Negro Leagues of Louisiana

The Negro Leagues were the network of African-American baseball teams and players from the 1880s to the integration of baseball in 1946–47.

Courtesy of The Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities

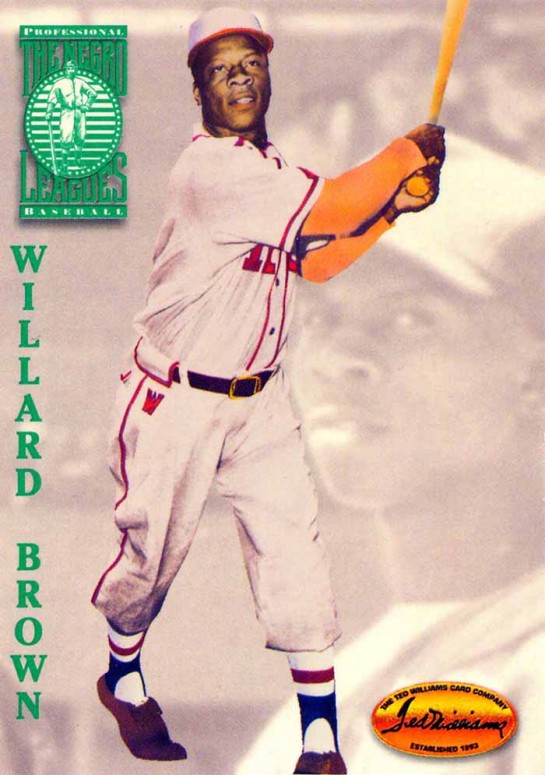

Willard Brown. Ted Williams Card Company (Publisher)

The Negro Leagues were the network of African American baseball teams and players that existed between the informal drawing of the color line in the sport in the 1880s and the integration of “organized baseball” by Jackie Robinson in 1946–47. Officially, the term “Negro Leagues” refers to the organized, structured circuits of teams at various levels across the country that began in 1920, from top-shelf leagues such as the Negro National League and the Negro American League, to smaller-scale operations such as the Negro Southern League and the West Coast Negro Baseball League. But the phrase “Negro Leagues” also loosely includes the amateur, semi-pro, professional, regional, and barnstorming African American baseball teams that existed before, during, and after the formal leagues.

The majority of segregation-era black baseball players and teams in Louisiana fall into this second category. While the Pelican State did play host to several league teams, such as the New Orleans Black Pelicans, the New Orleans Crescent Stars, and the Monroe Monarchs, independent teams were founded in dozens of locales, from larger cities such as Shreveport and Baton Rouge to smaller towns such as Houma, Ferriday, Covington, Slidell, Metairie, and Ruston, down to specific communities and neighborhoods within larger municipalities, such as Meraux and the Melpomene housing project in New Orleans.

Louisiana also served as the home state or longtime residence of numerous African American players of both regional and national renown. Stars who called Louisiana home included Hall of Fame slugger Willard Brown from Shreveport; slick-fielding third baseman Oliver “Ghost” Marcelle from Thibodaux; “Gentleman” Dave Malarcher from tiny Union, who evolved into one of the greatest managers in Negro Leagues history; and Walter Wright, a New Orleans native who, after a successful playing career at the lower professional and semi-pro levels, dedicated his life to keeping the memory of the Negro Leagues, their teams, their players, and their executives alive.

Managers, Owners, and Executives

Louisiana in general, and New Orleans more specifically, were also the bases for several influential managers, owners, and executives who operated and coached pre-integration black Louisiana teams. Leading the way in this regard was Allen Page, a New Orleans-based owner and promoter who used his lucrative hotel business to launch a career that made him the most powerful figure in New Orleans black baseball for decades and placed him squarely in the national Negro League scene as well.

A wide variety of figures owned and operated all-black teams from the late nineteenth century through the gradual demise of the Negro Leagues in the 1950s (a process accelerated by the raiding of African American teams for talent by newly integrated major-league teams). Perhaps the most colorful and famous team owner was New Orleans jazz giant Louis Armstrong, who in the early 1930s owned and outfitted his Secret Nine semi-pro team, which reportedly found its players from the membership of the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club.

Louisiana was also the birthing grounds of talented and popular African American baseball managers, led by Wesley Barrow, who skippered numerous teams across the decades and whose legacy was forever enshrined when the baseball stadium at New Orleans’s Pontchartrain Park neighborhood, a suburban-style development built for African American homeowners in the 1950s, was named after him.

The Emergence of League Teams

The tradition of African American baseball in Louisiana traces its way back to virtually the creation of the sport itself in the mid-nineteenth century, when all-black amateur teams sprouted up in the Crescent City and elsewhere. Initially, because of New Orleans’s more lax adherence to segregation, black and white teams played each other on the diamond, but by the 1880s the firm establishment of the baseball color line eliminated such contests. As a result, dozens of amateur, and possibly semi-pro, aggregations of African American teams congealed and competed against each other in New Orleans, including the Cohens, the Unions, the Dumonts, and the Pinchbacks.

Perhaps the first Louisiana team to gain national prominence was the New Orleans Pinchbacks, an amateur squad named after one of its benefactors, P. B. S. Pinchback, the first African American governor in US history. The Pinchbacks were owned by infamous gambler Walter Cohen, whose aggressive marketing, relentless touring, and uninhibited raiding of other teams for players catapulted him onto the national baseball scene. In 1888 the Pinchbacks declared themselves the “colored national champions” after a successful barnstorming tour through the Midwest. From there, the African American hardball scene in Louisiana blossomed, and by the early 1900s all-black teams of every level could be found across the state.

However, the Pelican State hosted few top-level Negro Leagues teams. New Orleans, despite its large African American population and bustling black economy, was home to arguably only one major Negro League team, and then for just less than two years. In 1940 Allen Page’s persistent and relentless efforts to break the Crescent City into the big time paid off when the St. Louis Stars, a financially beleaguered Negro American League team, decided to divide their home games between St. Louis, Missouri, and New Orleans, thereby being coined the New Orleans-St. Louis Stars. However, the franchise didn’t fare any better in the Crescent City, and the Stars disappeared in the middle of the 1941 campaign.

The only other instance of Louisiana claiming a big-league black team came in 1932, and it occurred largely by happenstance. In the late 1920s white oil baron Fred Stovall, a Texan, created the Monroe Monarchs in that Louisiana city. Located on one of Stovall’s plantations and competing in the sparkling confines of Casino Park, the Monarchs existed as a barnstorming and semi-pro team whose reputation, quality, and attendance slowly grew—the squad became the pride of both black and white Monroe—until 1932, when the franchise formed the cornerstone of the Negro Southern League (NSL).

Thanks to the collapse of the first version of the Negro National League, in 1932 the NSL turned out to be the only African American baseball league operating that year, making it black baseball’s de facto “major league,” which turned the Monroe Monarchs, for one brief, shining moment, into the center of the blackball world. But with the formation of the second Negro National League in 1932, the NSL was demoted to a minor league, and the Monarchs reverted to a sort of “farm team” for the powerful, top-level Kansas City Monarchs. Over the years, several eventual Negro League legends launched their careers in Monroe, including Hall of Famers Willard “Home Run” Brown and pitcher Hilton Smith.

Although the NSL existed as a top-flight organization for only one season, several other Louisiana-based franchises filled the circuit’s roster over the years, including the New Orleans Black Pelicans and, perhaps most significantly, the New Orleans Crescent Stars, who in 1933 grabbed the NSL pennant and squared off against the Chicago American Giants in an informal African American “world series.” The Crescents lost the series to the Giants but earned a niche in Louisiana baseball lore.

Other significant Louisiana Negro Leagues squads included the Shreveport Acme Giants, one of the state’s premier barnstorming teams, especially in the mid-1930s, when the Acmes toured extensively in the Midwest and Canada. The Giants are also known for giving famous player, manager, scout, and Negro Leagues ambassador John “Buck” O’Neil his start in professional baseball.

Other Louisiana metropolitan areas boasted numerous amateur, semi-pro, and touring teams, including New Orleans (Algiers Giants, Black Pelicans), Baton Rouge (Black Sox, Hardwood Sports, West Baton Rouge Cubs), Lake Charles (Lincoln Giants), Alexandria (Aces), and Houma (Delta Cubs).

One quirk of the African American baseball scene in Louisiana is the existence of numerous teams sponsored by and named after local and regional businesses, such as the Jax Red Sox, Dr. Nut Tigers, Flintkote Giants, and Ryan Stevedores.

Another unique—and largely overlooked—aspect of black baseball in Louisiana is another of New Orleans promoter Allen Page’s projects, the North-South All-Star Game. Although not as well known as the famous East-West All-Star Game that developed into the centerpiece of the national Negro Leagues season, the North-South contest also brought together some of the brightest African American hardball talent from across the nation over roughly a decade. Page tirelessly promoted the annual competition, helping enhance his reputation as a top-notch promoter and businessman in the national blackball community.

Hardball Notables

In addition to popular and historically significant teams and events, Louisiana produced dozens of players who went on to varying degrees of success, both on the field and off, in black baseball. Such homegrown hardball notables included the following:

• Shreveport’s Willard Brown, whose prodigious ability to clout home runs earned him a spot, albeit brief, with the major-league St. Louis Browns after the integration of organized baseball.

• Dave Malarcher of Union, who began his career as a player for New Orleans University and went on to successfully manage the legendary Chicago American Giants to multiple titles, and whose intellectual and sportsmanlike approach to the sport earned him the sobriquet “Gentleman” Dave.

• Oliver “Ghost” Marcelle, a Thibodaux native, who many contemporaries considered the best-fielding third baseman in Negro Leagues history and who was almost the polar opposite of Malarcher in terms of demeanor, displaying a quick temper and propensity for alcohol consumption and fighting.

• Johnny Wright, who earned a unique, and perhaps tragic and overlooked, place in baseball history when he was signed to a minor-league contract by the Brooklyn Dodgers shortly after that major-league club inked one with Jackie Robinson. Wright joined Robinson in the minor leagues in 1946, but unlike his eminent counterpart, never made it to the majors, eventually returning to the Negro Leagues before retiring from the game in obscurity.

• Walter Wright, who was born in Natchez, Mississippi, but spent more than eight decades living, playing, and educating in New Orleans. In addition to his on-field accomplishments with Xavier University, the New Orleans Black Pelicans, and other area clubs, Wright (no relation to Johnny Wright) was a steadfast researcher of black baseball history who founded the Old Timers Baseball Club, a group of former Negro League players dedicated to preserving the legacy and memory of African American baseball.

• New Orleans native Edward “Peanuts” Davis, who in the 1940s became one of the most successful pitchers and entertainers in black baseball for such comedic teams as the Indianapolis Clowns and the Ethiopian Clowns.

• Herb “Briefcase” Simpson, a product of New Orleans, whose career blossomed with his hometown Algiers Giants and took him as far as Seattle, Washington, and Hawaii before he returned to the neighborhood that he always called home. As Simpson aged into his nineties, he became one of the last living links to Negro League baseball in Louisiana.

Other Pelican State natives included Red Parnell, Gene Smith, and John Bissant, all of whom reached the upper echelons of African American baseball over the decades.

Overall, in the multiple decades in which segregation and Jim Crow laws existed, several generations of Louisiana’s African American communities savored the American pastime with a passion and nurtured a vast, intricate network of baseball teams and leagues that existed parallel to and in the shadows of “organized baseball,” which for more than a half-century was off limits to black players, managers, and executives who had the same amount of talent and love for the sport as any famous white baseball figures.