Magazine

Jordan Noble: Drummer, Soldier, Statesman

The incredible life of a marching music pioneer

Published: January 5, 2016

Last Updated: June 3, 2019

Courtesy of Louisiana State Museum, loaned by Gasper Cusachs, 00479.1

Historic drum used by Jordan Noble.

• • • •

In the 18th century it became custom in Europe and America to enlist drummer boys in the military. A practice of ambiguous morals, for some it allowed family to serve together, for many it was a badge of courage—an act of patriotism and duty—and for others the role served as a way out of poverty or slavery. Some viewed the practice critically as a form of child abuse. For U.S. war officials it widened their capacity to fill quotas. It fulfilled a military communication system requisite that freed others for fighting. This practice peaked during the Civil War and then on July 6, 1864, the U.S. War Department issued General Order No. 224, an “Act to regulate and provide for the enrolling and calling out the national forces” that set the age limit to 16. By the time of the Spanish American War in 1898, as the military modernized, the drummer’s roll became relegated to the parade ground, processions and ceremony.

Following the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, Louisiana became the 18th state to join the Union on April 30, 1812. The War of 1812 formally began in June and lasted until February 1815. In brief, the conflict settled property disputes between Britain and the United States in Canada and eased the way for U.S. empire building through domination and genocide of the Native Americans, the growth of the slave trade and westward expansion. A War Department General Order of March 19, 1813 divided the United States into nine military districts and New Orleans housed the headquarters of the Seventh District that included Louisiana, Tennessee, the Mississippi Territory and a year later the Creek Nation. The victory at the Battle of New Orleans helped establish the loyalty and importance of Louisiana to the rest of the country and it amplified Andrew Jackson’s military career, contributing to his election as president in 1828.

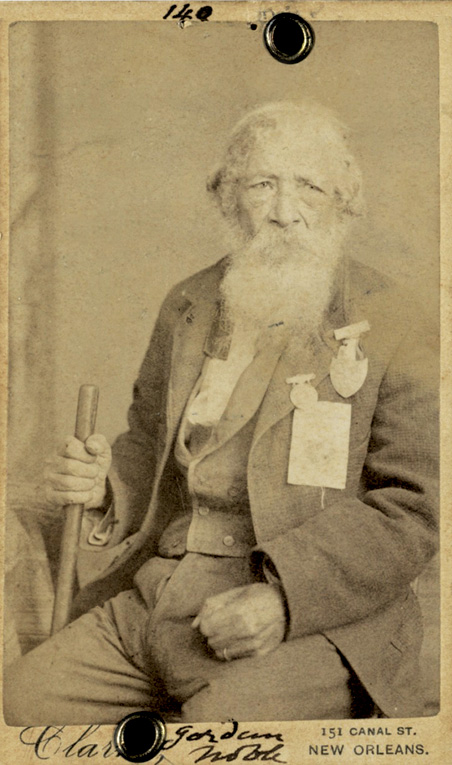

A postcard depicts an elderly Jordan Noble who, when he was age 14, played the drum for the 7th Infantry at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815. Courtesy of the Historic New orleans Collections, 58-101-l.3

After General Andrew Jackson’s forces overthrew the Creek Nation he was rewarded with a commission to Major General and appointed military commander of the 7th Military District on June 14, 1814. Following nearly two years on the warpath, Jackson arrived in New Orleans on December 1, 1814, to plan and bolster the city’s defense against a British attack. Major Arsènne LaCarrière Latour was appointed principal engineer of the 7th U.S. Military District on December 17, 1814. His Historical Memoir of the War in West Florida and Louisiana, 1814-15 published in 1816 is a rare contemporaneous narrative. Latour painted a dutiful and amiable picture of life in the city in anticipation of war.

“… The citizens were preparing for battle as cheerfully as if it had been a party of pleasure, each in his vernacular tongue singing songs of victory. The streets resounded with Yankee Doodle, the Marseilles [sic] Hymn, the Chant du Depart, and other musical airs, while those who had been long unaccustomed to military duty were furbishing their arms and accoutrements. Beauty applauded valour, and promised with her smiles to reward the soils of the brave. Though inhabiting an open town, not above ten leagues from the enemy, and never till now exposed to wars alarms, the fair sex of New Orleans was animated with the ardour of their defenders and with cheerful serenity at the sound of the drum …

“…The several corps of militia were constantly exercising from morning, till evening, and at all hours was heard the sound of drums, and of military bands of music. New Orleans wore the appearance of a camp; and the greatest cheerfulness and concord prevailed amongst all ranks and conditions of people….”

“Most of the men did not come from cities, and they had a hard time meshing with the population of New Orleans, who found the soldiers’ rough-hewn habits to be outside the boundaries of ‘acceptable society.’ … When it came to bathing, the soldiers often stripped naked and washed themselves in the Mississippi River.

Such were the circumstances young Jordan Noble resided in—but his time in New Orleans with the 7th Regiment prior to the conflict presented other experiences. John McManus in his history of the 7th Regiment, American Courage, American Carnage, wrote:

“Most of the men did not come from cities, and they had a hard time meshing with the population of New Orleans, who found the soldiers’ rough-hewn habits to be outside the boundaries of ‘acceptable society.’ Particularly distasteful was the soldiers’ tendency to urinate in public—everywhere and anywhere. … When it came to bathing, the soldiers often stripped naked and washed themselves in the Mississippi River. The local New Orleans belles who witnessed this brand of hygiene maintenance complained loudly to the regiment’s officers, who dutifully issued an order to stop bathing naked in the river.”

“Many soldiers could not resist the temptations of liquor, women and trouble in New Orleans. This led to a sharp rise in court-martials. One sergeant was charged with ‘being drunk’ [another for bedding an Indian woman named Toky in the barracks] … Collectively, the men of the 7th got into plenty of mischief. If they wanted something (usually liquor) they went after it, regardless of the consequences. They could be a handful to discipline and train in garrison setting, but they were tough soldiers when battle called.”

And called they were on December 23 when General Jackson learned the British forces had landed and were advancing towards the city he issued the order for a surprise counter attack. Jackson described the march to meet the British that included the 7th Regiment and Jordan Noble.

“… The gay rapidity of the march, and the cheerful countenances of the officers and men, would have induced a belief that some festive entertainment, not the strife of battle, was the object to which they hastened with so much eagerness and hilarity. In the conflict that ensued, the same spirit was supported …”

African American historian Marcus Christian wrote of that day: “Following Coffee’s men was the United States 7th Regiment, its 14-year-old mulatto drummer-boy, Jordan B. Noble, beating away on the regimental drum. At eight o’clock [p.m.] when the fog became particularly heavy, it was this boy’s drum, rattling away in the thick of battle, ‘in the hottest hell of fire,’ that helped to serve as one of the guideposts for the fierce battling American troops.”

In this strategically important and violent clash that lasted around two hours, the outnumbered U.S. forces halted the approach of the British and allowed Jackson and his soldiers time to make camp and establish defenses. The official casualty count was the British 277 and the Americans 213 with hundreds wounded. The 7th Regiment lost seven men with twenty-eight wounded. The count included one British drummer dead and two missing.

In camp the full spectrum of human emotion was enhanced and surely at times irritated by the rat-a-tat-tat of a capable drummer. Most of the military units, whether U.S. regulars or militia, had their own drummer, and, following military code, the drummer signaled commands, each with a distinct rhythm pattern that the soldiers responded to accordingly. From the 23rd of December, through the decisive battle on January 8th and dismissal, the duty of drummers, including Noble, was to sound reveille to awaken soldiers; signal roll call and call officers to meeting with the command; assemble the regiment to drill and set the tempo and direction of the march; and to beat the retreat at sunset for roll call and orders. They would drum up the order for provisions such as food, water, wood and ammunition and drum out of camp any undesirables, including captured and court-martialed deserters by beating the tune of the “Rogue’s March.”

Equally important, the drummers along with military bands entertained the troops during down time. On occasion the drums were bid to taunt and terrorize the enemy. With young strong arms, Noble powerfully alerted the call to arms, the long roll of attack or a quick and definite retreat from fighting. At times of engagement drummers would help rally the troops, push their adrenaline level, raise their spirits and focus their thoughts of purpose and reason as they prepared to kill or be killed. Then later they’d beat the somber, muted and profound death rattle of the funeral march when burying the dead. This was heavy lifting for anyone—much less a 14-year-old and perhaps more than a teenaged drummer boy could fully comprehend.

Most of the military units, whether U.S. regulars or militia, had their own drummer, and, following military code, the drummer signaled commands, each with a distinct rhythm pattern that the soldiers responded to accordingly.

The famous tattoo, later known as “Taps,” was sounded at night usually when the troops were stationed in town. The term is derived from the Dutch military word “taptoe” to signal shutting off the beer taps or essentially the last call at the bar. Yet, as previously noted, some men of the 7th Regiment evidently ignored the tattoo.

Noble related that Drum Major Louis Roquer from Captain Fortune Penn’s Company encouraged him to enlist, perhaps, suggesting that Roquer tutored young Noble in the basic rudiments of drumming and military drum signals. Military records offer the anglicized name of Louis Raca or Racca as drum major of Penn’s Company.

In the book, A subaltern in America: Comprising a narrative of the campaigns of the British army … published in 1833 and attributed to G. R. Gleig, is a battlefield account dated December 31, 1814.

“… It was now about midnight … instead of a frost, a thick mist hung in the air which not only annoyed by the cold moisture which it threw upon us, but effectively hindered the stars …

“… About two hours before daybreak, however, a general stir took place in the American lines. It was their mustering time … and they did so to the sound of drums and trumpets, and other martial instruments. The effect of this warlike tumult as it broke in all at once upon the silence of night was remarkably fine. Nor did the matter end there. The reveille having ceased, and the different regiments having taken their ground, two or three tolerably full bands began to play, which continued to entertain both their own people and us till broad daylight came in. Being fond of music—particularly of the music of a military band, I crept forward beyond the sentries, for the purpose of listening to it. The airs which they played were some of them, spiritless enough—the Yankees are not famous for their good taste in anything—but one or two of the waltzes struck me as being peculiarly beautiful; the tune, however, which seemed to please themselves the most, was their national air known among us by the title of ‘Yankee Doodle,’ for they repeated it at least six times in the course of their practice. …

“The American camp, in short, exhibited at least as much as the pomp and circumstance of wars, as modern camps are accustomed to exhibit; and the spirits of its inmates were kept continually in a state of excitement by the bands of martial music.”

Military records show two bands were in camp. Both from New Orleans, one was attached to Plauche’s Battalion and the other to D’Aquin’s Company of free men of color. The latter included lead musician Luis Hazeur, a property owner near Metairie Ridge, and the grandfather of future musicians Lorenzo Tio, Sr. and Louis “Papa” Tio.

The Battle of New Orleans inspired the creation of numerous songs but little is known of the vernacular music performed in camp. Legend has it that celebratory fiddling inspired the creation of the song, “The Eighth of January,” whose melody was interpolated in the much later song, “The Battle of New Orleans,” written by Jimmy Driftwood and made into a hit by Johnny Horton in 1959.

The mural Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans, January 8, 1814, by Ethel Magafan, located at the Recorder of Deeds building in Washington, D.C., includes African Americans among troops under Jackson’s command. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

It is conceivable that on January 1, 1815 “Auld Lang Syne” was rendered and it is likely that “Hail Columbia” was frequently played. To this day, “The Girl I Left Behind Me,” is the official marching song of the U. S. 7th Regiment and regimental lore tells that it was adopted through the rite of conquest during this military campaign. The story goes that members of the 7th Regiment captured a British lookout while he was whistling the song and learned it from him. The Military Academy at West Point uses it still in the final parade before graduation. The song is of Irish derivation and a verse of one version is:

The hours sad I left a maid

A lingering farewell taking

Whose sighs and tears my steps delayed

I thought her heart was breaking

In hurried words her name I blest

I breathed the vows that bind me

And to my heart in anguish pressed

The girl I left behind me

The grenadiers (grenade handlers) attached to General John Baptiste Plauché’s Battalion of French Creoles sang as they marched:

Go forward Grenadiers

He who is dead requires no ration

Go forward Grenadiers

He who is dead requires no ration

After the war, veterans gathered annually above Tremoulet’s Cafe on the south side of the Place d’Armes to commemorate the victory of January 8th and sang this battle cry. In Clara Gottschalk Peterson’s “Creole Songs of New Orleans,” she noted that “Go Forward Grenadiers” was the inspiration for the opening of her brother Louis Gottschalk’s “Bananier.” The bass line of the first eight bars echoes the beat of a quickstep march.

In the early 1880s Jordan Noble briefly addressed his life and military career in three published reports: one in the Daily Picayune, another in the Washington, D.C.-based Vedette monthly and a final revision in the black-owned Weekly Louisianian. A short conversation with Edward Wharton of the Daily Picayune included, “I was in all the battles under General Jackson,” and Noble acknowledged that the General personally recognized him for his service. “’Lively times, Jordan,’ said [Wharton]. ‘Yes sir,’ he [Noble] replied; ‘and fine times for us; but’—and the old soldier’s eyes twinkled,—‘the British didn’t like ‘em.’ ”A troubling detail that Noble chose to sidestep was his own experiences in the wretched system of slavery. Documentation reveals that while slavery directly influenced his career path as a soldier and musician, he did not let it define who he was as a person, nor did he turn his back on those less fortunate than he. In 1882 Noble applied for and received a pension from the U.S. government as a veteran of the War of 1812. Admission of his enslavement would have eliminated his ability to receive this benefit.

Jordan Noble’s reputation as a hero of the Battle of New Orleans allowed him the freedom and mobility to pursue music and work…

Young Jourdan (later spelled Jordan) and his mother Judie (also referred to as Judith) first appear in the historic record in the fall of 1813. John Brandt owned property in East Baton Rouge and dealt in a sundry of goods from peas and beans, to muscatel and tobacco from a warehouse in New Orleans. On occasion he sold people, as on November 15, 1813, when he transacted the sale of Judie, a black woman age 30, and her seven-year-old black son Jourdan. This enslaved family of two came from owners in East Baton Rouge and sold for $550.00 to the Frenchman Jean G. Chaumette who had worked as supercargo on slave ships from Africa to the Gulf Coast and speculated in slave trade investments. Chaumette then sold Judith and Jordan to Lieutenant John Noble of the 7th Regiment on June 2, 1814.

The difference in age between what Noble claimed to be during the war (14) and was noted on the 1813 bill of sale (seven) was credibly the result of several motives: the most obvious being an aggressive sales tactic as a younger slave would be considered capable of offering a longer valuable service. Further, depriving knowledge of date of birth was one way slavers attempted to hold sway over their human property. In turn, freed people and those born outside bureaucratic customs, well into the 20th century, gained latitude and advantage by claiming their age on an as-needed basis. Jordan, during his life, gave four different birth dates on four different documents, the earliest being 1796 and the latest 1804, before settling on the year 1800 later in life.

Lieutenant John Noble, a native of North Carolina, most likely shared the workload of Judie and Jordan with fellow officers of the 7th Regiment as his purchase defied U.S. military regulations. Jordan received his last name from Lieutenant Noble and his battlefield heroics, as described by Marcus Christian, are supported by the report that Lieutenant John Noble and Major Alexander White, who later owned Jordan and his mother, were both severely wounded in the initial battle of December 23. Jordan’s distinguished middle name, Bankston, is Swedish for “by the bank” or “the mound” and could be the result of being stationed near the center of the breastworks along the Rodriguez canal during the time in camp and battle. Another result of the 7th Regiment’s location is their still current nickname, “The Cottonbalers,” in reference to bales of cotton temporarily used to fortify the breastworks.

In 1815 both Lieutenant Noble and Major White of the 7th Regiment were in the first group of veterans to receive benefits, including a pension and land allotment in Louisiana. Medically they were both classified as invalids. Major White was promoted to the rank of colonel to recognize his valor and to boost his veteran benefits. Before his death in 1817 John Noble sold Judith and Jordan to retired Colonel White. Following the death of his wife Elizabeth in 1821, Colonel White fell into deep poverty. In turn he was forced to liquidate his property at a sheriff’s sale in 1823, at which time John Reed purchased Jordan and his mother.

This proved a godsend for Jordan and Judith. Reed was a seaman who owned a transport ship. He was also a musician and a veteran of the U.S. military. He was a native of Newport, Rhode Island. In 1804 he applied for and received in New Orleans a “U.S. Seamen’s Protective Certificate.” He served as a musician under the command of General Wilkinson in Captain Hooke’s Company in New Orleans in 1807. Upon being transferred to Captain Pike’s Company (Captain Zebulon Pike of Fort Pike and Pike’s Peak fame), Reed deserted and under order of Wilkinson was captured, imprisoned, tried, convicted and punished with 50 lashes of the whip and then returned to prison.

Being a musician and coming from Rhode Island, where the first anti-slavery laws in the 13 colonies were enacted in the 1770s and a very early abolition society was formed in 1794, as well as having lived through the agony of receiving 50 lashes, Reed was a slave owner whose background suggests a capacity for compassion and empathy towards enslaved people in general, and compassion and Jordan Noble in particular.

Jordan’s reputation as a hero of the Battle of New Orleans, with support from John Reed, allowed him the freedom and mobility to pursue music and work, obtain an education, continue his military career and begin to raise a family. Documentation survives to suggest that Reed’s legal claim of ownership was more to protect Jordan from slavers than to capitalize on his labors.

Jordan’s reputation as a hero of the Battle of New Orleans, with support from John Reed, allowed him the freedom and mobility to pursue music and work, obtain an education, continue his military career and begin to raise a family. Documentation survives to suggest that Reed’s legal claim of ownership was more to protect Jordan from slavers than to capitalize on his labors.

Jordan Noble’s experiences in the 7th Regiment introduced him to music that was, along with his African ancestry, the basis of his profound contributions to music and parade traditions in New Orleans. It introduced him to a camaraderie and fellowship of respect beyond race and an experience of solidarity of purpose that carried him forward into an extraordinary life. His is the only appreciable career in music that spans and connects 1820s-era Congo Square to drumming demonstrations that he participated in alongside the Excelsior Brass Band at the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition in New Orleans in 1885. He died in 1890.

Within his life and legacy there is a face, a name and a record of a life well spent, drummed up from the bottom of a top-down society and echoed each time a young boy or girl picks up a stick and beats a rhythm, blows a horn or plucks a string.

—–

Jerry Brock is a filmmaker, Grammy Award winner, music researcher and co-founder of the WWOZ community radio station in New Orleans. This feature is drawn from his book in progress, Jordan Noble: New Orleans Drummer Extraordinaire.