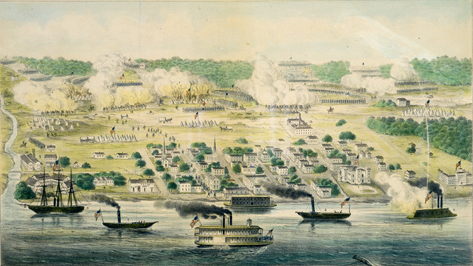

Battle of Baton Rouge (1862)

Union and Confederate troops fought to secure the strategic town on the Mississippi River.

The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Color reproduction of a hand-colored lithograph depicting the Battle of Baton Rouge.

When federal troops marched into New Orleans on May 1, 1862, they took control of the most important city in Louisiana and also one of the most important naval bases in the South, but that was only part of the Union strategy. The federal plan from early in the war was to blockade southern seaports and take control of the major rivers. This, Union planners thought, would starve the South into submission. By controlling the river, the Union could block the export of cotton, thereby eliminating a valuable source for revenue for the Confederacy. At the same time, Union forces could import supplies for themselves while denying Confederate access to food, medicine, and other supplies. Control of the Mississippi River, Union leaders knew, meant controlling the major cities and towns on the river—New Orleans, Donaldsonville, Baton Rouge—as well as the Confederate strongholds upriver from Baton Rouge at Port Hudson and at Vicksburg.

When Louisiana seceded from the Union in January 1861, state militiamen quickly took control of the Baton Rouge arsenal and ordnance depot (now know as the Pentagon Barracks) away from the federal government. Built on the east bank of the Mississippi River in Baton Rouge in 1816 and refurbished in 1838, the ordnance depot included an arsenal and barracks, making it strategically valuable to both sides. After securing the depot for the Confederacy, troops gradually left Baton Rouge when they were drawn into fighting elsewhere. As a result, Baton Rouge had few defenders in 1862, making the capital an appealing Union target.

Having secured New Orleans, part of Union Admiral David G. Farragut’s gunboat fleet headed up the Mississippi River. In response, members of the state’s Confederate government fled from Baton Rouge and established what they hoped to be a temporary capital in Opelousas. To prevent Union troops from capturing cotton and liquor, cotton bales were lined up along the Baton Rouge levee, doused with liquor, and set afire. “With mixed emotions,” one history notes, “planters and bartenders watched their commodities go up in smoke.”

On the evening of May 7, 1862, Union naval Commander James S. Palmer reached Baton Rouge aboard the gunboat USS Iroquois and demanded that the city and its 7,000 inhabitants surrender. Baton Rouge Mayor B. F. Bryan replied, “The city of Baton Rouge will not be surrendered voluntarily to any power on earth.” He acknowledged that the town was “entirely without any means of defense,” but insisted nonetheless that it would have to be taken “without the consent and against the wishes of the peaceable inhabitants.”

Palmer later reported to Farragut, who had remained in New Orleans, that he regarded the mayor’s “arrogant” reply as “nonsense,” and on May 12 “weighed anchor and steamed up abreast the arsenal, landed a force, took possession of the arsenal, barracks, and other public property of the United States, and hoisted over it [the Union] flag.” There was no resistance from the people of Baton Rouge. Nonetheless, Palmer sent a second note to the mayor to warn him “that [the Union] flag must remain unmolested, though I leave no force on shore to protect it. The rash act of some individual may cause your city to pay a bitter penalty.”

Farragut himself arrived later in the day aboard his flagship USS Hartford, and the first Union troops to reach the city, 1,500 men commanded by General Thomas Williams, arrived on the afternoon of May 13. Their ultimate destination was Vicksburg, but they did disembark from the steamers long enough to make a show of force by marching to the arsenal and back to the boats before continuing upriver the next morning.

The Recapture of Baton Rouge

It was a far different situation when the Union fleet reached Vicksburg. Some 8,000 Confederate troops rushed in to defend the town, putting heavy guns high on the bluffs overlooking the river. From that vantage point, the artillery could bombard any Union vessels trying to get to the city. Realizing that it would take more men and firepower than he had, Farragut ordered six boats to stay behind to block the river, then turned the Hartford and several other gunboats back to Baton Rouge.

When Farragut’s little fleet arrived in Baton Rouge on May 28, a band of about forty Confederate guerrillas fired on the Hartford’s chief engineer and four sailors as they rowed toward the Baton Rouge landing. In retaliation, Farragut ordered the Hartford and Kennebec to shell Baton Rouge. Only one person was killed, but several were wounded, and the damage to buildings near the river was extensive, particularly to the capitol building (now known as the Old State Capitol), the Harney House Hotel, and St. Joseph’s Catholic Church. Farragut made his point, but the incident also persuaded the Union commanders that the city could no longer be left unoccupied. General Williams and his troops returned to Baton Rouge on May 29, took over the ordnance depot, occupied the capitol, and pitched tents on its grounds. With Baton Rouge apparently secure, Farragut left two gunboats to support the troops holding the arsenal and went back to New Orleans. Shortly thereafter, General Williams took the bulk of his men back up the river for another try at Vicksburg, leaving a handful of troops in Baton Rouge.

The Battle of Baton Rouge

The second Union attempt at taking Vicksburg met with no more success than the first, and General Williams was ordered back to Baton Rouge in mid-July. The Union withdrawal freed Confederate troops at Vicksburg for other duties, and on July 27, Confederate General John C. Breckinridge marched south from Vicksburg with fewer than 4,000 men to drive the Union forces from Baton Rouge. At the same time, a small Confederate fleet led by the CSS ram boat Arkansas headed down the river to provide whatever help it could. To do that, the Arkansas ran through the Union blockade that Farragut had placed below Vicksburg, fighting a famous two-hour battle after which its commander, Lieutenant I. N. Brown, reported that the ram had done “much injury” to the Union fleet.

Meanwhile, Breckinridge moved by rail to Camp Moore in Tangipahoa Parish, marched his army to Greenwell Springs and then to Baton Rouge, where federal troops were concentrated along what is today Nineteenth Street, between Government Street and North Street. Breckinridge believed that the Union forces of 5,000 were much larger than his own of about 3,400 and that the Union troops were reinforced with three gunboats. He also knew that his own men were exhausted from fighting at Vicksburg. Breckinridge decided not to attack Baton Rouge until his forces could be protected from the fire of Union gunboats in the river.

When he was assured that the Arkansas would be at Baton Rouge by daylight of August 5, Breckinridge began to plan the Confederate attack. His troops arrived at the Comite River, ten miles from Baton Rouge, on the afternoon of Monday, August 4. With men dropping out all along the way because of heat and illness, they reached the outskirts of the capital a little after midnight on the morning of August 5. Breckinridge estimated that, because of all the illness, he entered the Battle of Baton Rouge with no more than 2,600 men.

The Confederate force included regiments from Louisiana, Mississippi, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Alabama, divided into two divisions. Brigadier General Charles Clark commanded the First Division, which was positioned on the Confederate right on the north side of Greenwell Springs Road. Brigadier General Daniel Ruggles commanded the Second Division, assembled on the south side of the road. On the Union side, General Williams commanded troops from Connecticut, Indiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Vermont, and Wisconsin, who took defensive positions with their backs to the river. While the Union appeared to have a numerical advantage, practically none of Williams’s troops had ever been in battle before. The Confederate forces, in contrast, were mostly veterans of the major battle at Shiloh in southwestern Tennessee. More recently, many had been involved in the defense of Vicksburg the previous month.

The Confederates attacked at dawn along Greenwell Springs Road. While troops on the Confederate left fought to within a mile of the river, those on the Confederate right moved down Plank Road to Bayou Sara Road and fought the Union troops there. The Union commander, General Williams, was killed as Confederate forces steadily gained the advantage during six hours of fighting. But the success of the Confederate troops also led to their undoing. As the attackers pushed forward, Colonel Thomas Cahill, who took command upon Williams’s death, moved the Union troops back closer and closer to the river, so that fire from federal gunboats was able to reach the Confederate lines.

The Union boats were unchallenged; the Confederate boat Arkansas had not made it to the fight as planned. Though Breckinridge did not know it at the time, it was never going to arrive. After running through the Union blockade at Vicksburg, Lieutenant Brown, the commander of the Arkansas, took several days of leave but, before going, told his superiors that the boat’s engines badly needed repair. Nonetheless, it was ordered downriver to Baton Rouge under command of its executive officer Lieutenant Henry K. Stevens. The engines did break down several times between Vicksburg and Baton Rouge. Even though the engineer was able to get them running again each time, it was clear that they were not reliable.

The Arkansas was able to get within four miles of Baton Rouge, but both of its engines failed just as it was preparing to fight the Union gunboat Essex. The Confederate vessel drifted helplessly to the shore. The Arkansas’s guns and men were put ashore and its commander set fire to the boat to keep it out of Union hands. It drifted down the river for a bit, finally blowing up when the fire reached the ship’s powder magazine. Deeming it unwise to “pursue the victory further,” Breckenridge withdrew his troops back to the Comite. A few days later, they moved up the Mississippi River to Port Hudson.

Meanwhile, the Union forces, fearing another Confederate attack, strengthened their position by blocking streets with felled trees. They also burned or destroyed the third of the town closest to the river, giving Union gunboats a clear shot at any advancing troops. Union Major General Benjamin Butler, who commanded all the federal troops in south Louisiana, first ordered Baton Rouge to be burned to the ground but later changed his mind. On the morning of August 21, the Union ground troops, after a spree of looting and wanton destruction, boarded transports and went back down the river to Carrollton, just above New Orleans. The gunboats Essex and No. 7 remained at Baton Rouge, and their commanders threatened to shell the town if Confederate troops came back. Ultimately, the Confederate troops inflicted 383 casualties in the Battle of Baton Rouge, but they suffered 456 themselves. One of the Confederate soldiers killed was Lieutenant A. H. Todd, half-brother of Mary Todd Lincoln, wife of President Abraham Lincoln.

The Burning of Donaldsonville

With the river cleared from the Gulf to Port Hudson, several miles above Baton Rouge, Union vessels began to use it at will and stood for no resistance from people on the shore. Donaldsonville, midway between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, was burned on August 9 after snipers fired on federal boats patrolling the river. Farragut told the people of Donaldsonville that the entire town would be destroyed if there was another incident and that the Union forces would “lay waste the whole neighboring coast,” a threat the committee said “he will assuredly carry into effect.” There was no more firing from Donaldsonville.

When Major General Nathaniel Banks replaced Benjamin Butler as commander of the Union forces in south Louisiana in December 1862, one of his first acts was to send some 8,000 to 10,000 Federal troops under General Cuvier Grover to reoccupy Baton Rouge. Three days after Christmas, the Union troops accidentally set fire to the gothic-style Old State Capitol and it burned to nothing but a shell. Federal troops occupied Baton Rouge for the rest of the war.