Anglo-Americans

While Louisiana began as a French colony and its dominant culture remained Creole French well into the nineteenth century, Anglo-Americans began to form a significant minority in region the late colonial period.

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection.

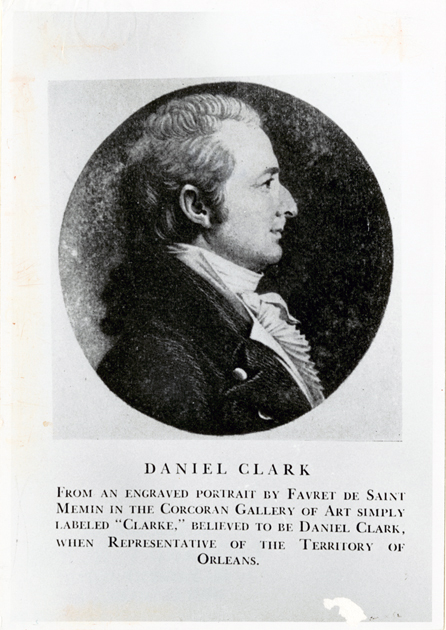

Daniel Clark, the first Delegate from the Territory of Orleans to the United States House of Representatives was born in Sligo, Ireland and arrived in New Orleans in 1786.

While Louisiana began as a French colony and its dominant culture remained Creole French well into the nineteenth century, Anglo-Americans began to form a significant minority in the region in the late colonial period. After 1803, when the Louisiana Purchase added the colony to the United States, Anglo-Americans began arriving in rapidly increasing numbers, lured by ambition, cheap land, and government posts in the new territorial regime. The ensuing tensions between Creoles and Anglo-Americans, though sometimes exaggerated, played an important part in the social development of early Louisiana.

The term “Anglo-American” was used primarily in the late colonial and early national periods (1790–1830) by French-speaking Louisianans to describe English-speaking newcomers—especially those from the United States. English speakers from England, Scotland, and Ireland might also be classified as Anglo-Americans, especially if they became US citizens and sided, as most did, with the American faction in New Orleans. Those newcomers born in the United States were commonly called “Native Americans” (not to be confused with indigenous Indians).

In practice those described as Anglo-Americans tended to be of elite status. The term was not usually applied to the working-class sailors and boatmen who migrated to New Orleans (and who were more often labeled “Kaintocks”). While it might be applied to settlers in upcountry parishes like Ouachita and Concordia, it was most often used to describe the professional and mercantile arrivistes of territorial New Orleans—men who came to make fortunes in Louisiana as merchants, land speculators, and lawyers.

The Colonial Period: Merchants and Speculators

Before 1783 there was little immigration from the British North American colonies to Louisiana. If such colonists wanted to relocate southward, they could choose the British colony of West Florida, which included thriving planter communities around Natchez and Manchac. After the American Revolution (1775–1783), the wave of Loyalist émigrés leaving the former colonies went mainly to Canada, the Floridas, and the British Caribbean. Later in the 1780s, however, governor Esteban Miró tried to attract western American settlers with promises of free land and religious toleration. Land-hungry migrants (including, at one point, Daniel Boone) took Spanish loyalty oaths in exchange for generous grants, but ultimately most American settlers of the 1780s preferred to move to West Florida (now retroceded to Spain) or to settlements in northern parts of the Louisiana territory beyond the borders of the future state.

In the 1790s, closer commercial links with the United States and liberalized Spanish policies toward American merchants started to attract ambitious Anglo-Americans to southern Louisiana, and New Orleans in particular. Credit connections with northern cities multiplied, and American shipping dominated both imports and exports in what emerged as a major commercial port and thriving international city. Many of the new arrivals were Atlantic world cosmopolitans with malleable national identities. Irish-born Daniel Clark, Jr., who served as the first representative of the Territory of Orleans in the US House of Representatives, provided an interesting example. After working as a young man in Philadelphia, Clark moved to New Orleans about 1790, learned Spanish, and became a trusted protégé of Governor Francisco Luis Hector baron de Carondelet. But then, after a quarrel with Spanish authorities in 1798, he took the oath of US citizenship in nearby Mississippi Territory and began agitating for an American takeover of Louisiana. Clark would become one of Louisiana’s wealthiest merchants, planters, and landowners.

The reputation of New Orleans for unhealthiness dissuaded many wealthy merchants from relocating there. Instead they sent young surrogates—such as John McDonogh, who found wealth and fame in colonial New Orleans. Sent at age twenty to represent the commercial interests of William Taylor of Baltimore, McDonogh soon began trading on his own account. He also branched out into sugar planting, slave importation, and land speculation. McDonogh’s land investments in West Florida and his plantation on New Orleans’s West Bank eventually made him one of the richest men in antebellum Louisiana. Later he became famous for the compensated emancipation and colonization program he offered his slaves, as well as for posthumously endowing the public school systems of both Baltimore and New Orleans—where numerous McDonogh schools still exist.

McDonogh and Clark were not alone in their interest in West Florida lands. In fact, soon after his arrival, incoming American governor William C. C. Claiborne noted with dismay that almost all Americans in New Orleans were deeply involved in the speculations. Another large-scale speculator, Dr. John Watkins of Virginia, had studied medicine in Philadelphia, practiced in Lexington, Kentucky, and then tried his hand as an Indian trader in the Illinois territory, before moving to New Orleans in 1799. On his arrival, he petitioned Governor Manuel Luis Gayoso de Lemos y Amorin to grant him a massive tract in North Louisiana to be settled by his “Kentucky Spanish Association.” This came to nothing, but Watkins did succeed in marrying into a prominent Creole family and later becoming mayor of New Orleans.

The Territorial Period and the Generation of 1804

With the news of the Louisiana Purchase in the summer of 1803, an ambitious cohort of Americans began to arrive in New Orleans. Mostly young men of the postrevolutionary generation, frustrated by the lack of opportunity in the Atlantic states, they sought jobs in the new territorial regimes and fortunes in sugar planting, speculation, and lawyering. Many also earnestly looked forward to participating in the republican transformation of the longtime Spanish colony and saw themselves as agents of American sovereignty. Others came fleeing personal, financial, or legal troubles and hoping to make a fresh start. One of the best-known men of the era, lawyer-politician Edward Livingston, came to escape both personal debts and an embarrassing scandal that led to his ouster as mayor of New York City. Livingston had been a three-term representative in the US Congress, and his eldest brother, Robert, negotiated the Louisiana Purchase. So, in spite of his checkered past, he assumed a prominent role in New Orleans affairs from his arrival.

Livingston was in some ways perfect for Louisiana: an eloquent speaker of French, expert in civil law, and close friend of the most famous Frenchman in early America, the Marquis de Lafayette. Livingston soon proved a divisive figure, however, becoming the center of a discontented opposition to the regime of Governor Claiborne. Like many Americans in Louisiana, Livingston was also tainted by allegations that he participated in the Burr conspiracy (a failed attempt, allegedly led by former Vice President Aaron Burr, to create an independent country in the southwestern United States). Livingston eventually earned the bitter enmity of both the US government and the elite Creole class with his efforts to claim the New Orleans batture as his own property. In 1815 he redeemed himself by playing a major role in the Battle of New Orleans. Later he joined Louis Moreau-Lislet and Pierre Derbigny in writing the new Louisiana legal code of the 1820s (though Livingston’s famous penal code was never adopted).

According to New Orleans lore, Creoles viewed American newcomers with aristocratic disdain—to the extent of shutting them out of the main part of the city and forcing them to settle in the American sector, known as Faubourg St. Mary, on the upriver side of Canal Street. In reality, as historian Joseph Tregle has shown, the long-prevailing view of Canal Street as an ethnic dividing line was highly exaggerated. Especially before 1830, Americans lived throughout the city. Nor were they generally shunned: They entered business partnerships and political alliances with Creoles, emulated Creole manners, and many, like Livingston, Watkins, and Claiborne, married into Creole families. A rivalry between Creoles and Anglo-Americans certainly existed—but it was complicated by cross-ethnic alliances and counterbalanced by the racial solidarity that bound all whites in a majority black city.

The Antebellum Period: Divided City, Anglo Upcountry

Nonetheless, antebellum politicians eventually became adept at playing up intra-white tensions and national differences for electoral purposes. Even in the move to statehood in 1812, the incorporation of the mostly Anglo Florida Parishes into Louisiana was calculated to give a strong boost to American influence in state politics. By 1836 the rivalry in New Orleans had grown so bitter that the city officially split into three separate municipalities: the First (consisting of the French Quarter and Treme), the Second (the Central Business District and Lower Garden District) and the Third (the remaining neighborhoods below Esplanade Avenue). Anglo-Americans still remained a minority, making up perhaps 15 percent of the city’s free population. By allying with the massive German and Irish immigrant communities arriving after 1830, however, they were able to assume political dominance. As a result, when the city was “reunited” in 1852, it was under primarily American leadership. (Around that time, the city also absorbed the mostly American suburb of Lafayette, incorporating it into the area now known as Uptown.)

By this time, Americans dominated the legal and medical professions in New Orleans, as well as its commerce. They also, unsurprisingly, founded the city’s Protestant churches. Some Americans brought a Yankee prejudice against Catholicism and “Latin” cultural ways, while others engaged with New Orleans’s dynamic society and influenced its traditions. In 1857, for example, a group of Anglo-American merchants formed the Krewe of Comus. With elaborate costumes, themed floats, and published parade routes, Comus led the transformation of chaotic Carnival celebrations into the modern form of Mardi Gras—a form both less threatening and more centered on the city’s well-to-do Anglo-Protestant population.

Meanwhile, the northern and central rural regions of Louisiana saw massive Anglo-American settler immigration—especially after Henry Shreve cleared the Red River Raft in the late 1830s, allowing for its navigation. Newly formed parishes such as Winn, Claiborne, and Caldwell had English-speaking populations from their inception: cotton planters along the major rivers and poorer subsistence farmers in the upcountry districts. It was the latter whose political pressure led to the Jacksonian Constitution of 1844—which called for white male suffrage for the first time in Louisiana and mandated the removal of the state’s capital from Creole-dominated New Orleans. With the rise of the domestic slave trade from Virginia and Maryland, even the state’s slave population became more English-speaking and less Catholic. Outside of New Orleans, the lower Mississippi, and the Acadian parishes to the southeast and southwest, the term Anglo-American ceased to have much application in Louisiana by about 1860—it simply described the majority population and culture.

The Union occupation of New Orleans from 1862 to 1865 and the subsequent Reconstruction government comprised another Anglo-American “invasion” in southern Louisiana even larger than that of 1804—and, for the Creole elite (who were closely associated with the Confederate cause) a much more threatening one. The Constitution of 1868 excluded the French language from elementary schools and dictated that official laws and court proceedings would be written in English. As the elite francophone population became an embattled minority, they retreated into a defensive mythos of lost aristocratic Creole culture. Ironically, this mythos was constructed, in large part, by Anglo-American writers such as Lafcadio Hearn and George Washington Cable.

The Perspective of the Present

With the closer integration of Louisiana into the American union, the distinction between whites born in Louisiana and those born in the Atlantic states gradually diminished. In New Orleans, the arrival of successive waves of white immigrants—particularly Germans, Irish, and Italians—made the binary distinction between the French and Americans seem outdated. And, as in the rest of the South, the dominant, overpowering social distinction from Reconstruction onward was not ethnic or cultural but racial, as increasing segregation between blacks and all whites obscured divisions within these groups.

In the twentieth century, ethnicity was usually associated with minority status. Louisiana’s diverse array of colonial-derived ethnic groups began to see their varied identities as sources of cultural pride and clan solidarity. In contrast, the Anglo-American majority became a background against which other groups defined themselves. Most Anglos would have denied that they had an ethnicity at all—preferring the assimilative vision famously expressed by French-American writer J. Hector St. John Crèvecoeur in his 1782 Letters From An American Farmer: “Here individuals of all races are melted into a new race of man, whose labors and posterity will one day cause great changes in the world. Americans are the western pilgrims.”

Historians no longer see Louisiana history as a binary struggle in which an Anglo-American minority was able to superimpose its culture and Americanize an unwilling Latin colonial population. Instead, they tend to argue that Anglo cultural forces interpenetrated French and African ones to create syncretic cultural expressions that were unique to Louisiana. Mardi Gras, for example, draws on English Shrove Tuesday and Twelfth Night celebrations, as well as the Catholic carnival tradition. Conversely, many influential Louisianans of French ancestry, such as naturalist John James Audubon and jurist François-Xavier Martin, spent decades in the United States before migrating to Louisiana. Moreover, all European-descended Louisianans were subject to the influence and proximity of African culture, which persisted in the state’s black population. Nor, finally, could the Americans function as a unified, monolithic cultural group, in an era when the term encompassed such diverse people as British merchants, Yankee lawyers, Southern planters, and itinerant Kentucky boatmen—all of whom, along with numerous others, could be given the Anglo label.