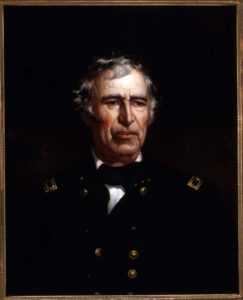

Zachary Taylor

President Zachary Taylor, a shrewd businessman and land speculator, owned a plantation near Baton Rouge that he called home after the 1820s.

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

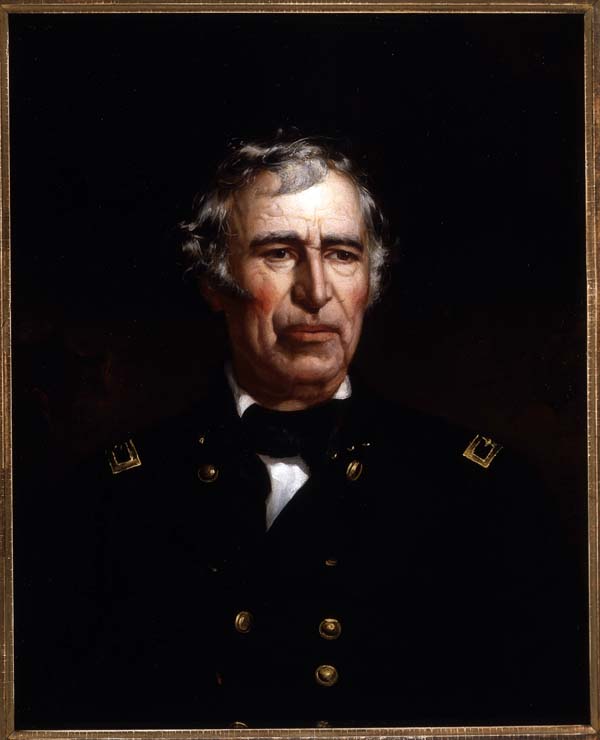

Portrait of Zachary Taylor. Odell, Thomas Jefferson (Artist)

Zachary Taylor, the twelfth president of the United States, served a mere sixteen months spanning the years 1849–50 before his untimely death in office. He was a planter and slaveholder based in Baton Rouge when he entered politics in the late 1840s, a time when northerners and southerners fiercely debated whether Western territories wrested from Mexico should be opened to slavery. Nicknamed “Old Rough and Ready,” before entering politics Taylor had a distinguished forty-year career in the United States Army, serving in the War of 1812, the Black Hawk War, and the Second Seminole War. When some southerners threatened secession, President Taylor stood firm and was prepared to hold the Union together by armed force rather than by compromise.

Taylor was born November 24, 1784, in Orange County, Virginia, to a prominent family of plantation owners. His father, Richard T. Taylor, an officer in the American Revolution, was rewarded for his service with a land grant near Louisville, Kentucky, where Zachary grew up. Although he received little formal education, Zachary Taylor was a shrewd businessman and land speculator who acquired several plantations, including one near Baton Rouge, which he called home after the 1820s. Taylor opposed the spread of slavery (but not slavery as an institution) and dissolution of the Union, but he largely kept his political beliefs to himself. His entry into the presidential race of 1848 struck many observers as a surprise.

His political accomplishments were few, but his military career was impressive and his personal life was full. In 1810, Taylor married Margaret Mackall Smith in Louisville. The couple had six children, including Sarah, who died of malaria shortly after marrying future Confederate President Jefferson Davis in 1835, and Richard, who became a Confederate general during the Civil War.

In 1808, Taylor was commissioned as first lieutenant and began a long military career in the US Army. He was stationed in New Orleans and Terre aux Boeufs, Louisiana, in 1809, but spent much of his service at forts along the frontier. During the War of 1812, Taylor fought Native Americans allied with the British in the Indiana and Illinois Territories, and was promoted to major. In 1820, Lieutenant Colonel Taylor was engaged in the construction of the Jackson Military Road, which connected Columbia, Tennessee, with Madisonville, Louisiana, with a spur from the Pearl River to Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, on the Gulf of Mexico. He found his troops ill fed and poorly supplied upon his arrival but organized the slender resources at his disposal to complete the project. From 1820 through 1821, Taylor was posted in Bay St. Louis and Natchitoches on the Red River, and established Fort Jessup at Shield’s Spring, Louisiana, which commanded the watersheds of the Red and Sabine Rivers.

By 1822, Taylor became commanding officer of Fort Robertson at Baton Rouge, which sat amid the prosperous sugar and cotton plantations of the Lower Mississippi, where he established a plantation even as his itinerant military career continued. He remained at Fort Robertson through the spring of 1824 and returned to Louisiana to command garrisons at New Orleans (1827–28 and 1831). During this time, he speculated in the farmlands of northern Louisiana and purchased a 380-acre plantation in Feliciana Parish, which he often rented and finally sold in 1849 before departing for the White House, along with the Cypress Grove plantation near Rodney, Mississippi. Taylor owned at least three hundred enslaved people in an era when only one percent of slave owners held more than one hundred people. Because Taylor was a largely absentee owner owing to his military service, his plantations were operated by overseers.

Taylor fought in the Black Hawk War (1832) and the Second Seminole War (1837). Promoted to brigadier general, Taylor was responsible for occupying Texas during the republic’s annexation by the United States and by 1846 had established his forces on the banks of the Rio Grande in preparation for the expected Mexican-American War. After the conflict erupted in the spring of 1846, Taylor, although outnumbered by the Mexican army, won victories at Palo Alto, Resaca de la Palma, Monterrey, and Veracruz. His leadership was instrumental in Mexico’s defeat. Lauded by the press as a war hero and savior of the republic, Taylor was promoted to major general and received a congressional commendation. He had become one of the most acclaimed men in America.

Taylor was persuaded to run as the Whig Party candidate for president in 1848 with Millard Fillmore as his running mate. Despite his affiliation, Taylor refused to be bound by the Whig platform. “I am not a party candidate, and if elected cannot be President of a party, but President of the whole people,” he said. Taylor defeated the Democratic candidate Lewis Cass and the Free Soil Party’s Martin Van Buren.

Mounting political turmoil over slavery and western expansion marked his tenure in the White House. Deference to Congress was Taylor’s guiding principal after his inauguration in 1849. Sixty-four years old when he assumed the Presidency, he was already an old man by the measure of his era and the strain of office wore on him. He did not survive his term. Taylor died on July 9, 1850, probably from severe gastroenteritis.