Fall 2018

The Matrix of Creativity

Reading Tom Dent and renegotiating Black aesthetics in the new New Orleans

Published: August 28, 2018

Last Updated: February 28, 2019

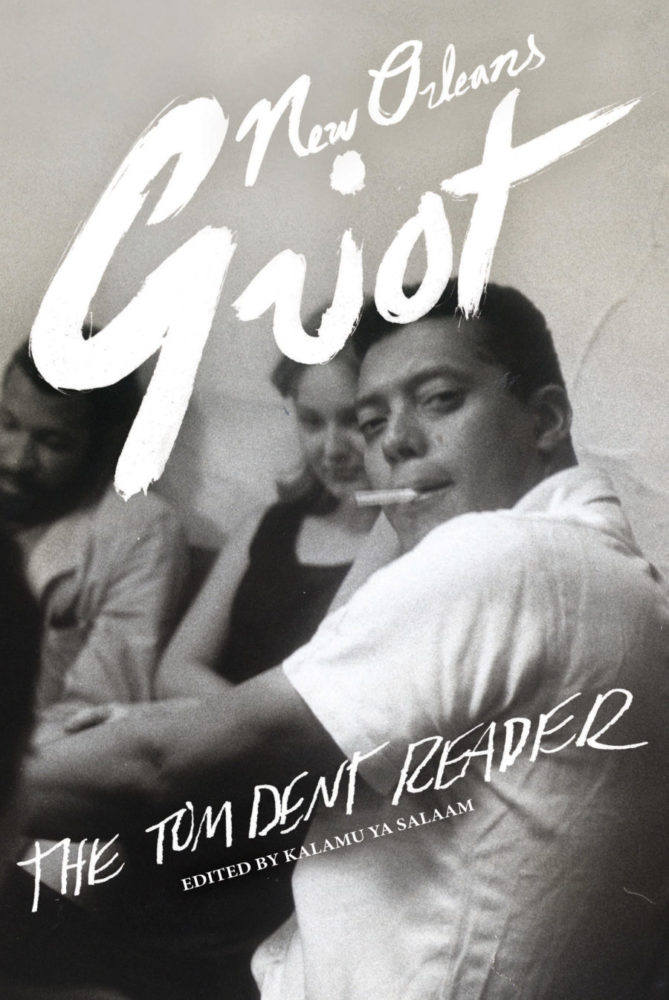

Courtesy of University of New Orleans Press.

New Orleans Griot: The Tom Dent Reader, edited by Kalamu Ya Salaam.

Born to a solidly upper-middle-class black family, Dent’s father served as the president of Dillard University from 1941 to 1969. Dent himself attended Morehouse College and was fully prepped to take his place in what W. E. B. Du Bois called Black America’s “Talented Tenth.” Yet Dent centered and exalted the lives of poor and working class Black New Orleans in his creative work and practice. It is these people who are the cultural glue that ensured the culture’s survival through the centuries—and it would be these same folk, Dent believed, who would carry the story into the future. “Griot is no honorary title, nor a glib marketing phrase,” Salaam writes. “[I]t is a life-long commitment to documenting and passing on the unique vibrancy of Black New Orleans culture.”

At times, throughout the large but easily navigable volume, it is as if Dent is speaking directly to the present moment of identity crisis in New Orleans. The city, in its three hundredth year, has reached a tipping point from which there is no turning back, with small and large daily changes setting the stage for the next century or more of history. How to resist what needs resisting and embrace what needs embracing requires a discernment for which the deep study of Dent’s work can prepare us.

To be truly radicalized is to understand rebellion not as a mere reaction to someone else’s actions but as the total expression of the collective Self. How the collective genius of Black people and Black New Orleans can be specifically employed as a roadmap through the uncertain future is distilled with stunning clarity in this expertly crafted text. To understand how New Orleans became a “matrix of creativity,” as Dr. Jerry Ward describes it in a 1986 interview with Dent featured in The Tom Dent Reader, we have to take a look back—further back than the triangular diagram of spices, rum, and human beings that history books usually present as the origin story of Black Americans.

Kalamu Ya Salaam posits Dent as the greatest writer New Orleans has ever produced.

The cosmology of the Bambara, a Mandé people who made up a larger portion of the enslaved population in Louisiana than anywhere else in the Western Hemisphere, is described in some detail in Gwendolyn Midlo Hall’s Africans in Colonial Louisiana. “According to this cosmology, the universe, emerging from a moving void, undergoes a slow process of acquiring voice and vibration that eventually evolves into light, sound, creatures, actions, and human sentiments. The order of this universe is expressed arithmetically through numbers one through seven as is outlined in Cheikh Anta Diop’s, Civilization or Barbarism. Native to Mali and later stolen from the Senegambia region, the Bambara’s cosmology is designed to be transported across distance.” In Flash of the Spirit, Robert Farris Thompson examines the word Mandekan word woron. Literally meaning to “get the kernel,” it encapsulates the process needed to master speech, song, music, or any aesthetic endeavor. Thompson goes on to outline the Mandé concept of reason, which relies on a balance of opposites, badenya (the conformist) and fadenya (the innovator). This tension between tradition and innovation produces a culture always in flux, always moving, changing, and reinventing the world. It is the retention of these key African cultural concepts by Black New Orleanians that makes the city the perpetual site of what’s new and next on the horizon.

Following a short stint in the military, Dent moved to New York in the early sixties and joined Umbra Writers’ Workshop, a collective of Black writers trying to establish professional creative lives for themselves in the city. Dent’s participation in Umbra would set the stage for the work he would do at home with Free Southern Theater (FST), a community theater group founded in Jackson, Mississippi, by Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee organizers Doris Derby, Gilbert Moses, and John O’Neal. By 1968, FST had relocated to New Orleans and established acting and writing workshops, out of which grew BLKARTSOUTH and later Congo Square Writers’ Union.

In “Beyond Rhetoric: Toward a Southern Black Theater,” Dent is frank about the challenges and internal conflict the Free Southern Theater and other similar groups faced with regard to those who saw their presence in New Orleans as a sincere but temporary post, and those who were locally born or resident and wanted the FST to be grounded in a permanent commitment to the city. Dent describes a “collision course” between the desire for FST to be Southern, to be Black, and the desire of some within the organization to engage in and be supported by white-liberal, New York funding structures. It is a dilemma currently faced by more and more Black artists born in New Orleans and choosing to base their practices here: a neoliberal nightmare in which Black Aesthetics are being choked by nonprofit funding models, while the traditional social structures used to sustain the community are being dismantled daily by gentrification and displacement. As we head into this tricentennial celebration, it is Dent that Black artists, Black people, and all people who find themselves in residence in New Orleans should be reading now.

New Orleans Griot: The Tom Dent Reader

Edited by Kalamu Ya Salaam

520 pages $28.95

University of New Orleans Press

Kristina Kay Robinson is a writer, curator, and visual artist born and raised in New Orleans. Her artistic and curatorial endeavors include Khalid Abdel Rahman’s “A Disappearance” and Republica: Temple of Color and Sound, an aesthetic reimagining of New Orleans and the Gulf Coast as free unincorporated territory within the borders of the United States. She is the coeditor of Mixed Company, a collection of short fiction and visual narratives by women of color. Her writing in various genres has appeared in Guernica, The Baffler, The Nation, and Elle.com, among other outlets.