Summer 2017

All Access Past

The Louisiana State Museum prepares to publish colonial documents collection online

Published: June 8, 2017

Last Updated: October 15, 2018

What makes these manuscript records of the French Superior Council (1714–1769) and the Spanish Judiciary (1769–1803) so important? The Superior Council was both the governing body and high court of France’s Louisiana colony and was for many years presided over by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, founder of New Orleans and the king’s representative. While virtually all of its administrative records were removed to France before or at the time of the Louisiana Purchase, records pertaining to the colony’s inhabitants remained in Louisiana. The judicial records, both civil and criminal cases, fell into this category, as did some ten thousand notarial acts—contracts between and among individuals, corporations, and other entities. Under Spanish rule, the Superior Council was replaced by a cabildo, or city council, with similar functions and authority; Spanish notaries continued the civil law practices of their French predecessors without missing a beat. With the growth of commerce and population under the Spanish came a proportionate increase in the creation of notarial and judicial records.

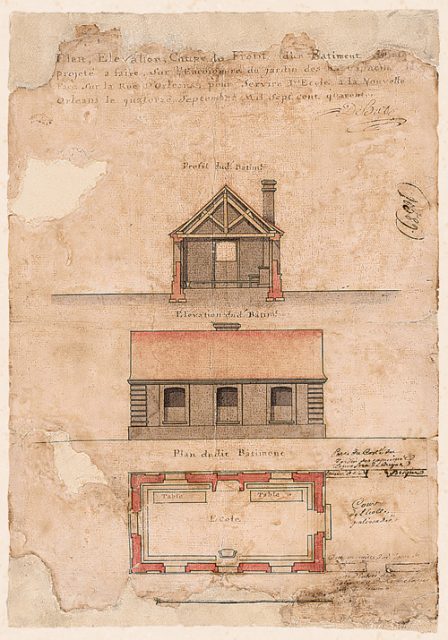

This water-colored drawing – created by the artist Alexandre De Batz in 1740 – is entitled “Plan, Elevation, Section and Profile of the Brick Building Projected to Be Built on the Corner of the Garden of the Rev. Capuchin Fathers, Facing on Orleans Street, to Serve as a School.” The new structure would have replaced a nearby ruined house, where Capuchin Father Raphael de Luxembourg had established a school for boys in 1725, but it was never built. Courtesy of the Louisiana State Museum Historical Center and the Louisiana Historical Society

These records document Louisiana’s colonial era in astounding detail, recording sales of enslaved persons as well as real estate, laying bare disputes within families and between neighbors, and revealing the social and commercial underpinnings of the colony. They tell thousands of individual stories that, taken together, document the daily life of Louisiana’s first permanent African and European inhabitants, as well as aspects of their relations with Native tribes. They are a largely unplumbed store of source material that offers countless opportunities for study in history, sociology, language and linguistics, law, cultural anthropology, and other humanities fields.

“When I began studying colonial Louisiana, I was lucky enough to live in New Orleans and that made it possible for me to visit the archives and write early Louisiana history,” says Emily Clark, Clement Chambers Benenson Professor in American Colonial History at Tulane University. “Scholars who lived elsewhere had two choices: find a way to come to New Orleans for a limited time with the records, or give up and choose to study a different place. They often chose the latter. The result has meant that there is far less written about colonial Louisiana than there is about colonial New England. I predict that the digitization of the archives will change that.”

From the time that the Louisiana Historical Society (LHS) took custody of this archive in the 19th century, local researchers have recognized its value. Efforts to preserve the documents played a large role in the creation of LSM in 1906; the museum has housed the collection since its early years, first in the Cabildo and now at the Louisiana Historical Center in the Old US Mint in New Orleans. Over time, archivists, catalogers, and translators have sought to make the documents comprehensible to those who consulted them. Through various translations, English-language abstracts, and published summaries in LHS’s journal, The Louisiana Historical Quarterly, the contents of the collection were partially accessible but difficult to use. In the 1930s and 1940s, the federal Works Progress Administration provided great assistance with dedicated workers who cataloged, translated, and indexed documents. While the collection became more usable over the years, the acidity of the original ink, environmental conditions, and early archival practices meant that by the current century, the collection had become extremely fragile. After years of preliminary groundwork, in 2007 LSM’s then director of collections Greg Lambousy, along with other LSM staff and the Louisiana Museum Foundation, began formulating a plan to digitize the collection and improve archival storage. Fundraising and outreach brought in many partners, including the Ella West Freeman Foundation, the Joe W. and Dorothy Dorsett Brown Foundation, LHS, the French-American Chamber of Commerce, the Forum on European Expansion and Global Interaction, and Lycée Français de la Nouvelle-Orléans. In 2013 a $275,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities provided a substantial boost to the project. The project team included many essential members from outside the museum: Howard Margot, the lead consultant, who had supervised a similar digitization project at the New Orleans Notarial Archives; contract scanners and indexers, including Melissa Stein, Erin Roussel, Jennifer Long, and Bryanne Schexnayder; and scholars who served as advocates for the collection, including Emily Clark and University of Notre Dame historian Sophie White.

Besides its priceless collections of colonial era manuscripts and maps, the Louisiana Historical Center houses a wealth of primary and secondary source materials in a wide range of media. Courtesy of Louisiana State Museum, Photo by Mark J. Sindler

Thanks to the contributions and efforts of the project team, generous funders, and countless others, the digitization of LSM’s Colonial Documents Collection will soon have a profound impact on the study of New Orleans, the state of Louisiana, the South, the nation, and the Atlantic World. From anywhere, researchers will be able to access these stories through high-resolution scans and take advantage of new keyword indexes that correspond to topics of historical interest today.

Any celebration of the project should also recognize the importance of these records to succeeding generations of Louisianans. From the notaries who wrote and guarded them, to the lawyers who used them, to the families who tapped them to validate legal claims, all saw the significance of these documents. The first administrators of the LHS were aware that “access to the records was central in another way to all history of the French and Spanish in North America,” says Susan Tucker, a consulting archivist who also served on the project. According to Tucker, the story of access to the judicial documents merits honoring local historians of the past, such as early-20th-century lawyer Henry Dart, who came to work with them every day. His contemporary, the writer Grace King, knew them to be the key to understanding the past of New Orleans and Louisiana. Moreover, those who cared for and worked with the collection also appreciated what they could reveal about our nation. One of the translators opined that the records were “the most wonderful collection of original documents in the United States.”

LSM plans several events to launch its Colonial Documents Collection website in the fall of 2017, just in time for the tercentennial of New Orleans.

The Louisiana Historical Center is located at the Old U.S. Mint, 400 Esplanade Ave., New Orleans. For more information, visit LouisianaStateMuseum.org.

Sarah-Elizabeth Gundlach is curator of maps and manuscripts/colonial documents coordinator at the Louisiana State Museum, The Old U.S. Mint, Louisiana Historical Center.