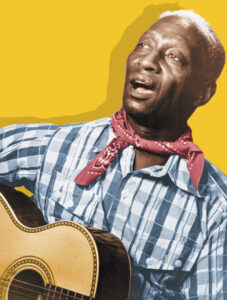

Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter

Huddie "Lead Belly" Ledbetter is one of the most important grassroots musicians of the twentieth century.

LOUISIANA CULTURAL VISTAS MAGAZINE

Huddie "Lead Belly" Ledbetter.

Huddie William Ledbetter stands out as one of the most important grassroots musicians of the twentieth century. He was born on Jeter Plantation in Mooringsport, near the Louisiana-Texas border, around January 20, 1885, to farmers Sally and Wes Ledbetter. As a child, Ledbetter learned to play accordion and basic guitar techniques from his uncle Terrell Ledbetter, and he soon began to perform for parties, known locally as “sukey-jumps.” Ledbetter left home around 1903 and supported himself by working in the cotton fields between Dallas, Texas, and Shreveport during the week and at house parties and country dances on weekends. Ledbetter married his first wife “Lethe” Henderson on July 8, 1908. The couple remained together for about a decade.

Beginning around 1913, Ledbetter spent eight months playing with blues singer Blind Lemon Jefferson, who went on to record some of the most legendary down-home, country blues recordings of the mid- to late 1920s. While playing with Jefferson, Ledbetter heard itinerant Mexican musicians, some of whom played a large twelve-string guitar. The loud, resonant instrument impressed him and he purchased one, never to return to the smaller six-string model of his youth.

Prisons

In 1915 police jailed Ledbetter for assault in Harrison County, Texas, and a judge sentenced him to the chain gang. Within several months, he escaped and relocated to DeKalb County, Texas, living as “Walter Boyd.” For most of the next nineteen years, the state incarcerated Ledbetter for a variety of crimes ranging from simple assault to assault with intent to kill. In 1925, after hearing him perform at the Sugarland Prison near Houston, Texas, Governor Pat Neff granted “Lead Belly” (as he was now known) a full pardon. Ledbetter’s criminal record of rather minor altercations—many almost certainly aggravated by the fact that Ledbetter was Black—furthered his “bad man” image and helped bolster his reputation later, when he moved to New York City.

In the early 1930s, following a racially charged assault incident in Mooringsport, Ledbetter served time in Louisiana’s notorious Angola Penitentiary. His life changed forever in the summer of 1933 when he met John Lomax and his eighteen-year-old son Alan, who were touring southern prisons collecting African American folk songs for the Library of Congress. Angola’s warden recommended Ledbetter, among others, and they held a brief recording session with Lomax. Ledbetter’s music and persona so impressed Lomax that he specifically sought out the musician when he returned the next summer with improved recording equipment. For his second session, Ledbetter reworked his pardon song and addressed it to Louisiana Governor O.K. Allen. At that session, he also recorded the song that would become his trademark, “Goodnight Irene.”

New York City

Following his release in August 1934, Ledbetter sought out Lomax and offered to help him find and document Black folk music in southern prisons. After several months of travel, the pair ended up in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where Lomax presented the singer to English professors at the annual meeting of the Modern Language Association.

Ledbetter proved a sensation upon his arrival in New York City on December 31, 1934. Newspapers printed lurid descriptions of his convict past—the Herald Tribune’s headline, for instance, stated, “Sweet Singer of the Swamplands Here to Do a Few Tunes Between Homicides.” Ledbetter soon sent to Louisiana for Martha Promise, with whom he had taken up after being released from Angola, and married her in Wilton, Connecticut, on January 21, 1935. Cashing in on this publicity, Lomax negotiated a contract with Macmillan Publishers to write Negro Folk Songs as Sung by Leadbelly (1936) and persuaded the March of Time’s newsreel series to film Ledbetter.

Lomax continued to make more recordings of Ledbetter for the Library of Congress, and also arranged a recording contract with the American Record Company (now CBS/Sony). The records sold poorly, underscoring the fact that Ledbetter’s down-home rural style had lost favor in light of the poor economy and the craze for swing music. Progressive white urban intellectuals, however, found him fascinating, and for the rest of his life Huddie Ledbetter entertained audiences that were almost all white.

Ledbetter opened up a new world for New York’s white socially progressive urban folk musicians, such as Burl Ives, Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, and Sis Cunningham. He embodied southern Black musical culture, a “pure” folk aesthetic that was the antithesis of a slick and smooth popular artist like Cab Calloway. For these young folk performers, Ledbetter provided a wellspring of new material like the field holler “Old Hannah;” “The Midnight Special,” a song about a train well-known to Sugarland prisoners; and the blues song “Easy Rider.”

Always ready to innovate and adapt to his environment, Ledbetter added topical and protest songs about segregation (“Bourgeois Blues”), World War II (“Mr. Hitler”), and notable disasters (“The Hindenburg Disaster”) to his repertoire. Although the urban folk movement provided new audiences, the Ledbetters barely survived on musical jobs at union halls and small coffeehouses, as well as welfare. In addition to performing, Ledbetter eventually recorded dozens of selections for Capital, RCA, Musicraft and Asch/Folkways, none of which sold particularly well during his lifetime.

While in Paris late in 1948, persistent muscle problems led to a diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, more commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. Within a year, on December 6, 1949, he succumbed to the disorder. One year later, “Goodnight Irene,” which he had learned from his uncle Bob Ledbetter, became a nationwide number-one hit for the Weavers. Scores of Black and white artists eventually recorded his trademark song.

Legacy

Today, most of Ledbetter’s recordings, including those for the Library of Congress, remain available to the public. He is the subject of a major motion picture, Gordon Park’s Leadbelly (1976), and the award-winning biography The Life and Legend of Leadbelly (1993) by the late Charles Wolfe and Kip Lornell. Artists as diverse as the Beach Boys and Perry Como have recorded Ledbetter’s music. Shortly before his 1994 suicide, Kurt Cobain performed “Where Did You Sleep Last Night?” (a.k.a. “Black Gal”) on MTV’s Unplugged series. Cobain’s young listeners were from a digital world far removed from Ledbetter’s own youth in the South after Reconstruction; nonetheless, the music clearly resonated, as it still does today.