Magazine

Clearing the Red

Although it had been there for hundreds of years, Captain Henry Miller Shreve believed he could clear the Great Raft logjam

Published: January 15, 2015

Last Updated: January 30, 2019

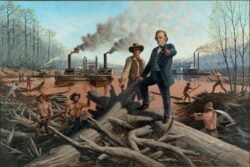

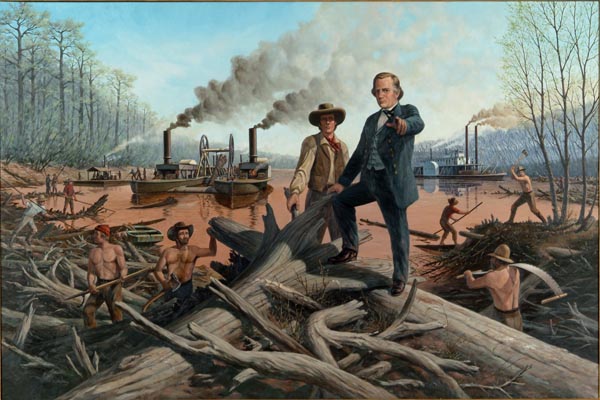

Courtesy of the R.W. Norton Art Gallery.

Hawthorne, Lloyd - painting - "Captain Henry Shreve Clearing The Great Raft From The Red River," 1833-38, Lloyd Hawthorne.

This selection has been excerpted from Historic Shreveport-Bossier, An Illustrated History of Shreveport & Bossier City, published in 2000 for the Pioneer Heritage Center at Louisiana State University in Shreveport by the Historical Publishing Network, a division of Lammert Publications, Inc., of San Antonio, Texas.

The metropolitan area of Shreveport and Bossier City, often referred to as Shreveport-Bossier, began as a commercial venture. The idea of an inland port on the Red River took root in the mind of Captain Henry Miller Shreve of Kentucky, when he brought his flagship Enterprise to Natchitoches toward the end of the War of 1812.Known as the “Superintendent of the Western Waters” for his success in clearing the western rivers of obstructions to navigation, Shreve saw the “Great Raft”—the massive logjams that clogged the Red River north from Natchitoches for more than 400 miles upriver—as a challenge to his ingenuity. The Raft had been there for hundreds of years and was not unknown to Shreve. The French explorer Juchereau St. Denis, who established the fort and settlement at Natchitoches, had explored the bayous and rivers north of Natchitoches and had described the Great Raft that blocked his passage up the Red River.

A hundred years later, Captain Shreve believed he could clear the obstructions and turn the Red River into a navigable inland waterway that would serve a vast area of mid-America. In 1828 Shreve convinced the Jackson administration to award him a contract to clear a navigation channel through the Raft northward from its southern end to Arkansas.

The task facing Captain Shreve was a formidable one. At times the Raft seemed to be a living creature, growing and changing. New mass was added to its upper end as trees and plants caved off the sandy banks. The force and weight of the water’s flow pushed this mass forward and down. This water displacement pushing up on the banks created a system of lakes and parallel channels that complicated the task of making the Red River a navigable stream.

Many of these lakes and channels remain part of the environs of Shreveport and Bossier City today. Caddo Lake, Cross Lake, and Lake Bistineau are three of hundreds of lakes created by the Raft. So great was the water displacement that early government survey maps show Cross Lake and Caddo Lake joined together as a single “open lake.” During the history of the Raft, fingers of the vast open lake system became separate lakes. Ferry Lake, Clear Lake, and Soda Lake were among the finger lakes that joined together when high water occurred to form one huge lake.

Incidentally, “Soda Lake” is a European mispronunciation of the Caddo word “T’Sodo,” meaning “frothy water.” It was never connected with the Spanish explorer DeSoto, as many believe. It seems impossible to believe that 200-foot-long steamboats could traverse the ditch that runs by Querbes Golf Course up through South Highlands and dock at the bluff that is on the south side of Betty Virginia Park. Yet, they did, since Betty Virginia Park was once Deer Lake.

The Raft created much of the geography that is today dry ground in Shreveport and Bossier City. The Cotton Belt Railroad Yard (part of the Southern Pacific and Union Pacific system), located due south of the Civic Theatre and Sports Museum, was once Silver Lake. Fingers from this shallow overflow Raft lake flowed into the low area below the elevated portion of 1-20 where the Ogilvie Hardware building now stands. The office of the Times newspaper is located on Lake Street, so named because during the 19th century the street ran along the shore of Silver Lake. The river’s unpredictable flow patterns, together with commercial development, have destroyed much of this lake topography.

Another low area of Shreveport was created from the swamp caused by overflow from Cross Bayou when its waters backed up behind the dense Raft, which acted as a dam. When the Raft was removed, the water remained, and this boggy, marshy area became known as St. Paul’s Bottoms, taking its name from St. Paul’s Methodist Church. Today, this area is known as Ledbetter Heights, though “heights” is misleading, since the area was never part of the city’s high ground. The name honors the famed musician Huddie (Leadbelly) Ledbetter, who once lived and performed there.

The Challenge

With the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the size of the United States doubled. It was a natural progression in the westward expansion of the United States. However, until Captain Shreve arrived, others had simply accepted that the Raft made navigation of the river impossible.

Though he was awarded the contract in 1828, five years went by while Shreve awaited federal appropriation of funds for the project. At last, on April 11, 1833, with two snagboats, two supply boats, and 160 workmen, Shreve started slicing a narrow shipping channel through the Red River Raft. Crews worked on the shore, aboard the boats, and standing on the logjam itself, using log pikes (peavies), axes, shovels, grappling hooks, and sometimes dynamite, to dislodge the logjams in the bends of the river. The workmen snagged the largest logs and pulled them aboard the twin-hulled snagboats where steam-powered saws cut the logs into smaller pieces that would float downstream on the rising current. Smaller trees, tree roots, and other debris from the logjams were shoved into adjacent bayous to block the outward flow and force the water to stay in the main river channel.

After four months, when operations halted because the funds ran out, Shreve reported that he had cut through 71 miles of Raft to a position between Norris’ settlement and Coates’ Bluff, and that the river current had increased from one-fourth mile to three miles an hour. Shreve requested appropriations of $30,000 annually over the next five years to complete the clearing of the Raft and keep the navigation channel open. He also proposed a new ironclad snagboat, at a cost of approximately $20,000, to replace the wooden snagboats that were constantly in danger from the huge underwater snags.

Shreve’s Ingenuity

Shreve would eventually hold more than 20 patents for devices he created to remove the logjam. Much of the equipment used in the logging industry today has its origins in Henry Shreve’s machinery. He invented the snagboat, which was a catamaran created by bolting two steamboats together and placing on the central common deck a small steam-powered sawmill. He created grappling hook devices, conveyor belt systems, and circular saws mounted for both horizontal and vertical use. Some of the boats were fitted with iron-beaked rams to dislodge logs. Some used long articulating arms with pincers to grab logs and haul them aboard the snagboat for sawing into pieces. Other boats were equipped with horizontal underwater saws which projected out in front of the boats to cut through the log mass below the surface.

Black-and-white reproduction of a photograph of the Red River Raft clearing operations in the 1870s. Courtesy of State Library of Louisiana.

Over the next six years, during periods of high water when his boats could come upriver, Shreve worked to conquer the Red River. Sometimes Shreve’s boats would be delayed for months in getting to the Raft by low water downstream at the Alexandria rapids. There, the boats would have to be unloaded, all cargo portaged upriver and reloaded on the boats once they cleared the rapids. Every time the snagboats returned to the task, there were large sections of new Raft that had formed since the last cut, so the same area had to be cleared again and again. Frequent work delays were occasioned by illness among the workmen as they fell prey to malaria, dysentery, and yellow fever in the humid, mosquito-infested swamps along the river. The second year Shreve requested salary for a doctor to accompany the work crews.

By the end of July 1836, the cost of the project had reached $157,338.62, and river traffic was still impeded by a long stretch of Raft from south of Shreveport to Arkansas. Clearing the dense portions of the Raft was a tedious task. Thirty miles of the upper Raft took longer to clear than the first 100 miles of the Raft below Shreveport. As the Raft closed the river, northbound steamers and keelboats had to go around through adjacent bayous, lakes, and canals, and then re-enter the river above the Raft. Most of the streams in the valley run parallel to the Red River and, indeed, were former river channels. Among these are Bayou Pierre on the Caddo side and Red Chute on the Bossier side -two of the streams that steamboats used to avoid the Raft. In 1873, before the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers made the final clearing of the Raft, both Bayou Pierre and Red Chute were twice the size of the Red River.

Reshaping Boundaries

Shreve’s strategic cuts to shape the navigation channel had far-reaching impact on the history of Shreveport-Bossier. Shreve had authority to remove the Raft in whatever manner he wished. In some places, he would rip through the Raft and let the pieces float downstream on the current. At other locations, he might create a chute or shunt across large meanders, cutting them off from the river and forming oxbow lakes and islands. Examples of these are Wright Island, Anderson Island, Shreve Island, and the island now occupied by Shreveport’s downtown airport.

Shreve’s actions created some interesting situations in the history of Caddo and Bossier parishes. Unfortunately for modern government leaders, Shreve was conducting Raft removal at the very time that Government Land Office crews were surveying and establishing the township range and section grid in Natchitoches Parish, which at that time covered all of northwest Louisiana. Caddo Parish was carved out of Natchitoches on the west side of the Red River. On the east side, Claiborne Parish was separated out of Natchitoches Parish, and later Bossier Parish was created out of Claiborne.

Black-and-white reproduction of a photograph showing the Red River Raft in the 1870s. Courtesy of the State Library of Louisiana.

The river defined the boundary between Caddo and Bossier parishes. When Shreve made a cut that created an island ahead of the government survey crew, the parish boundary at that site was the new riverbed. If Shreve cut the island after it was surveyed, the prior channel was the parish boundary. Hence, the river boundaries were not always the same as the boundaries established by the Government Land Office. This has created havoc, and continues to do so, for governing bodies as the land along the river between Shreveport and Bossier City is developed and redeveloped.

For example, the cut that created Shreve Island set the stage for a legal battle decades later when both Caddo Parish and Bossier Parish claimed this valuable slice of Red River real estate. Some residents of Anderson Island live in the city of Shreveport and the parish of Bossier. Thus, a person buying a house on the Caddo side of the river may discover that he or she is paying Bossier Parish property taxes and Shreveport city taxes. It is also possible that a person could receive a speeding ticket on Clyde Fant Parkway from a Shreveport City policeman and a deputy sheriff of either Caddo or Bossier Parish on the same roadway.

Areas that appear to be in Shreveport but are actually in Bossier are the downtown airport, Wright Island, Barnwell Center, Hollywood Casino, and the log ride at Hamel’s Park. Areas that appear to be in Bossier but are actually in Shreveport or Caddo Parish are most of Cane’s Landing, Casino Magic, and portions of the eastern bank of the river south of Jimmie Davis Bridge.

One important cut was made for economic reasons, to protect the port of the Shreve Town Company from competition. In January 1839, when Captain Shreve’s snagboat, the Eradicator, finally arrived at the Raft after being delayed for months by low water in Alexandria, its first task was to clear 2,300 yards of new Raft that had formed over the past six months. Its second task was unexpected. After clearing through the new Raft, Captain Shreve was greeted with the unwelcome news that a Natchitoches company had laid plans for a competing port at Coates’ Bluff, just three miles downstream. Shreve sent the Eradicator back downriver to cut out a ditch 250 yards wide and three miles long around the point at Coates’ Bluff.

The ditch soon shifted the flow of the river so that Coates’ Bluff was left high and dry without a landing site, so plans to build a town there quickly evaporated.

Finally, on March 20, 1839, the Raft was clear to a point north of Shreveport. The inland port that Shreve had envisioned was chartered that year as Shreveport in his honor. Until the Republic of Texas joined the Union in 1845, Shreveport was the westernmost city in the United States and a gateway to the West. In the 1850s more than 60,000 people passed through the port headed westward. Before the Civil War, Shreveport would become the commercial shipping center for the four-state Red River region of Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas and Oklahoma.

The Raft continued to reconstitute itself with intermittent attempts by others to clear it or cut channels around it. In 1873 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, using snagboats and shallow-draft steamboats designed and patented by Captain Shreve, made the final clearing of the Red River Raft. Steamboat commerce on the Red River would enjoy a second brief heyday before the railroads took over the bulk of transportation.

—–

Marguerite R. Plummer, Ph.D., was the former executive director of the Pioneer Heritage Center and director for the Red River Regional Studies Center at LSU-Shreveport.

Gary D. Joiner, Ph.D., is a cartographer and associate professor of history at LSU-Shreveport. He is past president of the North Louisiana Civil War Round Table and is a scholar of the U.S. Civil War. His weekly radio program on Red River Radio, “History Matters,” is funded in part by the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities.