Winter 2017

A Carnival Visionary

Louis Andrews Fischer was a Carnival visionary who designed iconic costumes, floats, and sets for Mardi Gras balls

Published: December 8, 2017

Last Updated: February 26, 2019

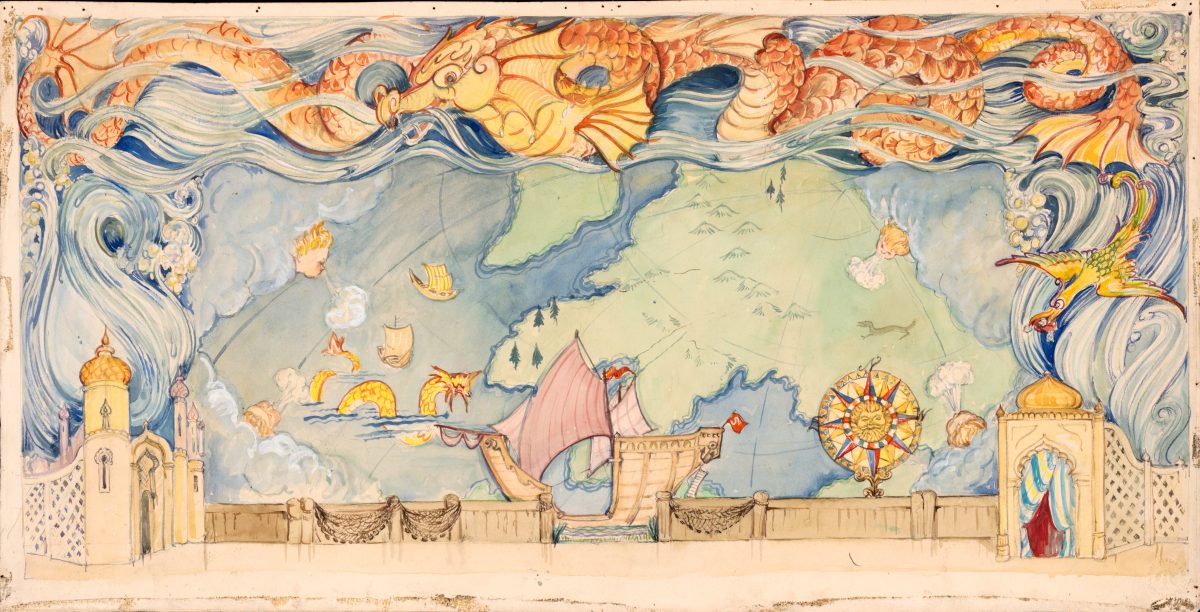

Courtesy of the Louisiana State Museum.

Set design for Krewe of Athenians Ball, watercolor and pencil on paper, 1960. The ball theme was "Return of Sinbad the Sailor."

Sharing a first name with her father, Louis Andrews no doubt showed exceptional artistic promise at a young age. She entered Newcomb College in New Orleans in 1917 at age sixteen on a scholarship and enrolled in the prestigious art program. The choice of schools could not have been more perfect for Louis, since one of the goals of the pioneering curriculum was to nurture the talents of the college’s female students and equip them to support themselves as artists upon graduation.

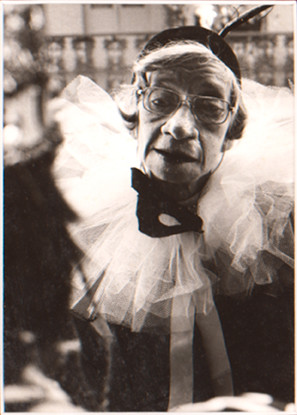

Louis Fischer at her last Mardi Gras, 1974. Courtesy of the Louisiana State Museum.

Louis dipped her toes into the exotic fairyland of Carnival design before she even achieved her degree. She was chosen to execute designs for at least two elite and demanding New Orleans Carnival krewes, the Twelfth Night Revelers and the Knights of Momus, both of which traced their roots back to the 1870s. Louis created the whimsical illustrations that were reproduced on the covers of the ball programs for these two krewes in 1921. Printed krewe invitations and programs at this time were often so lavishly delineated that they were saved as souvenirs and eventually made their way into museums and archives.

Upon graduating from Newcomb in 1921, Louis’s drafting skills were immediately put to excellent use. She went right to work dreaming up fanciful designs for costumes and parade floats for a pair of the leading krewes of the day, Rex and the Krewe of Proteus. Within a year, she added Momus to that list and in effect became the artistic director for these three prominent old-line krewes while still a young woman in her twenties.

After Louis married Lawrence Fischer in 1926, the couple made a home in the heart of the French Quarter in one of the historic Pontalba Buildings. This notable pair of twin block-long apartment buildings, completed in 1850 and 1851 on Jackson Square, was home to an impressive cadre of forward-thinking artists and writers whose work was integral to the Southern Renaissance. Among the luminaries whose company the Fischers kept were William Faulkner, Sherwood Anderson, William Spratling, and Lyle Saxon.

It was also at this time that Louis launched the most fruitful and enduring phase of her career. She began a prolific relationship with the W. H. Bower Spangenberg company, a scenic design firm in business since 1889 that produced elaborate sets for many Carnival balls. Spangenberg also provided staging for trade shows, conventions, and other extravaganzas. Louis quickly earned the position of chief scenic designer for Spangenberg, a title she kept until her death in 1974.

Set design for the Krewe of Venus ball, watercolor and pencil on paper, 1957. The ball theme was “John James Audubon—The Naturalist,” and the setting was a typical Louisiana swamp. Members of the court were costumed as various birds. Courtesy of the Louisiana State Museum.

In 2017, in recognition of the unparalleled length and diversity of Fischer’s career, the Louisiana State Museum’s Carnival Collection made a historic acquisition of forty-six of Louis Fischer’s colorful set designs, along with nearly six hundred preliminary sketches on tracing paper. Considering the length of Fischer’s employment at Spangenberg, even a collection of this size represents just a small part of her massive lifetime output.

Even though they were meant as working drawings for Spangenberg’s production crews, each of Fischer’s set designs can be appreciated as a finished work of art. Painted in watercolor on paper up to three feet wide, they contain a level of detail and inventiveness that speaks to her mastery of the medium. The Spangenberg company gave Louis a wide berth to express her imagination within the confines of krewe themes, which commonly included fairy tales, nursery rhymes, mythology, historical events, exploration of exotic lands, and games and entertainment. Familiarity with this many subject areas meant that Louis remained well read and curious.

In a typical year, she may have been asked to illustrate Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (one of her favorite tales), a raucous circus theme, a gypsy revel, a history of the cinema, or the untamed depths of the ocean. She imbued each of her watercolor paintings with the same degree of care. After all, the final result of her work would be a complete theatrical setting that could be as wide and as tall as the biggest stages in New Orleans.

Set design for the Krewe of Athenians, watercolor and pencil on paper, 1969. The ball theme was “Bal des Artistes” and paid homage to the famous Moulin Rouge. Courtesy of the Louisiana State Museum.

The vast grouping of Fischer’s pencil sketches acquired by the Louisiana State Museum gives some clue of her artistic method. Working only in pencil, Fischer drafted the highly detailed design on one side of the transparent sheet and then turned it wrong side up to trace the design onto durable watercolor paper. For more modest set designs, especially those that were bilaterally symmetrical, Fischer could choose to draw just half the set, trace over it once, and then reinvert the original tracing right side up and transfer the design again to the other half of the watercolor paper. Shortcuts like this were an essential element in a prolific artist’s toolbox.

Several years before her death, Fischer returned to designing parade floats for several old-line krewes while continuing her work for Spangenberg. With her passing in 1974, the era of the artistic designer—one individual whose vision influenced the look of Carnival parades, costumes, balls, and printed materials—began to wane. However, since Carnival is at its core an artistic celebration and an indelible part of Louisiana’s culture, it remains important to preserve the work of artists like Louis Fischer to provide documentation of past artistry and perhaps inspiration to designers of the future.

—

Wayne Phillips is the Curator of Costumes and Textiles at the Louisiana State Museum.