Spring 2018

Make It Good: An Interview with Leah Chase

Zella Palmer talks with the culinary legend and 2018 LEH Humanist of the Year

Published: March 1, 2018

Last Updated: January 30, 2019

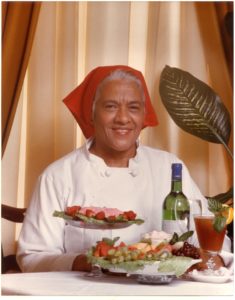

Courtesy of the Amistad Research Center

Leah Chase Collection.

You came to New Orleans as a young woman with big hopes and dreams to study.

Twelve years old.

Twelve years old.

I had to come here to go to high school because my daddy always wanted us to go to Catholic schools and there were none for African Americans in Madisonville. I had to come here under the assistance of the [Sisters of the] Holy Family. I learned a lot from them. A whole lot. They sacrificed a lot to help young black women. I appreciate that, I really do.

But I see things today and sometimes it’s frightening, because young people don’t understand. They don’t look back. If a person dies for you to have what you have, do you know how important that is? That is the sacrifice. Martin Luther King and many other people died for what they believed, to help you along the way. Then you should remember that and try to do the best that you can do. Appreciate the people who went before you. You have different cultures, different beliefs. That’s okay. But work together.

“I live by the three rules my daddy gave me. Pray, work, and do for others. You can’t go wrong.”

Unfortunately what happens sometimes in America is that we commercialize history. Martin Luther King is now, in a lot of eyes, just as a person who had a dream, and that’s it.

It’s more than a dream. He was a special kind of person.

So was your husband, Dooky. Sometimes people forget to mention his name, but I feel like this award should be for both of you, because right beside you—

Right. Because I could not be what I am today had it not been for Dooky. I loved this business. He did not. He was a musician. That’s what he loved, but he sacrificed his life to come in here to help his mother, and then to help me, because he knew I loved it.

To me, that’s a great thing. To give up what you love to help somebody else up. Dooky took care of everything. I do the work in here, I do all the publicity and all this-that-and-the-other, and the cooking. But he took care of everything else. Now he still is doing that.

You see, it takes everybody to make the world turn. Like you have this pretty blouse.

Thank you.

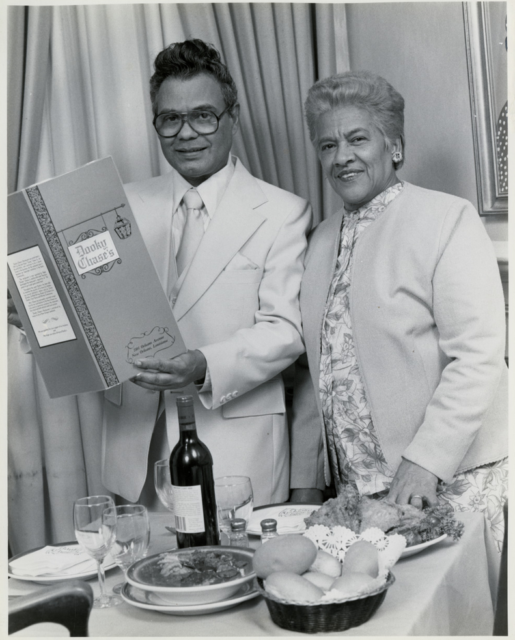

Portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Chase, 1965. Courtesy of the Historic New Orleans Collection. Photo by Harold Baquet.

You work every day. You don’t have time to hand-wash and press that. But I could do that for you. You see, I’m helping you get up, and that’s what we’re supposed to do. Do whatever we can to do to raise somebody else up. That is the thing you have to do

I know when you started out with your husband, with your in-laws, it wasn’t necessarily your plan to give as much as you did, and for this restaurant to be so important and integral to the community.

You know, when I came in here, this restaurant was popular. My mother-in-law and father-in-law were popular people. They didn’t have all of the restaurant knowledge that they needed, because they were not allowed in restaurants. They were just trying to make a living. But they liked people. They tried every way they could to help people. People will remember you for that, if you just try to help other people. I tried to do the same thing.

You’ve been named the 2018 LEH Humanist of the Year. Who were some unknown humanists that never got the recognition that they deserved?

There are so many people that really do things. What I do is I help them and they help me. People like Delores Aaron, who’s now gone on. She helped me. Carmen Morial, who was a great supporter of this restaurant. She died at 101 years old. Those people didn’t get their just due. They worked in the community. They worked hard to uplift children and uplift people. There are too many to really name. You know Richard Colton? He does a whole lot. People pay him no attention, but he helps people get through college.

There are many people who really do things, and they don’t get the awards. To me that’s sad. You get all the awards, and there’s so many people that want to help you out. Patrick Taylor and his wife, Phyllis, they worked hard to help other people. The Landrieus. They’ve been working in the community for years. We have a lot of people that really work. Teachers like Irene Green. They just did what they had to do. I rode on their coattails. I listened to them. They helped me. I tried to help them where I could. To me, that’s important. To help other people.

Back row – (left to right) Edgar “Dooky” Chase IV, Gretchen Chase, Edgar “Dooky” Chase, III, Eve Marie Haydel, Victor Haydel, Robert Haydel; Middle row – (left to right) Tracie Haydel Griffin, Stella Chase Reese, Emily Haydel; Front row (seated) – Leah Chase. Courtesy of Tracie Haydel Griffin.

What do you hope for young people?

I would like [young people], especially young African Americans, to learn the power of the vote. Because that is so important. That makes you involved—to cast a vote involves you in the system that you need. That to me is so important. The vote is important. So I try to get that out. You know, you got to get people to those polls. So much you have to do. Just so much.

When you’re alone, who is Leah Chase?

A pathetic person. Cry a lot. Think a lot. I think about my daughter [Emily Chase Haydel passed away in 1990], think about my husband. The hard thing is, you cannot do a thing about it. The pain is there. It’ll never go away. You have to learn to live with it, and that is hard. When you feel like that, you get up. Put on your clothes and get out. Get among other people. See what’s going on with them. That’s the thing I like to do. I can’t sit down and cry. Nothing will bring them back. Death is terrible to me. Death is frightening. Nobody ever came back to tell you what it’s like. You really don’t know what it’s all about.

You just try to do the best you can to make you a good person. I feel this way, honey, about the world. I feel the creator, God, gave us this world. He gave it to us. Said, It’s yours. Do whatever you want with it. Make it good. Do whatever you want with it, and get back to me. That’s not easy. It’s hard to do. You have to make sacrifices. You have to think about other people. What is better for everybody in the world? That’s not easy to do. I pray a lot. I keep going.

What are your hopes for your children and grandchildren?

That they will be good leaders. That they would always do for others. That they will always pray, because you need that spiritual help. You can’t get by without it. Say some kind of prayers, for heaven’s sakes. Just keep going.

Pouring Oysters by Gustave Blache, III. Courtesy of the artist.

What are your hopes for Catholics?

For Catholics? Well, they’re learning so much. You know, when I came up as a Catholic, we were not allowed in a non-Catholic church. We were not allowed there. Now we can do that. We can work with the Methodists, the Baptists. Now we can all work together. We can all praise and honor one God. You believe what you believe, I believe what I believe, but it’s all to make this world a better world.

What are your hopes for New Orleans?

A whole lot. A whole lot. This city is on the move, but we have to get people involved. Everybody has to do something to make it work. You know, when they took down those statues, everybody in their minds thinks, it’s a racial thing. In my mind, it was the political move for the mayor. A strong political move. Good for him, it was really good. We have to look at that and be able to move with him. If he moves up, we want to go up, too. Just have to work together. That’s all I hope to do, is to work together.

“There are many people who really do things, and they don’t get the awards.”

I don’t know about all that, but food binds people. When I meet people, the first thing ask them is “What do you eat in your country?” If I know what you eat, I know a lot about you. I learn to appreciate your food, and I want you to appreciate mine. Food is so important. All the civil rights people, they made a difference over a bowl of gumbo and some fried chicken. When they met here [at Dooky Chase’s Restaurant], that’s all they had. But they did that. I feel like we changed America over a bowl of gumbo and some fried chicken. You see, you feed people and they’re ready to work. They’re happy and go on.

Years from now, when we gather to lift a glass to you, what do you want people to say?

That’s a good question. I would like them to say that I tried my best to help other people, and to make a difference. I think this all the time. Everybody can’t be a leader, but you can be a good follower. Maybe you can’t lead, but you can help a leader get up. That will uplift you, too. To me, that’s important. People. That’s the most important thing.

What would you say is your life’s motto?

I live by the three rules my daddy gave me. Pray, work, and do for others. You can’t go wrong.

Amen. Perfect. Thank you, Miss Leah.

Thank you.

Zella Palmer is chair of the Dillard University Ray Charles Program in African-American Material Culture.