NOLA 300 Music

High Society and the Myth of the Jazz Festival

Newport may not be Shakespeare’s Forest of Arden, but the film’s plot revolves around the myth of the festival as a way to turn sorrow to joy and bring the major players to romantic bliss

Published: September 3, 2018

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

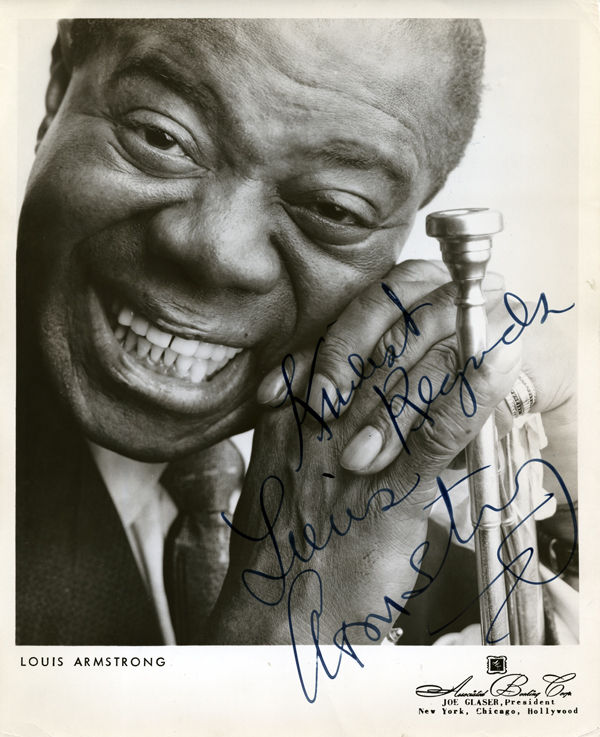

Signed picture of Louis Armstrong.

The film opens with Armstrong and his band partying on a bus on their way to play what turns out to be a music festival based on the Newport Jazz Festival. The atmosphere is joyous, celebratory, and Armstrong is dressed to the nines in a Panama hat and tailored suit as he sings in between puffs of a blunt-looking cigarette stuffed into an elegant holder. His band, the All-Stars, joins in the merriment, with drummer Barrett Deems playing a calypso beat on bongos and the others playing acoustic instruments and singing the chorus, as Armstrong acts as omniscient narrator for the tale that is about to begin:

Just dig that scenery floating by / We’re now approaching Newport, Rhode I / We’ve been, for years, In Variety / But, Cholly Knickerbocker, now we’re going to be /

In high, high so-

High so-ci-

High so-ci-ety

Armstrong takes long puffs on his cigarette, letting the smoke waft in the air Cheshire Cat-style, as he continues the story:

I wanna play for my former pal / He runs the local jazz festival / His name is Dexter and he’s good news / But sumpin’ kind of tells me that he’s nursing the blues . . . // He’s got the blues ’cause his wife, alas / Thought writing songs was beneath his class / But writing songs he’d not stop, of course / And so she flew to Vegas for a quickie divorce. // To make him sadder, his former wife / Begins tomorrow a brand-new life / She started lately a new affair / And now the silly chick is gonna marry a square.

In four stanzas, Armstrong lays out the plotline for the film. Then he takes it a step further, indicating that he’s going to enter this world of privilege, cast his spell, and trick all the players into doing his bidding. This Shakespearean turn allows him to stand outside of the society crowd, but also to exist above it, manipulating the actions of the players:

But, Brother Dexter, just trust your Satch / To stop that wedding and kill that match / I’ll toot my trumpet to start the fun / And play in such a way that she’ll come back to you, son

K. Dexter-Haven, played by Bing Crosby, is a wealthy socialite who married Tracy Samantha Lord (Grace Kelly), an heiress to a coal fortune. Dexter’s love of jazz irritated her (“You could have been a serious composer! What did you become? A jukebox hero!”), and she divorced him. Tracy now intends to marry George Kitteridge (John Lund), a real stiff, but Dexter is still in love with her. Tracy accuses Dexter of scheduling the jazz festival “to conflict with my wedding.”

Matters become more complicated when Mike Connor, a celebrity reporter played by Frank Sinatra, arrives on the scene and woos the clearly uncertain Tracy.

Armstrong comments on Dexter’s progress in between scenes. When Dexter plays the song he wrote for his ex, an up-tempo jazz number accompanied by Armstrong and the All-Stars, Tracy sees it as a provocation and becomes furious. Armstrong’s comment on the tune is that it’s “good for the feet,” but “nothin’ for the heart.” Then, when Dexter sings a love song to Tracy’s little sister, “My Little One,” with Armstrong playing in the background, Louis comments “Right song, but the wrong gal.”

When Armstrong realizes Dexter is losing out to both George and Mike, he notes that his horse is in third place. “What we need,” he concludes, “is a little change-of-pace music.”

Armstrong begins to play a gorgeous ballad. Dexter, in his dressing room, joins in, singing “I Love You, Samantha.” Tracy hears this in her room and undergoes an immediate transformation.

“Now we’re gettin’ warm,” says Armstrong approvingly.

At a party the night before the wedding Tracy gets drunk and is caught in a compromising situation with Mike while Dexter and Armstrong sing the raucous duet “Now You Has Jazz.” Next morning, the outraged George walks away from the altar, and Dexter impulsively takes his place at the ceremony to remarry his sweetheart, who, aided by Armstrong’s ministrations, has fallen back in love with him. As the solemn wedding march plays, Armstrong and the All-Stars interrupt with a jazz version. The staid socialites all turn toward Armstrong, smiling, rocking to the music and waving their arms in happiness. Even Tracy, who frowns at first, finally bursts into a smile. “End of story,” Armstrong announces. We never actually see the festival, but the joyful response to the band’s performance at the wedding is presumably the prelude to the festival itself, which is scheduled for that day.

Newport may not be Shakespeare’s Forest of Arden, but the film’s plot revolves around the myth of the festival as a way to turn sorrow to joy and bring the major players to romantic bliss. This fiction was inspired by producer George Wein’s Newport Jazz Festival, which tobacco heir Louis Lorillard and his wife Elaine organized in 1954. They hired Wein to book performers like Armstrong, and the success of the event was clearly the template for the story line of High Society.

Newport begat the rock festivals of the late 1960s, epitomized by the Monterey Pop Festival in California and Woodstock in New York. These events spoke to a desire to bring the participants back to a state of grace, a return to Eden best expressed in a line from Joni Mitchell’s “Woodstock”—“We’ve got to get ourselves back to the garden”—or in the ads for Woodstock itself, promoted as not just three days of music but three days of peace and music. The idea that these rituals, enacted by musicians, create a magical space and bring a collective joy to fans has only gathered strength.

Armstrong did not live to participate in George Wein’s greatest festival achievement, founded in his own birthplace and the birthplace of jazz. Wein wanted to bring the Jazz Festival to New Orleans, but when he was first approached by the city in 1963, it was still enforcing strict segregation laws. By the end of the 1960s New Orleans was integrating, and Wein was able to establish the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, a celebration of Louisiana culture that Armstrong would have been proud of, and is still going strong nearly five decades after his death. Each year, multiple marriages take place there.

John Swenson is a writer with an extensive background in New Orleans music dating to his 1974 cover story on Dr. John in Crawdaddy magazine. During his career he has worked as an editor at at Crawdaddy, Rolling Stone, Circus, Stereophile, Rock World and OffBeat and as a columnist at United Press International and Reuters. He has written 14 published books including biographies of Bill Haley, The Who, Stevie Wonder and The Eagles and co-edited the original Rolling Stone Record Guide with Dave Marsh. He is also the editor of the Rolling Stone Jazz and Blues Album Guide. His most recent book New Atlantis: Musicians Battle for the Survival of New Orleans is about musicians returning to the city after hurricane Katrina. His writing has been awarded three first prizes by the New Orleans Press Club.