French Quarter Renaissance

In the 1920s, a bohemian scene emerged in the French Quarter of New Orleans that contributed to its preservation and revitalization as a tourist destination.

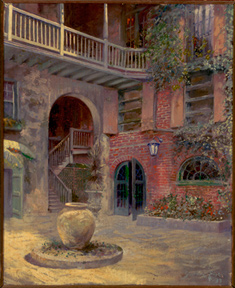

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

Brulatour Courtyard. Goodman, Earl (Artist)

In the 1920s, a bohemian scene emerged in the French Quarter of New Orleans that The Double Dealer magazine hailed as “the Renaissance of the Vieux Carré.” Some of the writers, artists, poseurs, and hangers-on involved were consciously trying to replicate the better-known bohemian enclaves of Paris and New York City, and in many respects they succeeded. With the support of local patrons, this creative community formed a number of cultural institutions—some short-lived but others more enduring—and contributed to the historic preservation and commercial revitalization that turned the French Quarter from a slum into a tourist destination and a fashionable residential center. Ironically, over time this transformation eventually drove out many of the working artists and writers who had helped to bring about the neighborhood’s revitalization.

Origins

Anthropologist and novelist Oliver La Farge described the French Quarter of the 1920s as “a decaying monument and a slum as rich as jambalaya or gumbo.” Most of its once-elegant buildings had been divided into tenements rented to the poor, notably to the first- and second-generation Sicilian immigrants who, according to one estimate, made up eighty percent of the resident population in 1910. In the years during and just after World War I (1914–1918), artists and writers began to move into the area immediately around Jackson Square. They were attracted by the cheap rents, faded charm, and colorful street life.

Although a few of the Quarter’s new residents were native New Orleanians, most came from elsewhere. Several of them wrote for the city’s daily newspapers and encouraged the developing scene by reporting on it. Lyle Saxon, for example, one of the first to adapt an historic building in the Quarter for his own use, used his platform at the Times-Picayune to encourage artists and writers to do likewise. Natalie Scott, a society columnist for the States, chronicled and promoted the bohemian goings-on in the Quarter, bought and restored several buildings, rented apartments to artists and writers, and lived in one herself.

Another source of aspiring bohemians was Tulane University. Its architecture students had for some time been making measured drawings of the French Quarter’s old buildings, and art students from Sophie Newcomb College, the university’s college for women, had been painting and drawing the picturesque ones. Graduates and faculty members from both programs established studios in the Quarter, showed their work in its galleries, and lived and socialized there. Other Tulanians did so as well, such as Frans Blom and La Farge of the university’s Middle American Research Institute, who helped to establish a continuing Mexican connection that brought Mexican artists and writers to town and sent New Orleanians south for summer visits—and, in a few cases, permanently.

Business interests have often been cast as the villains in the story of the Quarter’s revival, and it is true that some shortsighted developers were eager to raze the neglected historic district and replace it with clean and modern buildings. But it should be noted that many businesspeople saw the unique neighborhood’s commercial potential. In fact, the first practical proposal for large-scale renovation came from the president of the Association of Commerce, who suggested in 1919 that the Pontalba buildings flanking Jackson Square should be converted to studios and living spaces for artists. Looking back, photographer William “Cicero” Odiorne observed that “the revival of the old Quarter was a sort of civic project.” Uptown New Orleanians were interested in “French Quarter Bohemianism,” he said, because people like him were “useful.”

Personalities and Social Life

One of the Quarter’s best-known figures at this time was William Spratling, a young artist on the architecture faculty at Tulane. In 1926 he and his roommate William Faulkner (not yet a famous writer) self-published a slim book, Sherwood Anderson and Other Famous Creoles, which Spratling described later as “a sort of mirror of our scene in New Orleans.” Composed simply of Spratling’s drawings of their friends and an introduction by Faulkner, the book gives an idea of the sort of creative figures involved in the Renaissance. It included painter and teacher Ellsworth Woodward, lithographer Caroline Wogan Durieux, photographer “Pops” Whitesell, architects N. C. Curtis and Moise Goldstein, and Mardi Gras designer Louis Andrews Fischer, as well as pianist and composer Genevieve Pitot, activist and preservationist Elizebeth Werlein, and Tulane cheerleader Marian Draper. The best known of the “Famous Creoles” today, however, are undoubtedly some of the dozen or so writers, including the young Faulkner, the even younger Hamilton Basso, and, of course, Sherwood Anderson.

Already a celebrated writer, Anderson first visited New Orleans in 1922, found it “surely the most civilized spot in America,” and returned to take up residence in 1924 with his new (third) wife, Elizabeth. Anderson quickly became, in Spratling’s judgment, “the Grand Old Man of the literati in New Orleans.” The Andersons were at the center of the Quarter’s busy social life in the mid-1920s, their apartment in the Upper Pontalba building the scene of almost nightly gatherings and their Saturday dinner parties as occasions for introducing locals to such visitors as writers Carl Carmer, Anita Loos, Edmund Wilson, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and John Dos Passos as well as publishers B. W. Huebsch and Horace Liveright.

Contemporary accounts and memoirs make it clear that most of the Quarter’s new residents enjoyed what Elizabeth Anderson recalled as “a social and congenial time.” Even impecunious young bohemians (all of them white, in Jim Crow Louisiana) could usually afford African American “help,” who made the frequent dinner parties and other entertaining possible. Faulkner, Spratling, and La Farge, for example, shared the services of a cook, who washed and cleaned as well.

The Quarter also offered cafés for midday coffee and conversation, inexpensive Creole and Italian restaurants, and an abundance of Prohibition-era speakeasies (at one point, Elizebeth Werlein counted seventy-four in a nine-block radius). The ordinary social round was punctuated by special events, such as the racy, more or less annual “Bal des Artistes” to benefit the Arts and Crafts Club, or an ill-starred cruise on Lake Pontchartrain that Sherwood Anderson organized (immortalized, after a fashion, in Faulkner’s novel Mosquitoes), all of it fueled by a flood of illegal alcohol. Elizabeth Anderson recalled, “We all seemed to feel that Prohibition was a personal affront and that we had a moral duty to undermine it.”

New Institutions

Several new institutions contributed to this flourishing of cultural activity and benefited from it. All were largely bankrolled by businesspeople and philanthropists who were not themselves bohemian but who valued the presence and enjoyed the company of those who were.

The Double Dealer was a literary magazine founded in 1921 by two men from prominent New Orleans Jewish families. For its five years of existence, it provided a gathering place and rallying point for the literary component of the Renaissance. The Arts and Crafts Club was for artists what The Double Dealer was for writers. Its lectures, classes, exhibits, and salesroom were open to the public, and its activities received extensive coverage in the local newspapers. The club was largely funded by Sarah Henderson, a sugar-refinery heiress, and its activities appealed to a mix of working artists, serious amateurs, and the merely “artsy.”

Le Petit Théâtre du Vieux Carré—which began as the Drawing Room Players in Uptown New Orleans but moved in 1919 to the Quarter, where it remains today—also provided a place where high society could mingle with Bohemia. Many of the Quarter’s artists, writers, and musicians were involved in production and design; the theater’s founders, its management, and most of its audience were drawn from more privileged circles; and both groups participated as actors.

Uptown society people were also brought to experience the Quarter’s romance and squalor firsthand when organizations like the Daughters of 1776–1812, the Quartier Club, and Le Petit Salon renovated historic properties to use as clubhouses. Though by no means bohemians themselves, members of these elite women’s groups hosted the more presentable artists and writers as speakers or guests and allied themselves with the Quarter’s artistic element in the nascent historic preservation movement.

Transformation and Decline

Once a critical mass of artists and writers was reached, related businesses began to appear. As early as 1922 a walking tour suggested in The Double Dealer pointed out the Quarter’s “restaurants, auction marts, antique shops and book stalls,” including such bohemian hangouts as John and Grace McClure’s Olde Book Shoppe and the Arts and Crafts Club’s galleries. That same year, a New York Times article titled “Greenwich Village on Royal Street” observed that the Quarter offered “the usual teashops and antique shops and bookshops.” The new cultural and commercial activity meant that Uptown New Orleanians who previously might never have set foot in the Quarter began to venture into it for lunches and shopping, for exhibits and classes at the Arts and Crafts Club, and for plays at “Le Petit.” Visits to the French Market’s round-the-clock coffee stands became a common post-party activity.

Some Uptown visitors liked what they saw so much that they purchased houses as rental property or pieds-à-terre. Some of the more adventurous even moved into the Quarter themselves. Many of them would later be called “fauxhemians,” like the fashionable young couple whose “impromptu studio party” led a society reporter to gush: “That’s one of the advantages of being an artist … , you can give such wonderful parties!” One real artist groused that the Quarter was filling up with the kind of people “who rent an ordinary furnished room and call it ‘my studio.’” In 1922 the New York Times observed, “the French Quarter has suffered the fate of such quarters. It has become a fad. It has become, in a way, fashionable.”

Inevitably, the Quarter’s new appeal was soon reflected in rising rents and real estate prices. In 1925, when Natalie Scott sold a St. Peter Street property she had owned for only sixteen months, she tripled her investment, and the value of Le Petit Salon’s clubhouse almost quadrupled in six years. The days when Lyle Saxon could rent a sixteen-room house on Royal Street for sixteen dollars a month would not come again.

The Quarter was also “discovered” by tourists. In 1924 Saxon published a walking tour of the Quarter in his newspaper column, only to be dismayed by how many people took his advice to come have a look. He wrote later that the place had become a “mad house,” with “a horde of tourists everywhere, and people riding around with horses and buggies, sight-seeing.”

Higher rents meant that fewer working artists and writers could afford to live in the Quarter, and the influx of tourists and of businesses catering to them meant that fewer creative types wanted to live in a neighborhood that was becoming increasingly commercialized. By the 1930s most of those who had been depicted in Sherwood Anderson and Other Famous Creoles had decamped. Faulkner went home to Mississippi, and the Andersons left for the mountains of Virginia. Others went to New York or Paris; some emigrated to Taxco in Mexico and Santa Fe, New Mexico (where they watched the same process repeat itself). Although some vestiges of Bohemia and even a few actual bohemians remained in the Quarter, its bohemian moment had passed.