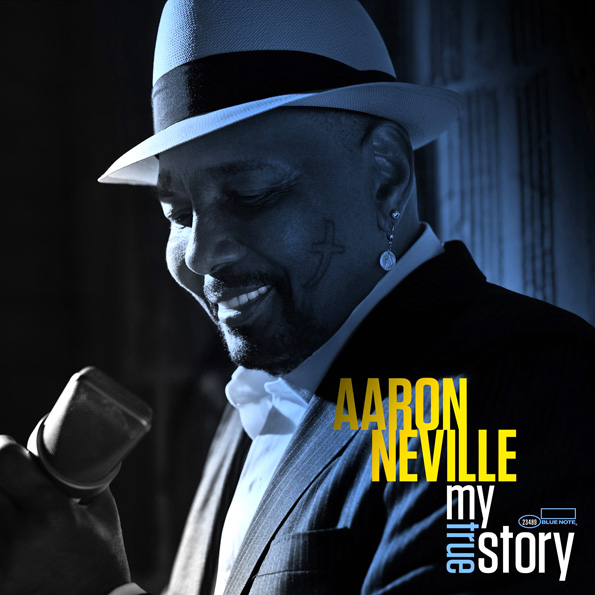

Aaron Neville’s My True Story

Acclaimed singer Aaron Neville records an album of doo-wop classics.

Published: August 30, 2016

Last Updated: December 6, 2018

The acclaimed singer records an album of doo-wop classics

music review by Ben Sandmel

Since the start of his recording career in 1960, Aaron Neville has stood out as one of the most distinctive and affecting singers to ever emerge from New Orleans. Neville’s unique voice and vocal style, simultaneously sensual and ethereal, are immediately identifiable thanks to a suspensefully understated sense of phrasing that paradoxically soars to dramatic, quavering, falsetto flourishes. Neville’s eclectic oeuvre ranges from rhythm and blues to funk, Mardi Gras Indian songs, cover versions of classic country hits, gospel, powerful commercial pop music, and more. He has sung all these genres with consummate professionalism—as a solo artist, in a duet with Linda Ronstadt, and with his three siblings in the Neville Brothers band. He has frequently scaled the pop charts and garnered many major music-industry awards. Despite more than 50 years in the business, though, Aaron Neville has never—until the recent release of My True Story (EMI)—devoted an entire album to his favorite style: doo-wop singing.

Doo-wop is an onomatopoeic term that describes the nonverbal backup vocals used by many popular rhythm & blues groups from the late 1940s through the early 1960s. Like much musical nomenclature—“swamp pop” is another example— “doo-wop” was superimposed on this style retroactively. If asked, during doo-wop’s peak years, most artists who sang it would probably have described their music as R&B. Doo-wop is rooted in African American a cappella gospel quartet singing of the early 20th century, which combined rich group harmonies with alternating lead vocals that used starkly contrasting high and low registers to great effect. Doo-wop also reflects the influence of such popular secular groups as the Ink Spots and the Mills Brothers. Nationally prominent doo-wop groups—many of whom, for some reason, found it trendy to name themselves for species of birds—included the Orioles, the Ravens, the Penguins and the Flamingos. The latter group’s haunting ballad “I Only Have Eyes For You,” from 1959, stands as one of doo-wop’s best-known and most enduring signature songs. So does the up-tempo “Speedo,” by the Cadillacs, from 1955.

Doo-wop is an onomatopoeic term that describes the nonverbal backup vocals used by many popular rhythm & blues groups from the late 1940s through the early 1960s. Like much musical nomenclature—“swamp pop” is another example— “doo-wop” was superimposed on this style retroactively. If asked, during doo-wop’s peak years, most artists who sang it would probably have described their music as R&B. Doo-wop is rooted in African American a cappella gospel quartet singing of the early 20th century, which combined rich group harmonies with alternating lead vocals that used starkly contrasting high and low registers to great effect. Doo-wop also reflects the influence of such popular secular groups as the Ink Spots and the Mills Brothers. Nationally prominent doo-wop groups—many of whom, for some reason, found it trendy to name themselves for species of birds—included the Orioles, the Ravens, the Penguins and the Flamingos. The latter group’s haunting ballad “I Only Have Eyes For You,” from 1959, stands as one of doo-wop’s best-known and most enduring signature songs. So does the up-tempo “Speedo,” by the Cadillacs, from 1955.

Neville was raised amidst the distinctive sounds of New Orleans R&B and Mardi Gras Indian music, which greatly affected him, but doo-wop was always his first love. New Orleans was not a hotbed of doo-wop compared to the Northeast, but the city did nurture such local practitioners as the Spiders, as well as the Blue Diamonds, a group fronted by Ernie K-Doe before he became a solo artist. Although New Orleans is often considered culturally insular and impervious to national trends, the above-mentioned “bird bands” and their colleagues were very popular in the Big Easy, where Neville idolized them. “I went to the school of doo-wop-ology,” he told this writer in a 1990 interview, utilizing a stock phrase that he has imparted to many other journalists before and since. “Doo-wop did something to me,” Neville continued, “and just to be able to sing like that still does something to me. It’s like medicine.” Even so, Neville’s classic ’60s recordings—including “Over You,” “Wrong Number” and his huge hit “Tell It Like It Is”—wisely focused on his plaintive lead vocals, with only minimal backup singing. In those somewhat delicate settings, doo-wop’s polysyllabic and rhythmic intensity might have left Neville somewhat overshadowed.

Back then, Neville was hungry for hits, and he deferred to the sage advice of producers such as Allen Toussaint and George Davis, with successful results. But today, at age 71, established megastardom has given Neville the rare luxury of recording whatever he wants. He has no need to cast an anxious eye towards the music-business marketplace, where doo-wop is currently quite esoteric. Freed from commercial constraints, My True Story showcases Neville in a collection of doo-wop classics made famous by venerable artists including Clyde McPhatter, Hank Ballard, Thurston Harris, Ben E. King, the Drifters, the Ronettes, and the Jive Five, who first recorded this album’s title track.

Neville sings the favored music of his youth with obvious joy and effortless command, choosing well-crafted old songs that are ageless rather than dated. Many such retro albums by major artists on major record labels are glaringly overproduced in an effort to somehow seem modern. Garish, obtrusive orchestration and saccharine string sections often abound. My True Story, by curious contrast, features respected veteran musicians—including The Rolling Stones’ guitarist Keith Richards—who stay out of Neville’s way to the point that their accompaniment sounds anonymous, muted, and lacking in dynamism. Working musicians may well notice this restraint, with no small amount of puzzlement. But it is not apt to mar the listening experience for the general public at all because Neville’s performance here is inspired and fully involved, and his exquisite voice remains absolutely undiminished. Neville’s artistically successful reprise of doo-wop may well bring it back in style.

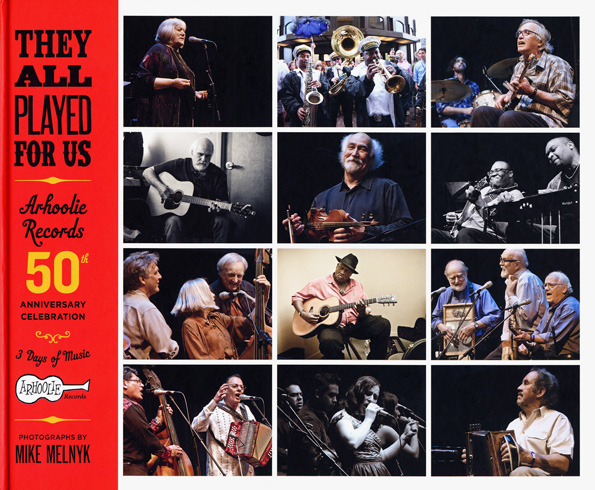

A wealth of other high quality music also demands our attention here. In 1960, the same year that Aaron Neville first recorded, Chris Strachwitz founded the Bay Area-based label Arhoolie Records. This column has often praised Strachwitz’s great contributions to the documentation of Louisiana music in the course of his frequent recording trips here. Strachwitz dissuaded the Hackberry Ramblers from disbanding in 1963, for example, thus encouraging that Cajun/western swing group to keep playing for 42 more years. Strachwitz’s recordings of Clifton Chenier brought zydeco its first exposure to national and then global audiences, and he likewise helped disseminate Cajun music, from traditional artists to such modernists as BeauSoleil.

In 2011, Arhoolie celebrated its 50th anniversary by releasing a four-CD set of its early recordings. Hear Me Howling! came accompanied by a handsome book with the same title. Now Arhoolie has celebrated that milestone again with the release of another four-CD set of live recordings from an anniversary concert held in 2011, entitled They All Played For Us. This collection, too, features a gorgeous companion book. There are rollicking performances by Louisianans David Doucet, the Savoy Family Band, the Savoy-Doucet Band, the Treme Brass Band and the California Cajun group the Creole Belles. Conjunto, bluegrass, jugband music, blues, and steel-guitar gospel are in the mix, too, performed by such leading artists in those fields as Santiago Jimenez, Peter Rowan, Ry Cooder, the Campbell Brothers and Taj Mahal, with exuberant emceeing by Nick Spitzer of public radio’s American Routes.

On a related note, congratulations are due to the second generation of Cajun music’s Savoy family, for sons Wilson and Joel’s involvement—as accordionist and producer, respectively—on the Grammy-winning release The Band Courtbouillon (Valcour). Also featuring accordionists Steve Riley and Wayne Toups, and bassist Eric Frey, The Band Courtbouillon took top honors as the Best Regional Roots album of 2012, disproving the notion that the Grammy Awards are totally dominated by big corporations. Another major Cajun artist—the environmentalist, cultural activist, singer-songwriter and poet Zachary Richard—has just released a powerful, impressive new bilingual album of original material entitled Le Fou (Avalanche Productions/www.zacharyrichard.com).

Outside of Louisiana’s borders, for a moment—but well within its sphere of influence—the delightfully skewed Phil Lee’s The Fall and Further Decline of the Mighty King of Love (Palookaville) combines a seamless blend of southern roots styles with wry, mordant lyrics. The Nashville-based Lee pays obvious instrumental homage to the late Baton Rouge blues master Slim Harpo on the powerful song “Blues In Reverse,” with some strong lines that can’t be quoted in these pages. An equally unflinching stance—one of glum eloquence—characterizes Finds The Present Tense (Rootball/www.gurfmorlix.com) by the acclaimed Austin guitarist, producer and songwriter Gurf Morlix. Morlix has strong Louisiana connections through his work with the evocative songwriter and singer Lucinda Williams. Although Finds The Present Tense is certainly no cheery, perky album, it’s a rewarding listen nonetheless.

Back in Louisiana, the New Orleans traditional jazz scene has been considerably enriched for the past six years by the presence of the excellent young singer Meschiya Lake. While Lake is clearly influenced by the estimable likes of Billie Holiday, Mahalia Jackson, Bessie Smith, and country music’s Hank Williams Sr., she has forged a distinct and highly personal sound. Lake’s voice can be soft and gentle or rough and raw, as the moment demands. She has a masterful sense of phrasing, singing both behind and ahead of the beat, and taking daring rhythmic chances that always resolve right on time. Lake is also a charming, witty performer, as evidenced on the album Live At Chickie Wah Wah (Chickie Wah Wah Records), where she is accompanied by the brilliant and encyclopedic pianist Tom McDermott, whose work will be discussed at length in a future column. (Chickie Wah Wah Records emanates from a New Orleans nightclub with the same name that has emerged as one of the city’s most innovative and eclectic venues. The name “Chickie Wah Wah” comes from the title of an R&B song by Huey “Piano” Smith and the Clowns.)

Back in Louisiana, the New Orleans traditional jazz scene has been considerably enriched for the past six years by the presence of the excellent young singer Meschiya Lake. While Lake is clearly influenced by the estimable likes of Billie Holiday, Mahalia Jackson, Bessie Smith, and country music’s Hank Williams Sr., she has forged a distinct and highly personal sound. Lake’s voice can be soft and gentle or rough and raw, as the moment demands. She has a masterful sense of phrasing, singing both behind and ahead of the beat, and taking daring rhythmic chances that always resolve right on time. Lake is also a charming, witty performer, as evidenced on the album Live At Chickie Wah Wah (Chickie Wah Wah Records), where she is accompanied by the brilliant and encyclopedic pianist Tom McDermott, whose work will be discussed at length in a future column. (Chickie Wah Wah Records emanates from a New Orleans nightclub with the same name that has emerged as one of the city’s most innovative and eclectic venues. The name “Chickie Wah Wah” comes from the title of an R&B song by Huey “Piano” Smith and the Clowns.)

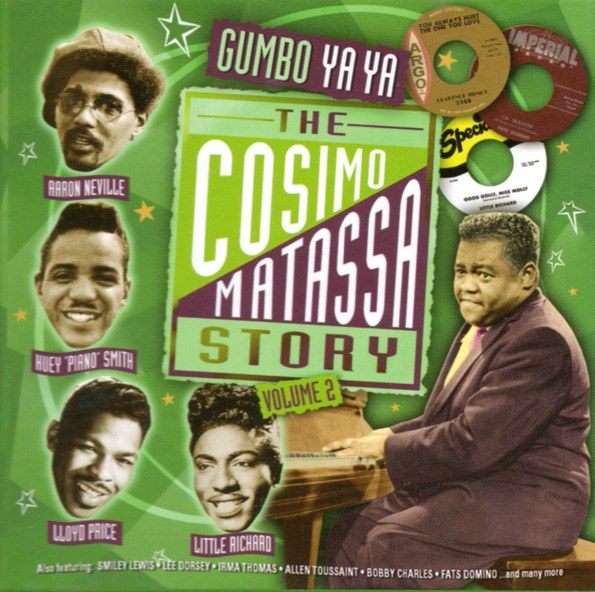

Finally, six years ago the U.K.-based Proper Records released a four-CD set entitled The Cosimo Matassa Story. This set paid apt tribute to New Orleans’ preeminent recording engineer from the 1940s into the ’70s. Without the spirit and technical expertise of Cosimo Matassa, it is safe to surmise that the “Golden Age of New Orleans R&B”—as heard on records by Fats Domino, Aaron Neville, Lloyd Price, and many other local legends—might well have never happened. To a great extent, The Cosimo Matassa Story focused on obscure, lesser-known gems from Matassa’s studio vaults. By contrast, on the recently-released Gumbo Ya-Ya: The Cosimo Matassa Story, Volume 2 (available as an import only), Proper Records has opted for far more familiar material, compiling an impressive, de facto “greatest hits” package of New Orleans R&B that comes highly recommended.

—–

Ben Sandmel is a New Orleans-based freelance writer, folklorist and producer, and the former drummer for the Hackberry Ramblers. Learn more about his latest book Ernie K-Doe: The R&B Emperor of New Orleans by visiting erniekdoebook.com. The K-Doe biography was recently selected for the Kirkus Reviews list of best nonfiction books for 2012.