from Acadie, Québec, France, Haiti, Africa—and that is probably the most beneficial aspect of the education. The educational advantages are undeniable, the cultural advantages are undeniable, but the humanist values are really, I think, the most important. Because you have kids that might have a teacher from Haiti or from Senegal or from Québec or from Acadie, so already you’re being introduced to another culture and another point of view.

Zachary Richard with Céline Dion, Quebec City, 2008. Courtesy of Zachary Richard

La Francophonie is based on inclusion, as opposed to exclusion. Especially in this time, we are in danger of becoming very closed-minded and bigoted and xenophobic—just look at some of the political discourse that’s going on today. We cannot abandon the principles upon which this country was founded out of fear. I think French immersion goes a long way to instilling in our young students an appreciation of other cultures, an openness and tolerance, which are, I think, the basis of an enlightened society.

Humanism is rooted in the idea that we are human beings. We’re all human beings, no matter where you’re from, what your skin color is, what religion you practice, or what language you speak. We all share a common experience, which is enhanced by artistic expression and which can be celebrated most effectively through inclusion and tolerance.

I think that needs to be said really loudly today.

—–

Michael S. Martin, Ph.D., is Cheryl Courrégé Burguières/Board of Regents Professor in History at the University of Louisiana Lafayette and director the Center for Louisiana Studies. He is the author of Russell Long: A Life in Politics (2014).