Louisiana Purchase and Territorial Period

The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 added an immense, undefined amount of territory to the United States.

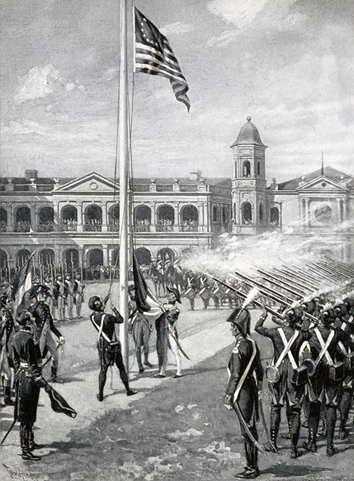

The Historic New Orleans Collection.

A black and white reproduction of a 1903 lithograph depicting a scene at Jackson Square after the transfer of Louisiana from France to the United States in 1803.

The period from 1803 to 1812 was a landmark in Louisiana history. In these years, the land that became Louisiana went from a European colony to a federal territory and finally to the eighteenth state in the union. In the midst of these political changes, Louisianians experienced social unrest, racial revolt, and international conflict. Meanwhile, determining what would become of Louisiana and its residents forced people in the United States and in Europe to consider what it meant to be American. Although Louisiana became a state in 1812, that hardly settled the questions unleashed by the Louisiana Purchase.

Acquiring and Defining Louisiana

Nothing reflected the tumult and uncertainty of early Louisiana more clearly than the battle over its borders. In April 1803, France ceded a vast but vaguely defined geographic space to the United States with the Louisiana Purchase. News of the acquisition came as an enormous surprise to the United States. President Thomas Jefferson had sought only New Orleans and access to the Gulf Coast. He now faced the challenge of governing far more territory and, even more daunting, a much larger and more diverse population. Further, the Louisiana Purchase treaty failed to specify clear borders, and it would be almost two decades before the United States had clear title to all of the land that now constitutes the state of Louisiana.

The boundaries of Louisiana took shape as a result of the political conflicts that gripped Europe and stretched across the Atlantic Ocean. These conflicts played out differently in the New World, as the United States exploited Napoleon’s invasion of Spain in 1807 and the subsequent crisis within the Spanish empire to seize West Florida in 1810. The Mexican struggle for independence also made Spain willing to make major territorial concessions in the West, even as the United States abandoned some of its own ambitions in Texas. It was not until 1819 that the Transcontinental Treaty finally established the eastern and western boundaries of Louisiana.

In the midst of these international conflicts, the federal government was also subdividing the land acquired through Louisiana Purchase into manageable political subdivisions. In 1804, Congress created the Territory of Orleans, which included much of the territory that now constitutes the state of Louisiana. Territorial rule was intended to provide a temporary system of government for the region and to prepare Louisiana for eventual statehood and jurisdictional equality alongside the other states of the union. The federal leadership appointed most major offices, while local residents were allowed to elect a territorial legislature. This system of territorial administration constituted a dramatic change from European imperial rule.

Many Louisianans complained about what they considered the slow progress toward statehood. Local residents demanded an increase in the number of elected offices and were particularly keen to see members of the old francophone community elected to those offices instead of the newly arrived Anglo-Americans. Despite these grievances, few sought a return to European rule, in large part because they believed the federal system offered far more benefits to its frontier settlements.

In the years immediately following the Louisiana Purchase, the federal leadership, officials in the Territory of Orleans, and local residents struggled to create the institutions that would make self-government within the federal system secure. In 1812, Congress approved Louisiana statehood, and President James Madison eagerly signed it into law. Statehood actually preceded the final determination of Louisiana’s borders, which underwent minor revisions until the Transcontinental Treaty finally established the boundaries once and for all.

Ethnic Relations

The Louisiana Purchase created confusing political circumstances within the Territory of Orleans. The treaty granted immediate citizenship to white Louisianans, who were eager to enjoy what they considered the rights of US citizenship. However, many people outside the territory claimed that the Louisianans did not know how to act as good Americans.

The political battle over Louisiana statehood often reflected the tense ethnic relations among white people within Louisiana. At the time of the Purchase, the territory’s white population consisted primarily of Creoles born in Louisiana, as well as migrants from Canada, the French Caribbean, and France itself. The vast majority of these people spoke French and considered themselves products of a French culture. At the same time, however, people had known more than thirty years of Spanish rule in Louisiana, and they had been joined by a sizeable population of Hispanic residents and Anglo-Americans. Equally important, many of them were deeply suspicious of the Napoleonic regime in France.

In these circumstances, Louisiana experienced complex and at times bewildering ethnic relations. The francophone (French-speaking) and anglophone (English-speaking) populations were often at odds. Meanwhile, the francophone majority created and preserved cultural institutions that made Louisiana unlike any other state in the union. French remained a common language in daily conversation and in official documents, and Louisiana’s legal system combined the Anglo-American common law with French, Spanish, and Roman principles of civil law.

At the same time, these differences were never so obvious as they now appear. First of all, there was no uniform francophone “community.” Creoles argued with French migrants, the residents of cosmopolitan New Orleans shared little with the residents of rural Louisiana, and French- and English-speaking residents often found common cause in their political and commercial pursuits. The notion of a Creole-American split eventually became the stuff of legend in Louisiana, but most observers were more struck by the absence of conflict or revolt.

The general amity among white residents depended in no small part on their commitment to racial supremacy. Whatever cultural or political disputes might divide white residents of Louisiana, they shared a belief in white superiority and a fear of non-white revolt. In the wake of the Louisiana Purchase, white people in Louisiana (regardless of ethnic background) came together to impose new restrictions on enslaved people and free people of color.

Non-white people responded accordingly. Enslaved men, women, and children repeatedly sought to run away and in 1811, more than eighty slaves owned by Manuel Andry in St. Charles and St. John the Baptist Parishes, launched an unsuccessful revolt along the German Coast that was the largest single slave uprising in the United States. Free people of color proved more successful. Located primarily in New Orleans, they sustained themselves as the largest, most prosperous free Black community anywhere in North America. Meanwhile, the white population supported the efforts of the federal government to undermine Native American sovereignty and, eventually, to force most Native Americans out of Louisiana. Native Americans developed numerous strategies of resistance but in the end proved largely unable to restrain the federal onslaught.

The War of 1812

The greatest test of Louisiana came during the War of 1812, when British troops invaded the Gulf Coast in 1814–1815. Louisiana militiamen defended the region ardently and demonstrated not only Louisiana’s commitment to remain in the United States, but also the ability of the United States to protect and support its newest state and its newest citizens. Meanwhile, enslaved people exploited the chaos to run away in large numbers, and some Native Americans allied themselves with Great Britain.

In the end, the Battle of New Orleans provided both white Louisianans and the federal leadership with an ideal opportunity to celebrate expansion and statehood. Free people of color and Native Americans who had fought alongside white soldiers also had the moment to prove their own loyalty to the United States. At the same time, the resistance of enslaved people and other Native Americans served as a reminder that the creation of Louisiana had expanded freedom for some while restricting it for others. These varied responses reflected the benefits as well as the challenges that faced people in an American Louisiana.