Cookbooks

Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, several Louisiana cookbooks collected the diverse cooking styles of Creole New Orleanians. Crescent City cookbooks continued to represent Louisiana throughout the next century.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

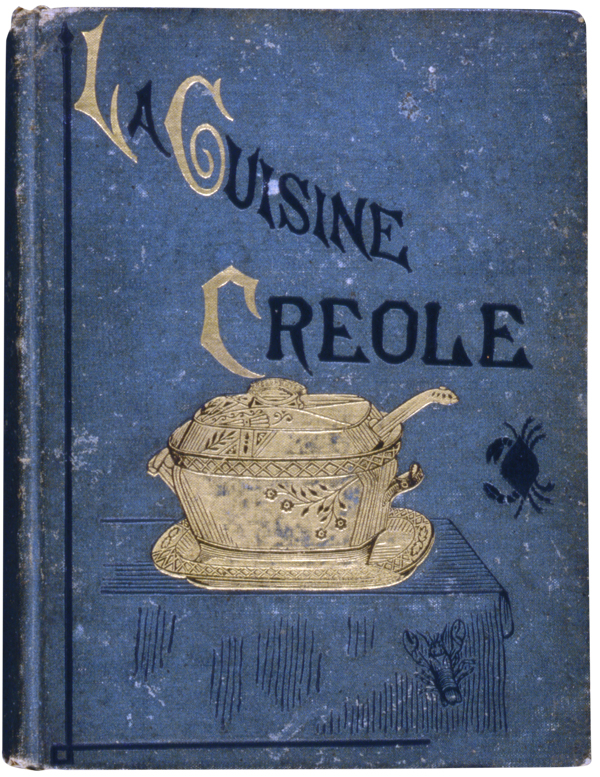

A color reproduction of the front cover of "La Cuisine Creole," by Lafcadio Hearn.

Perhaps no other state has inspired as many cookbooks as Louisiana. Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, several Louisiana cookbooks collected the diverse cooking styles of Creole New Orleanians, and Crescent City cookbooks continued to represent Louisiana throughout the next century. A multitude of cookery texts—written by whites and African Americans, home cooks and professional chefs, community organizations and businesses—provided recipes that filled pots and pans both regionally and nationally. In 1971, Time-Life’s Foods of the World series identified Louisiana as the only state worthy of its own cookbook, elevating Creole and Cajun fare to the height of other international cuisines. In the following decades, Cajun cookbooks, exemplified by Paul Prudhomme’s Louisiana Kitchen, and foodways reached unprecedented levels of popularity.

Early Creole Cookbooks

Following a trend apparent throughout the United States, the first New Orleans-published cookbook was a reprint of an earlier European work. Reprinted in 1840, La Petite Cuisinière Habile was America’s first French-language cookbook. Louisianans would have to wait until the end of the Civil War to see their cuisine represented in cookbook form. In 1866, Ellen J. Verstille published Verstille’s Southern Cookery. Born in Georgia, Verstille seems to have spent little time in the state, though she was listed on the cookbook’s title page as “of Louisiana.” Whatever her origins, Southern Cookery includes five gumbos, three turtle soups, six bread puddings, and a dozen oyster dishes among its hundreds of recipes. Abby Fisher, a professional chef and South Carolinian living in San Francisco, became the first African American to publish a cookbook in 1881. What Mrs. Fisher Knows about Old Southern Cooking shows that dishes associated with Louisiana, such as “Ochra Gumbo” and “Jumberlie—a Creole Dish” (jambalaya) had disseminated throughout the nation.

In 1884–1885, New Orleans’ tourism and cooking industries received a boost when the city hosted the World’s Fair, or as it was officially called, The World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition. Two cookbooks sought to capitalize on the city’s role in a resurgent South. Lafcadio Hearn’s La Cuisine Creole—published anonymously by the Greek-born writer—documented the foodways of “cosmopolitan” New Orleans and argued that the city’s cookery should be elevated to the status of cuisine, the food of a community. The Creole Cookery Book (1885), compiled by the affluent members of the Christian Woman’s Exchange, helped raise money for the society’s new headquarters and argued for the elevation of the city’s cooking to its “proper place in the gastronomical world.” Commonly referred to as the first Creole cookbooks, these two recipe collections are similar, both opening with a section on soup followed by hundreds of recipes in many diverse chapters. Though both were important in establishing and promoting the city’s cuisine, very few of the recipes would be recognized as representative of New Orleans today. Many were instead pilfered from popular American and Anglo collections of that time.

Popular Creole Cookbooks

The twentieth century heralded the popularization and systematization of New Orleans’s Creole cooking style. Having regularly published a cooking column, New Orleans’s most circulated newspaper entered the recipe business with The Picayune’s Creole Cook Book in 1900. Highly descriptive and exhaustive, the Picayune collection opened with a detailed history of Creole coffee and concluded with meticulous lists of household hints and daily, holiday, and banquet menus. The Picayune’s scope, readability, and practicality remain indisputable; the cookbook contains separate chapters for traditional gumbos, Louisiana rice, Creole candies, and Creole breads. With fifteen editions published, the cookbook’s immense popularity persists today. The Picayune’s Creole Cook Book also firmly established a mythology about New Orleans cooking. The book’s introduction described Creole cookery as combining “the best elements of French and Spanish cuisines,” and suggested that “white mistresses” generally gave their “Negro cooks” recipes to follow. The book’s purpose, its authors claimed, was to gather recipes “fast disappearing from our kitchens” and in danger of becoming “a lost art.” The Picayune’s Creole Cook Book literally whitewashed history by diminishing the contributions of African, Caribbean, and Native American (among others) to Creole culture.

Countless other cookbooks followed The Picayune’s Creole Cook Book’s lead by presenting erroneous and bigoted interpretations of New Orleans’s culinary history. Often these cookbooks, such as Célestine Eustis’s Cooking in Old Creole Days (1903) and Natalie Scott’s 200 Years of New Orleans Cooking (1931), offered romantic remembrances of antebellum days and included Jim Crow-era stereotypes, like the Mammy caricature. In 1978, Nathanial Burton and Rudy Lombard launched Creole Feast, edited by Toni Morrison, in an effort to reverse the “curious effort to ascribe a secondary, lowly or nonexistent role to the black hand in the pot.” Burton and Lombard’s cookbook highlighted fifteen African American “master chefs” and revealed the “secrets” that had been ascribed only to white cooks. Creole Feast alumni soon issued their own cookbooks. Austin Leslie’s Chez Helene: House of Good Food Cookbook came out in 1984, followed by Leah Chase’s The Dooky Chase Cookbook in 1990.

Cajun Cookbooks

Peter Feibleman’s 1982 study American Cooking: Creole and Acadian compared “two aspects of a great cuisine”: Creole, prepared by servants in the stately residences of New Orleans’s elite, and Cajun, assembled in a black iron pot near the bayou. Though undeniably adhering to local stereotypes, the Time-Life cookbook—compiled with the native expertise of Marcelle Bienvenu—is now an out-of-print classic, featuring full-color photographs and lengthy descriptions of Louisiana’s culinary culture. As in early Creole collections, the earliest Cajun cookbooks were issued by a newspaper, the Daily Iberian’s Creole Cajun Cookery (1952), and a social organization, First, You Make a Roux (1954), by Lafayette’s Les Vingt Quatre Club.

In the 1980s, the debut and rise of Cajun chef Paul Prudhomme radically transformed the way Louisianans and the world cooked and ate. The cover of Chef Paul Prudhomme’s Louisiana Kitchen (1984) showed the famously Falstaffian gourmand smiling and surrounded by an abundance of Cajun delicacies: andouille sausage, gumbo, seafood jambalaya, a moon-sized sweet-potato pecan pie, and a massive prime rib prepared Cajun style. The Opelousas-born, New Orleans-based Prudhomme celebrated Cajun specialties old and modern; his illustrated chart of various rouxs has become one of the most referenced cookbook pages in the history of Louisiana cooking.

Contemporary Cookbooks

Since the publication of the city’s first recipe compilations, New Orleans restaurants have capitalized on their renown by issuing cookbooks, beginning with Mme Begué and Her Recipes: Old Creole Cookery in 1900, continuing to Antoine’s Restaurant Since 1840 Cookbook (1979), and the recent Real Cajun by Donald Link (2009). The Encyclopedia of Cajun & Creole Cuisine, chef John Folse’s definitive 2004 work, provides both a quality history of the fare and an excellent recipe compendium. The fields, woods, and waters of north Louisiana rarely receive attention, in cookbooks or otherwise; however, Red River Valley native Mary Land wrote the first comprehensive statewide cookbook, Louisiana Cookery (1954). Meanwhile, community cookbooks remain the go-to guide for many Louisiana households. Two of the most noteworthy examples, and the sequels they spawned, come from area Junior Leagues: Baton Rouge’s River Road Recipes (1959) and Lafayette’s Talk About Good! (1967).

With the destruction of thousands of residences following Hurricane Katrina, cookbooks naturally became sought-after items in the struggle to rebuild. Two cookbooks compassionately aimed to replace the multitude of recipe and cookbook collections lost in the floodwaters. Elsa Hahne’s You Are Where You Eat (2008) collected recipes and oral histories from home cooks in thirty-three distinct New Orleans neighborhoods. In Cooking Up a Storm (2008), Marcelle Bienvenu and Judy Walker hunted down hundreds of recipes requested by New Orleans residents who feared their favorite recipes had forever been washed away.