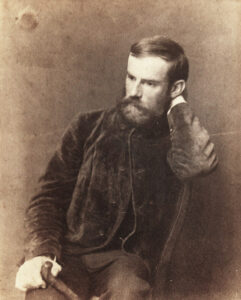

George Washington Cable

The writings of George Washington Cable explored the Creole culture and generated national attention.

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

George Washington Cable seated portrait. Cox, George C. (Photographer)

By the time he was forty years old, New Orleans native George Washington Cable was, as Michael Kreyling writes, as famous as any writer in America. He went on speaking tours with his good friend Samuel Clemens (better known as Mark Twain). His first book of stories had been favorably compared to the short fiction of Nathaniel Hawthorne, and his first novel, The Grandissimes, remained in print throughout his life. Although he continued to write a great deal, Cable’s reputation dwindled steadily, as did his fortune, during the latter half of his eighty-odd years of life. Cable’s decline stemmed, at least in part, from his unpopular critique of Southern race and class inequalities—a critique that earns Cable high praise from readers and critics today.

Early Life

Born on October 12, 1844, Cable was the son of George Washington Cable, Sr., and Rebecca Boardman Cable. Though born in New Orleans, Cable has always been thought of as an “outsider” in the city, perhaps because his mother was from Indiana and his father from Pennsylvania. His father was a wholesale merchant, buying goods off boats at the port of New Orleans and then selling them upriver. He also speculated in cotton and, at different times, owned interests in several steamboats. The family’s prosperity, however, was short-lived, as the booming New Orleans economy began to reel in the late 1840s from the effects of yellow fever, floods, and fluctuations in the price of cotton.

Cable served in the Confederate Army during the Civil War and was wounded. Returning to New Orleans after the war, he took a position as a cotton merchant’s bookkeeper. By 1870, he was writing a regular column in The New Orleans Picayune and soon thereafter accepted a commission from Scribner’s to write portraits of the postwar South for a national audience. In 1880, he published his first novel—and his single greatest work—the historical romance The Grandissimes.

The novel takes place in the immediate aftermath of the Louisiana Purchase and explores racial and class tensions in an aristocratic Creole family. A complex web of characters and subplots is held together, in part, by the story of Bras Coupe, a man who had been a prince in Africa but is working as a slave on a Spanish Creole plantation. Bras Coupe attacks his white overseer, and then flees into the swamps, chased by an angry mob, who catch him, cut off his ears, sever his hamstrings, and finally beat him to death. This vision of the brutal horror of slavery is at the center of Cable’s work, and accounts in large measure for his alienation from New Orleans society.

Critical Response

Cable was the subject of intense criticism in the mid-1880s by both Judge Charles Gayarré and the writer Grace King, the former insisting that his portrayal of the Creoles in The Grandissimes was nothing short of a “monstrous absurdity” and the latter suggesting that he wrote the novel merely to stab New Orleans in the back and please the Northern press. Cable’s history of New Orleans, The Creoles of Louisiana, drew much the same fire from those who preferred a whitewashed, romantic, and mythical vision of the city, which was increasingly marketable to tourists.

Cable continued to write, publishing Doctor Sevier, a novel about the plague in New Orleans, in 1884. But in 1885, after years of frequent visits to the North, Cable moved to Northampton, Massachusetts, where he increasingly focused on social reform and philanthropy. In the late 1880s, he wrote The Silent South and The Negro Question, two collections of essays critical of slavery and its legacy. These were followed by The Cavalier, a historical novel about the Civil War, in 1901.

Cable died in St. Petersburg, Florida, on January 31, 1925. Though his distinctly unpopular views on race led to a decrease in his popularity during his lifetime, Cable has been the subject of recent critical and popular interest. His analysis of race and class in The Grandissimes, in particular, now seems ahead of its time. Most of his letters and manuscripts are in the collections of New Orleans’ Tulane University.