The Far-Reaching Legacy of Lead Belly

Published: December 1, 2015

Last Updated: August 1, 2016

Music review by Ben Sandmel

Although the eclectic North Louisiana musician known as Lead Belly (Huddie Ledbetter, 1888–1949) is long gone, he still casts a long shadow of influence on popular music. Renditions of songs that he wrote and/or popularized—including “Cottonfields,” “The Midnight Special,” “Goodnight, Irene,” “In The Pines,” and “Boll Weevil”—have scored hits for a variety of artists during the past 65 years, and are still recorded anew today. The stylistic breadth of these songs underscores the fact that while Lead Belly is often designated as a blues musician—implying a limited musical range—he actually personified the far broader “songster” tradition, as previously discussed in this coumn in the Fall 2014 issue.

Huddie Ledbetter grew up in rural Caddo Parish surrounded by a vast wealth of traditional music. The sounds he heard there included blues; African-retentive field hollers and work songs; gospel music and hymns; children’s play songs; archaic British ballads, fiddle tunes, and folk songs, brought to America by 17th and 18th-century immigrants; narrative ballads of more recent vintage, such as “John Henry,” that were common to both the black and white communities in the Ark-La-Tex region; and lilting tresillo rhythms that suggest the possible Afro-Caribbean influence of neighboring South Louisiana. In addition to such folk-rooted material, Ledbetter also encountered and absorbed then-modern sounds—including ragtime and Tin Pan Alley/vaudeville compositions—in nearby Shreveport. He began performing there as a teenager, working in the city’s rough-and-tumble bars. Years later Ledbetter recounted this experience in one of his most evocative original songs, the fatalistic “Fannin Street”:

…My mama told me, my little sister too, women in Shreveport, son, gonna be the death of you.

I told my mama, ‘mama you don’t know, women on Fannin Street kill me why don’t you let me go?’…

Ledbetter further burnished his skills during his mid-twenties by playing in Texas with the great blues guitarist Blind Lemon Jefferson. With such estimable tutelage Ledbetter emerged as a dynamic and versatile musician. Sometimes he sang a capella. More often he accompanied his powerful vocals on twelve-string guitar, or occasionally, on accordion. With his deft, dynamic and relentlessly rhythmic playing—which at times presaged ‘60s funk by three decades—Ledbetter projected more intensity with one acoustic guitar than the cumulative affect of many five-piece amplified bands. With attentive listening to Lead Belly’s guitar work—on songs such as “Fannin Street,” for example—one can easily hear how acoustic-guitar leads morphed into the electronically amplified guitar solos of rock and R&B. As George Harrison of the Beatles once succinctly observed, “No Lead Belly, no Beatles.” Many other rock artists concur.

By his late twenties Ledbetter was incarcerated in Texas, but even behind bars there, followed by another prison-farm sentence in Louisiana, he continued to absorb new material. The comparative isolation of these brutal penal plantations nurtured the survival of antebellum traditions that were fast fading elsewhere—especially songs used to set rhythms for group labor. Prison also provided Ledbetter with the moniker that he used throughout his musical career. It is thought to be a play on his last name combined with an acknowledgment of his toughness and physical strength. (While this name appears in print as both Lead Belly and Leadbelly, the latter spelling is now out of favor, at the request of Ledetter’s heirs.)

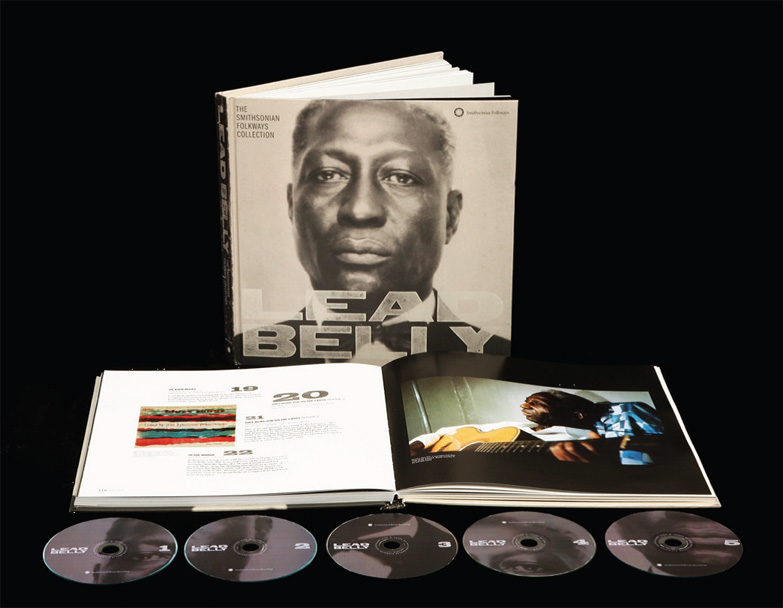

After leaving prison in 1933, Lead Belly further expanded his already rich repertoire to include political and topical commentary (“The Scottsboro Boys,” “The Hitler Song”); adaptations of popular hits (“Springtime In The Rockies,” “Sweet Jenny Lee”) and strong new original material (“Cotton Fields”). A newly released 5-CD/108 song compilation offers an in-depth exploration of his remarkably diverse work, including previously unreleased material. Lead Belly: The Smithsonian Folkways Collection (Smithsonian Folkways) does not present his entire recorded oeuvre, but it does illustrate the entire breadth of his life’s work. It also includes some revealing spoken introductions that illuminate Lead Belly’s personality and explain some of the traditions he represented. One example is “Good Morning, Blues”:

“… And now everybody have the blues. Sometimes, they don’t know what it is. But when you lay down at night, turn from one side of the bed all night to the other and you can’t sleep, what’s the matter? Blues has got you. Or when you get up in the mornin’, sit on the side of the bed, may have a mother or father, sister or brother, boyfriend or girlfriend, husband or wife around. You don’t want no talk out of ’em. They ain’t done you nothin’, you ain’t done them nothin’. What’s the matter, blues got you. Well, you get up and shove your feet down under the table and look down in your place, may have chicken and rice, take my advice, you walk away and shake your head, you say, ‘Lord have mercy. I can’t eat. I can’t sleep.’ What’s the matter? Why, the blues got you. They want to talk to you. You got to tell ’em something.”

The anthology is accompanied by a handsome 140-page book profusely illustrated with rare photos, telegrams, posters, and other such ephemera. The book also features a lengthy, erudite essay by Jeff Place, the archivist for the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, who co-produced this compilation along with Robert Santelli, the executive director of the Grammy Museum. Such elaborate packaging obviously entails significantly increased manufacturing costs and thus a higher retail price. Even so, Place and Santelli decided that this visually rich presentation was essential in today’s digital age. Now that recordings of songs can be purchased individually online, the trade-off for such convenient selectivity is the loss of vital contextual information. “Downloading,” Place told New York Times writer Alan Light, “means missing all of that [Lead Belly’s] story, so we wanted to create a book that has CDs with it, rather than the other way around—a museum exhibit in a coffee-table set.” The resulting compilation does indeed suggest a museum-exhibit quality and, as such, it makes a major cultural statement. (For a full-length biographical study, the book The Life and Legend of Leadbelly by Kip Lornell and Charles M. Wolfe, also comes highly recommended.)

The legendary stature with which Lead Belly is regarded today belies the great frustrations that he experienced during his career. Spending nearly twenty years in jail meant that Lead Belly missed the first great surge of commercial recordings by fellow folk-rooted songsters in the 1920s and early ‘30s. These artists included Blind Lemon Jefferson, and Blind Willie McTell—African-Americans who were both designated as blues artists, for quick reference—and Jimmie Rodgers, and the Carter Family—Anglo-Americans who, with similar over-simplification, were categorized as “hillbilly” singers. Lead Belly, by contrast, made his first recordings in prison, under the aegis of the Library of Congress, when the folklorist John Lomax came to the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola in 1933 on a song-collecting sojourn through the South. The Lomax recordings were never released commercially, since their raison d’etre was documentation. Had they been available, mediocre sound quality and lack of production values might have discouraged sales.

Upon his release from Angola, Lead Belly entered into a complex business relationship with John Lomax, working as both his chauffeur and as a musician whom the folklorist managed—in return for a hefty cut of Lead Belly’s earnings. Lomax garnered lurid and shamelessly racist publicity for Lead Belly’s performances by exploiting his status as a convicted murderer, and tastelessly insisting that he perform at times in prison garb. Not surprisingly, this relationship soon soured, although Lead Belly maintained ties with John Lomax’s son, Alan, an acclaimed folklorist in his own right.

Lead Belly recorded for a subsidiary of Columbia Records in 1935, but these sessions brought no success, possibly because they narrowly focused on his blues material only. In somewhat similar fashion, in 1936, he did not win over the audience at New York’s Apollo Theater, then the ultimate cutting-edge venue for African-American performers. Compared to such popular urbane artists as Cab Calloway, Lead Belly sounded old-fashioned and rustic. A newspaper critic trashed the show. Had he moved back to Caddo Parish, Lead Belly’s rural sound might still have resonated, but, after nearly two decades in Southern prisons, he chose to live in New York.

In ensuing years Alan Lomax made extensive documentary recordings of Lead Belly for the Library of Congress and also set up commercial sessions for him with the folk-revival producer Moses Asch. Prominent presence in this milieu led to Lead Belly’s lionization in the left-leaning music circles typified by such zealous admirers as Pete Seeger and Woodie Guthrie. As a result Lead Belly was scrutinized for possible links with the Communist Party, although his own views were moderate. For the rest of his career Lead Belly performed primarily for white, folk-revival audiences. He continued recording until his death, in 1949, but nothing sold well.

In 1950, however, a rendition of “Goodnight, Irene” became one of the year’s best selling records—for a band called the Weavers, whose members included Pete Seeger. Numerous successful cover versions and adaptations followed, over the years, by the diverse likes of Bob Dylan, British skiffle artist Lonnie Donegan, R&B singer Brook Benton, British rockers Led Zeppelin, California’s Creedence Clearwater Revival, the ‘90s grunge-rock band Nirvana, and singer Johnny Rivers, who launched his career in Baton Rouge. Sadly, many great musicians don’t live to receive their just due. From the perspective of history, however, Lead Belly: The Smithsonian Folkways Collection stands as an appropriately monumental tribute to this iconic Louisianian.

—–

Ben Sandmel is a New Orleans-based freelance writer, folklorist, and producer and is the former drummer for the Hackberry Ramblers. Learn more about his latest book, Ernie K-Doe: The R&B Emperor of New Orleans, by visiting erniekdoebook.com. The K-Doe biography was selected for the Kirkus Reviews list of best nonfiction books for 2012.

(from LCV Spring 2015 Sound Advice)