Latest

10 Fascinating Facts About the Civil War in Louisiana

Published: December 10, 2015

Last Updated: January 11, 2019

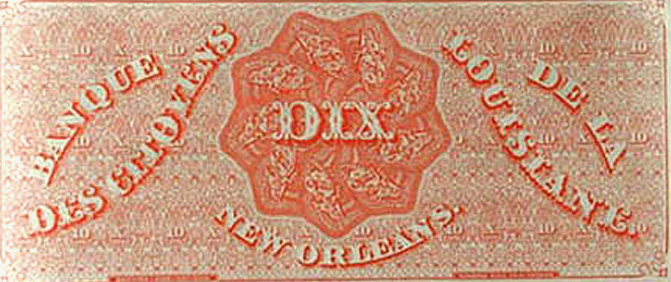

A dix note issued by the Banque de la Louisiane.

In the early 19th century, flatboatmen traveling down the Mississippi would sell their cargo in New Orleans in exchange for paper currency with the word “Dix” — French for the numeral 10 — issued by the Bank of Louisiana. Legend has it that the English-speaking men would return home with pockets full of what they called “Dixies” and eventually the region came to be known as “Dixieland.” Another theory credits the toponym’s provenance to the demarcation of Mason’s and Dixon’s line, drawn between 1763 and 1767 to resolve a border dispute between Pennsylvania, Maryland and Delaware. The song “Dixie” was written by a white Northerner, Daniel Decatur Emmett, and debuted at his minstrel show in New York City in 1859. The tune became an instant success and was quickly adopted as an anthem of the South. President Lincoln listed it among his favorites, even in wartime.

The Republican Party emerged as an abolitionist political force in response to the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The statute’s passage by Congress in 1854 violated the 1850 Missouri Compromise that was inteded to halt the spread of slavery above the 36° 30′ latitude as the U.S. expanded westward. Southerners were immediately disdainful of the emerging anti-slavery faction, so much so that in his presidential campaign Abraham Lincoln famously addressed the partisan friction in a speech at New York’s Cooper Union: “[W]hen you speak of us Republicans, you do so only to denounce us as reptiles, or, at the best, as no better than outlaws.” Louisiana did not recognize the Republican Party in the election of 1860 and Lincoln’s name was left off the ballots. By 1864 the state was partially under Union occupation. The thirteen reconstructed parishes cast Louisiana’s seven Electoral College votes for Lincoln, but Congress refused to count them since many legislators disapproved of Lincoln’s plans for readmitting the state to the Union.

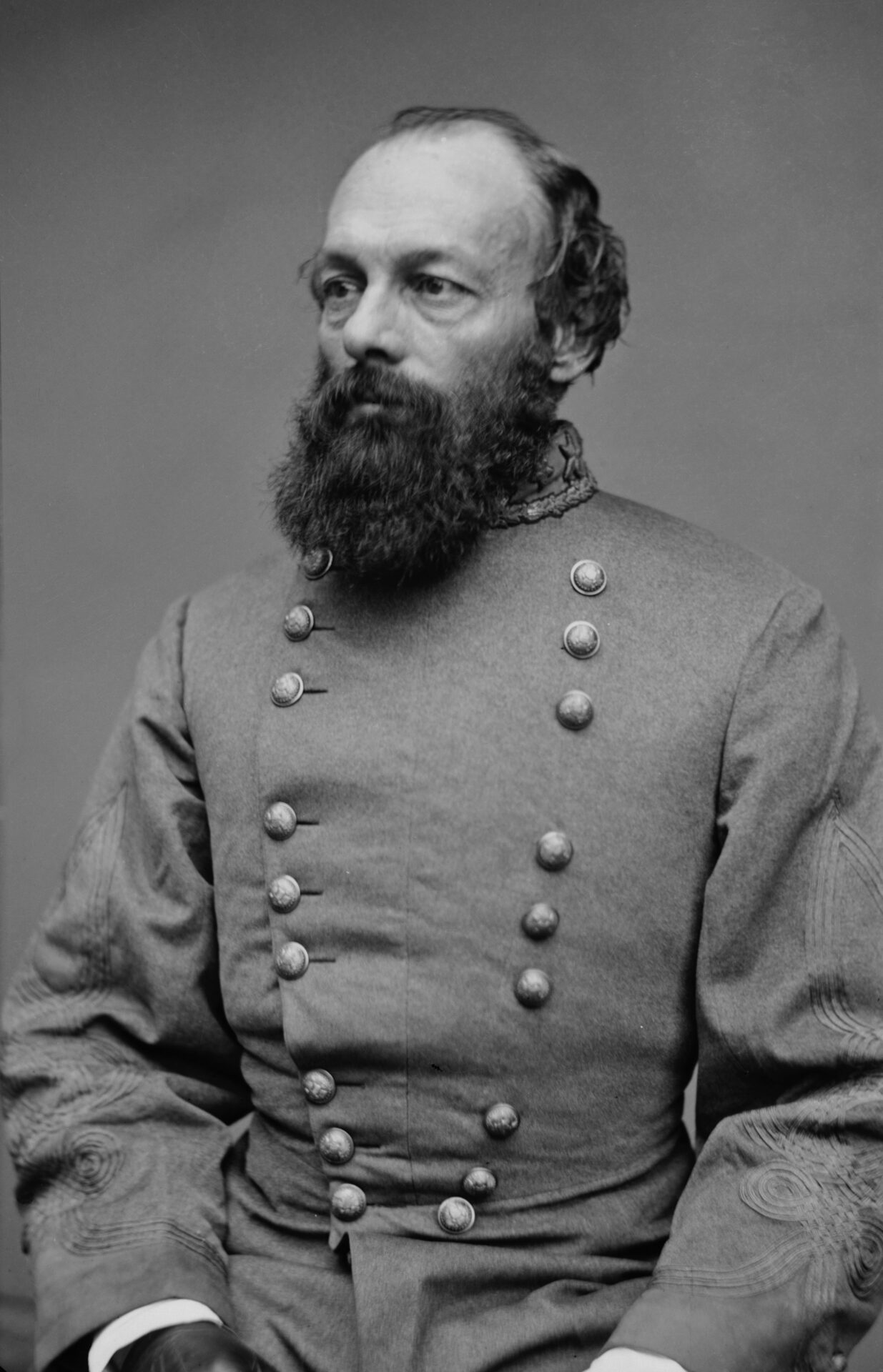

P.G.T. Beauregard was born in 1818 to a French-speaking family that owned a sugar plantation in St. Bernard Parish. He did not learn English until age 11 when he was sent away to boarding school in New York. He went on to graduate from West Point where he came to be nicknamed “Little Napoleon” (he stood 5 foot 7 inches tall). After rising through the ranks of the military, including leading troops in the Mexican-American War, Beauregard was offered the position of superintendent of his alma mater in 1861. Soon after he arrived at the U.S. Army’s academy on the Hudson River, Louisiana seceded from the Union. He was dismissed after only five days at his prestigious new post due to his vocal sympathies for the Southern cause. Confederate president Jefferson Davis appointed Beauregard as brigadier general and dispatched him to Charleston, South Carolina, where, on April 12, 1861, the newly minted CSA commander ordered artillery fire upon federal troops stationed at Fort Sumter, located on an island in the city’s harbor. Union soldiers surrendered the next day and Beauregard became one of the Confederacy’s first war heroes.

Lithograph of the Battle of Franklin, Tennessee, 1864, depicting the U.S. and Confederate battle flags.

Following the rebel victory at the first Battle of Manassas in July 21, 1861, General Beauregard noted that confusion had arisen among the combatants due to the similarities of the U.S. flag and the original Confederate flag, known as the “Stars and Bars.” A new square battle flag was proposed and approved featuring a blue X emblazoned with 13 five-pointed stars (representing each of the Confederate states) on a background of red. The banner known as the Army of Northern Virginia battle flag came to be the most widely recognized symbol of the Confederacy. In recent decades the contentious emblem has incited debate over its meaning: Southern pride and historical commemoration or racial oppression and defiance of integration and federal intervention?

Lieutenant Alexander H. Todd of the Confederacy’s First Kentucky Brigade was related to the first lady by way of her father’s second marriage. Two other half-brothers, David Todd and Samuel Todd, also took up arms against the North. During the Battle of Baton Rouge, Alexander Todd was mortally wounded in a friendly fire incident on August 5, 1862. He died two weeks later. Grief stricken from the deaths of sons Eddie and Willie — and later inconsolable following her husband’s assassination — Mary Todd Lincoln spent much of her time in consultation with spiritualists who claimed to communicate with the dead. In her letters, she wrote of supernatural encounters in the White House: “Willie lives. He comes to me every night and stands at the foot of the bed with the same sweet adorable smile he always had. He does not come alone. Little Eddie is sometimes with him, and twice he has come with our brother Alex.”

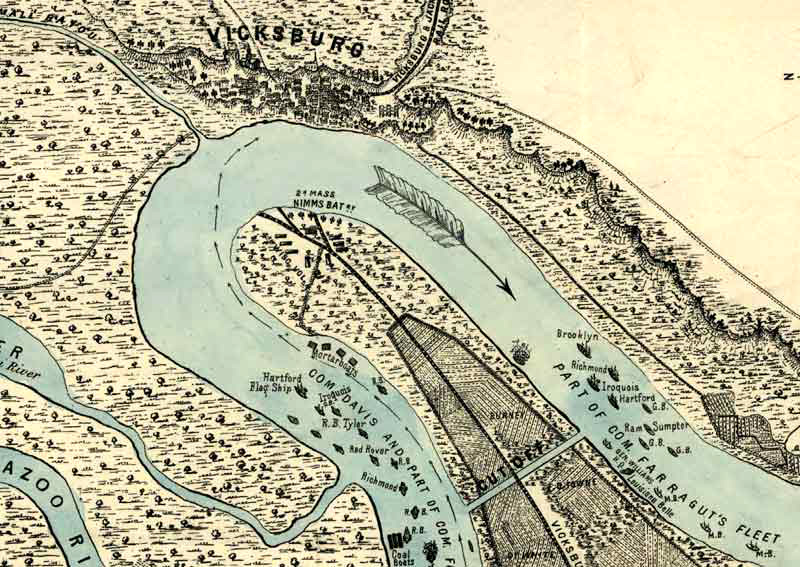

Following New Orleans’ surrender in April 1862 to Union naval forces, Major General Benjamin F. Butler was put in command of the city ahead of 10,000 occupation troops. The Massachusetts-born politician turned military leader ruled with an iron fist and was branded with the sobriquet “Beast.” On June 7, in spite of pleas from the the wife and children of prisoner William Mumford, Butler followed through on a military court order to hang the accused rabblerouser for tearing down the American flag from the New Orleans Mint and ripping it to shreds. Tempers flared, and at least one woman was known to have discarded the contents of a chamber pot upon the head of an officer from her second-floor window. Such brazenly disrespectful actions by women, including encouraging children to sing Confederate songs, spitting upon soldiers and turning backs to avoid acknowledging the military occupiers, prompted Butler to issue his infamous General Order No. 28. The edict read: “As the officers and soldiers of the United States have been subjected to repeated insults from the women, calling themselves ‘Ladies,’ of New Orleans, in return of the most scrupulous non-interference and courtesy on our part, it is ordered that hereafter when any female shall by word, gesture, or movement, insult or show contempt for any officer or private of the United States she shall be regarded and held liable to be treated as a woman of the town plying her vocation.” Profiting from the ensuing outrage, merchants in New Orleans began clandestine sales of chamber pots with Butler’s photograph pasted to the bottom. P. G. T. Beauregard had the Order read aloud to Confederate troops to stir emotions: “Men of the South! Shall our mothers, our wives, our daughters and our sisters, be thus outraged by the ruffianly soldiers of the North, to whom is given the right to treat, at their pleasure, the ladies of the South as common harlots? Arouse friends, and drive back from our soil, those infamous invaders of our homes and disturbers of our family ties.”

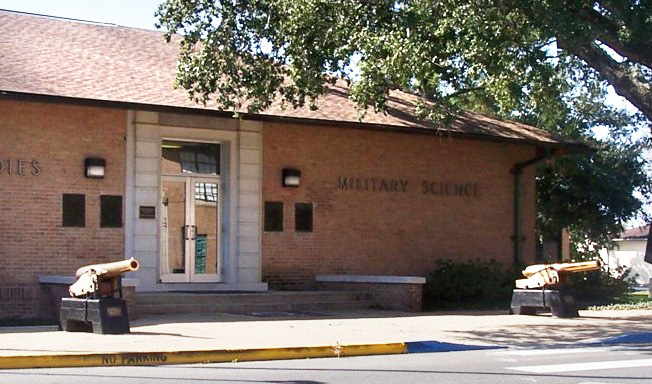

Two Civil War cannons that were used to fire upon Fort Sumter flank the entrance to the Military Science building at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. The cannons were donated to the university by Union General William Tecumseh Sherman, who served as the first superintendent of the academy that became LSU from 1859-1861.

Though General Robert E. Lee formally surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, on April 9, 1865, unconquered troops in in the far western stretches of the Confederacy held out hope of a last stand for months to follow. The Trans-Mississippi Department of the Confederate Army, headquartered in Shreveport under the command of General Edmund Kirby Smith, retained control of parts of Louisiana, Arkansas and Missouri, and all of Texas. By expanding their ranks, galvanizing Southern refugees who had fled from other states and relying upon the stored commodities and untapped natural resources of the Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), and the Arizona and New Mexico territories, there was a belief held by Confederate president Jefferson Davis and other defiant Southerners that a stronghold could be maintained that might allow the region some autonomy even in the face of defeat. Upon hearing news of Lee’s surrender, Smith had told his battle-weary soldiers, “With you rests the hope of our nation [the Confederate States] and upon your action rests the fate of our people … Prove to the world that your hearts have not failed in the hour of disaster, and that at the last moment you will sustain the holy cause which has been so gloriously battled for by your brethren east of the Mississippi.” By early June, Kirby’s desperate call to arms proved futile. He ratified terms of surrender that were drawn in Galveston, Texas, thus making Shreveport, the Confederate capital of Louisiana, the last Southern city to capitulate.