NOLA 300 Music

New Orleans Expatriates: Satchmo and Lil Wayne

People abandon their midwestern suburbs. They escape their very important northeastern jobs. They come to New Orleans for a taste of freedom represented, in part, by the artistic work of the greatest trumpet player who ever lived and the “greatest rapper alive.”

Published: August 30, 2018

Last Updated: April 15, 2019

The recreational department, lacking either the budget or the will to provide a healthy recreational experience, confined us to a brick building at the corner of Carrollton and Walmsley Avenues. This was Lafayette Elementary, which was empty for summer break, except for a half-dozen counselors and maybe 150 kids with nothing to do. As with most New Orleans public schools, including my own high school, McDonogh 35, there was no playground, just a large gravel yard. It was very similar to the one Morgan Freeman and Tim Robbins frequented in The Shawshank Redemption. But I digress. I always assumed the school board couldn’t afford grass. Or maybe they couldn’t afford to pay someone to cut the grass. Or perhaps someone decided we didn’t deserve grass.

At summer confinement, the counselors and participants mostly hunkered in darkened hallways to avoid the heat. The free camp was run by the city, and this was New Orleans, so all the kids were black like me. Nobody with means would allow their children to suffer such conditions. But parents who couldn’t afford daycare during the break had no choice. They knew their children would probably be safe.

Sometimes we passed the quiet moments with song. One of the children, a boy of about twelve, did a spot-on impersonation of Louis Armstrong. Occasionally, fights broke out between kids. Bad feelings lingered. But when that young man sung “What A Wonderful World,” we all calmed down.

Louis Armstrong went to segregated schools. This probably sounds normal because he was school-aged in the early twentieth century. But my own high school was segregated in the 1990s. I visited there not long ago. It’s still segregated. The private uptown schools allow a few children of color, but they’re segregated, as well.

Armstrong grew up in poverty. His neighborhood, which is a stone’s throw from present-day City Hall, was called the Battlefield. At age twelve, he shot a gun into the air. He was thrown into the Colored Waifs Home for Boys, where, as the story goes, they fed him nothing but stale bread and honey. This is where he met his first mentor, who taught him how to properly blow a horn. A few years later, Armstrong would get a job on a steamboat, playing music for pleasure seekers on the way to St. Louis. He would never again be arrested in New Orleans or restricted to a diet of honey sandwiches.

Dwayne Michael Carter Jr., better known as Lil Wayne, went to Lafayette Elementary. I didn’t know who he was at the time, so it’s entirely possible that he was among the kids at my camp the summer I worked there, but I can’t swear it. If I ever meet Mr. Carter one-on-one, I promise I’ll ask. The first time I heard a Lil Wayne song was when my future brother-in-law, who was about twelve, popped a mixtape into my car cassette deck and said, “You got to hear this.” This was in the mid-’90s. I loved rap, but, honestly, I didn’t know what I was hearing. The future sounds like gibberish to the average man.

About a decade later, this brother-in-law slid another Lil Wayne album, Tha Carter II, into my car compact disc player. This time I heard him. To this day, I play the album intro, “Fly In,” while jogging up St. Charles Avenue. It makes me run faster, full of pride in being from New Orleans, or as Lil Wayne calls our hometown, “the Creole Cockpit.” I’m still thankful to my brother-in-law, who was born on the same day as Armstrong and who, for many years, had the same mini-dread hairstyle as Lil Wayne.

When Lil Wayne was twelve, he accidently shot himself. He lived in Hollygrove, where he may have thought a gun was needed for self-defense. This was back when he was the wunderkind of a group of rappers on Cash Money Records, which was headed by his mentor Birdman, whom Lil Wayne referred to as his real dad. A few years later, Lil Wayne left New Orleans. His career blossomed.

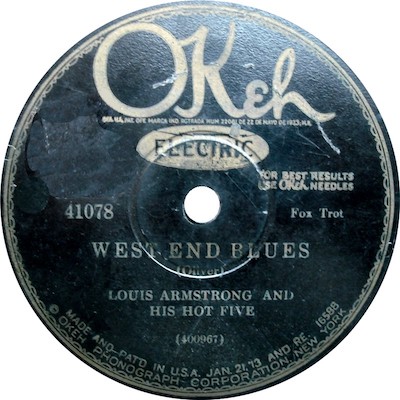

I had a pocket-sized music history book. Pick a page and learn about the biggest artists in the history of popular music. The author wrote that while Elvis was an important figure, Louis Armstrong was arguably the most important artist of the twentieth century. He virtually invented the jazz solo, which undid the belt-and-suspenders strictures of popular music. Then that quintessentially American music—jazz—swept the globe. Armstrong himself became an American ambassador. A New Orleans ambassador.

In the mid-2000s, it seemed like every black man in New Orleans under the age of twenty-five adopted Lil Wayne’s hairstyle. His mop of dreads seemed illogical for our hot, humid weather. But I knew I only thought so because I was over the age of twenty-five. Today, Lil Wayne has sold over one hundred million albums. This puts him in range of artists like Barbara Streisand, Bruce Springsteen, and Frank Sinatra.

Both Armstrong and Lil Wayne did short stints in jail after leaving New Orleans. I think of this as the revenge of a spurned city. Who from the Battlefield never smoked a joint? Who from Hollygrove never kept a gun? Who from New Orleans truly cared one way or the other?

But Armstrong and Lil Wayne had the good fortune of being arrested outside of the incarceration capital city of the world, nestled like a jewel within the incarceration capital state of the world. My brother-in-law has been in jail for years. He will be in jail for years. I’ve visited him. When he was free, he enjoyed weed. They may have caught him with a gun. Today, they feed him bread and mayonnaise and meat product.

Armstrong and Lil Wayne did what many African Americans have done. Some millions of us left the south for the north in the waves of the Great Migration. Some others of us—Nina Simone, Josephine Baker, James Baldwin—left America for Europe to gain freedoms they could not have in a nation under apartheid.

When Armstrong settled in Chicago in the 1920s, he found that for the first time in his life, he didn’t have to do manual labor to make ends meet. He could just play. I sometimes wonder what would have happened to them both if they had stayed. Perhaps Armstrong would have wound up waiting tables in the Riverbend. Maybe Lil Wayne would have worked a dump truck for a time.

If you take out the bridges, New Orleans is an island. On this swampy bit of land, fantasies blaze forth. People abandon their midwestern suburbs. They escape their very important northeastern jobs. They evacuate their Los Angeles condos. They flock from their Florida retirements. They come to New Orleans for a taste of freedom represented, in part, by the artistic work of the greatest trumpet player who ever lived and the “greatest rapper alive.” But those men are gone from here.

Maurice Carlos Ruffin is a recipient of an Iowa Review Award in fiction and was the winner of the William Faulkner–William Wisdom Creative Writing Competition for Novel-in-Progress. His work has appeared in Virginia Quarterly Review, AGNI, Kenyon Review, Massachusetts Review, and Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas. A native of New Orleans, he is a graduate of the University of New Orleans Creative Writing Workshop and a member of the Peauxdunque Writers Alliance. Maurice’s first novel, “We Cast A Shadow,” will be published by Random House in 2019.