Magazine

Homage to a Recording Engineer

Published: March 12, 2015

Last Updated: August 30, 2016

The audio artistry of Cosimo Matassa

by Ben Sandmel

In columns such as this where recordings are reviewed, attention typically focuses on the performance by the featured musicians or group at hand, the original compositions and/or other material that they choose, and the work of the producer who conceives and crafts the final product. In these particular pages, the cultural context and specific connections with Louisiana are also considered, and accompanying essays and artwork may be evaluated as well. But the crucial contributions of audio engineers are rarely mentioned here, or elsewhere, even though the sonic quality of a recording — quite apart from the quality of a performance — can be crucial in both its artistic and commercial success. Many seminal and immensely popular records, in many genres, might not have been well received had they not been well recorded. If the listening public does not always recognize a poor recording per se, a lack of sound quality may still determine the public’s tepid response.

This truism is amply evident in the history of New Orleans rhythm & blues, which owes an incalculable debt to the technical expertise and personal integrity of an audio engineer and studio owner named Cosimo Matassa. For three decades, beginning in the mid-1940s, Matassa recorded almost all of the landmark R&B hits by such New Orleans artists as Fats Domino, Lloyd Price, Smiley Lewis, Professor Longhair, Shirley and Lee, Irma Thomas and numerous other icons. When the New Orleans sound of these musicians gained fame as a sure-fire success formula — thanks, in particular, to national hits by Domino and Price — Matassa’s J&M Studio, in the French Quarter, became an audio mecca that was utilized by aspiring pilgrims from around the nation. For instance, this was where, in 1955, Little Richard — from Macon, Georgia — recorded such definitive R&B/rock ‘n’ roll gems as “Tutti Frutti” and “Long Tall Sally,” accompanied by some of New Orleans’ best studio musicians.

Matassa did not produce “Tutti Frutti,” Price’s “Lawdy, Miss Clawdy” or Domino’s “The Fat Man.” A producer chooses songs, arrangements, and instrumentation, hires musicians, and decides which rendition will be used as a final take. Matassa’s job, as engineer, was to ensure that the producer’s aesthetic decisions were captured, on tape, with maximum clarity, presence, and balance. Matassa did just that despite technology of a half-century past that was quite primitive by contemporary standards. Today’s multi-track recording, where each instrument has its own microphone and separate sonic space, did not exist when Matassa started out. Instead, an entire band would record through a handful of microphones, which had to be deftly placed in the room so that no instrument dominated the composite sound, or, conversely, was not loud enough.

The great drummer Earl Palmer — who played on “Tutti Frutti,” and went on to become the premier session drummer in Los Angeles — once told journalist Tony Scherman: “That little room [Matassa’s studio] was hardly bigger than a bedroom. Picturing it, I see Lee Allen and Red Tyler [famed New Orleans saxophonists] in the middle, the piano and me on opposite sides, and the singer by the horns, near the piano. Everyone faced Cos, who was in the little bitty [engineering] booth. Cos never had an assistant; he came in and out and set them mikes himself … I think Cosimo was a genius. I’ve seen engineers use two dozen mikes to get the sound he got with three. He knew how to position mikes and he knew each mike like it was a person. Didn’t even have no mike on the drums, just a mike on the bass and the piano, one on the vocal, and the one that Tyler and Lee used was pointed at the drums. Cosimo knew that room, see. Today they put a dozen mikes on the goddamn drums alone! They put drums in a separate room now, or behind a baffle, but Cos never had no baffles in that room — you couldn’t fit one.”

In addition to his technical expertise — a knack for coaxing a big sound out of little equipment in a small room, if you will — Matassa created a refuge from prejudice and segregation. Behind the closed doors of his studio, black and white musicians could play on each others’ sessions at a time when they could not share the stage in public. Matassa took considerable heat for his egalitarian stance, and pulled no punches in his assessment of the cruel realities involved. As he recently told WWL-TV reporter Eric Paulsen, “Fats Domino sold 20 million records in a row, and the Picayune never heard about it? Now if he’d gotten in a knife fight, he’d have been on the front page…”

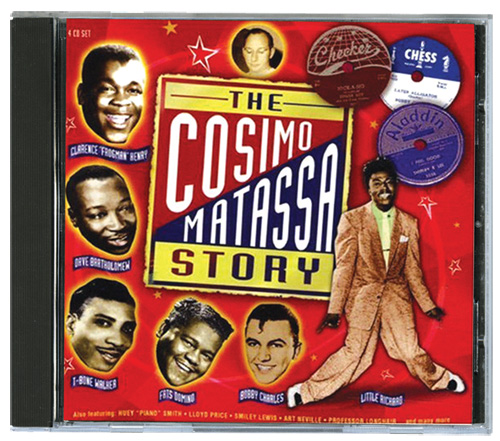

Matassa, a beloved elder statesman of the New Orleans scene at age 81, has received national accolades of late, including a Trustees Award at the 2007 Grammy Awards. And now a 4-CD anthology of diverse material that he engineered — entitled The Cosimo Matassa Story (Proper U.K.; available in America as an import) — has just been released, and it is most highly recommended. Many delights await among the 120 compiled songs that represent a mere fraction of Matassa’s oeuvre. There are well-known hits, including the aforementioned “Tutti Frutti” and “Lawdy Miss Clawdy”; comedic moments such as “Who Drank My Beer While I Was In The Rear” by Dave Bartholomew, the skilled trumpeter and bandleader who produced Fats Domino, and an astounding assortment of animal noises and odd sound effects by the aptly-named Clarence “Frogman” Henry; rollicking instrumentals such as Lee Allen’s “Rocking at Cosimo’s”; esoteric R&B gems including “Just To Hold Your Hand,” by Big Boy Myles, “Travelin’ Mood” by Wee Willie Wayne, and “Rich Woman” by Lil Mallet and His Creoles; a pair of rockabilly tunes by Werly Fairburn, a regular performer on the Louisiana Hayride; hits based on ephemeral street-talk, including “See You Later Alligator” and “Take It Easy, Greasy” by Bobby Charles; strikingly original and articulate songs by Earl King; suave crooning by Art Neville, urgent blues-shouting by Smiley Lewis — and much more.

Matassa has always downplayed his talent and his massive contributions to New Orleans music. “I don’t know if you could call ‘The Cosimo Sound’ that distinctive,” he told journalist John Broven. “I tend to feel less about than other people seem to. I’m not impressed with myself.” This stance is genuine, rather than one of false modesty. With all due respect, however, this writer begs to differ. Earl Palmer was right: Cosimo was a genius.

——-

Ben Sandmel is a New Orleans-based freelance writer, folklorist and producer, and the former drummer for the Hackberry Ramblers. Learn more about his latest book, Ernie K-Doe: The R&B Emperor of New Orleans, by visiting erniekdoebook.com. The K-Doe biography was selected for the Kirkus Reviews list of best nonfiction books for 2012.