Alone but Not Forgotten

Published: March 1, 2020

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

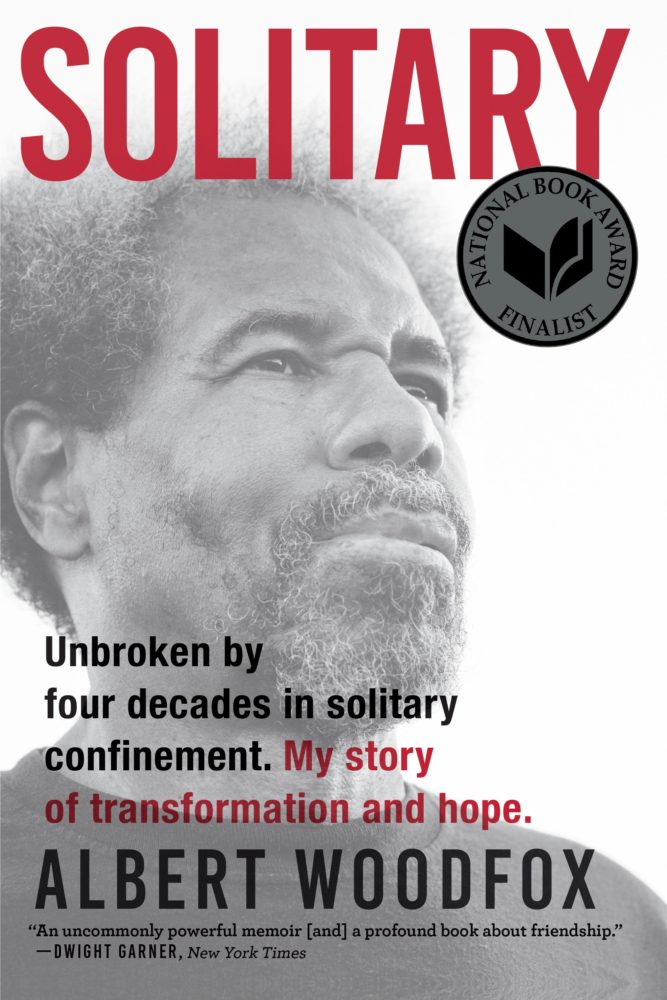

Grove Press

SOLITARY © 2019 by Albert Woodfox.

The following excerpts from Solitary are reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Grove Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.

By the early eighties Herman, King, and I knew we were forgotten. The Black Panther Party no longer existed. (The organization is said to have officially ended operations in 1982.) We’d written many letters to organizations asking for help. I can’t ever recall getting a letter in reply. I was disappointed. In some ways I felt betrayed. We were forgotten by the party, by political organizations, by people involved in the struggle.

I felt frustrated. We were dismissed or ignored by the numerous lawyers and legal aid organizations we wrote, asking them to look at our cases. To us it was obvious there was a grave miscarriage of justice in our situation. When we didn’t get any replies to our letters, though, we knew we had no choice but to continue our struggle on our own. We became our own support committee. We became our own means of inspiration to one another.

When the federal government took over running Angola in the seventies as a result of the Hayes Williams lawsuit, one of the concessions the Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections had to make in the consent decree was to create a way to review prisoner housing at Angola. For prisoners housed in segregation, the lockdown review board—which we called the “reclassification,” or “reclass,” board—was supposed to review each prisoner’s housing assignment every 90 days to determine if he still needed to be locked down, or if he could be released into the general population. The reason given on paper for locking down me and Herman in CCR was, “Original reason for lockdown.” Prisoners always had the option to attend these hearings, and for years I went to them, even though it was immediately clear to me there was no way a prisoner could “work” his way out of CCR. There were no guidelines established that if followed by prisoners, would require the reclass board to move them to less-restricted housing. Prisoners were simply moved around at the whim of the officials in charge. If officials needed a cell in CCR, they moved a CCR prisoner into a dorm in the main prison, and someone new moved into his cell. We saw men who were behavioral problems, men who had recent write-ups for violence against prisoners, and men who had just been in the dungeon get out of CCR in this way. We saw a prisoner who pulled a knife on the warden get released from CCR. Herman, King, and I—with no behavioral problems and few write-ups—would never be released.In the early years, they kept us there out of hatred and for revenge. They had talked themselves into believing that Herman and I killed Brent Miller and that King was involved. (From the day King arrived at Angola, in May 1972, his file said he was in CCR because he was being “investigated” for the murder of Brent Miller, even though Miller was killed a month before King arrived at the prison.) Then, they kept us locked down because of our political beliefs. They knew through our actions over many years at CCR that we weren’t regular prisoners, that we were different. We constantly wanted to change our environment. We were able to unify prisoners. We believed in the principles of the Black Panther Party. Years later this was confirmed when warden Burl Cain made statements under oath that we were being held in CCR because of our “Pantherism.” In a 2008 deposition he said he wouldn’t let me out of CCR even if he believed I was innocent of killing Brent Miller. “I would still keep him in CCR,” he said. “I still know that he is still trying to practice Black Pantherism, and I still would not want him walking around my prison because he would organize the young new inmates. I would have me all kind of problems, more than I could stand, and I would have the blacks chasing after them [Woodfox and Wallace]. He [Woodfox] has to stay in a cell while he is at Angola.”

The CCR lockdown review board was usually made up of a major or captain and a reclassification officer. Normally, the prisoner would stand before the officers in front of a table while his case was being reviewed. When I went before the board they didn’t even look up while they signed the paper indicating I was staying in CCR. I was never once asked a question at a reclass board. I never once had the impression that anyone ever opened my file. They’d be talking among themselves about hunting and fishing or some other subject and slide my signed paperwork keeping me in CCR to the corner of the table. Sometimes they’d be signing the paper while I was walking into the room. Once in a while the major on duty would say, “Why do you keep coming to the board, Woodfox? You know we can’t let you out.” Even the tier guards knew it was a waste of our time to go to the board meetings. They’d call down the tier to tell us the board was meeting and ask us if we wanted to go. If we said yes they’d say, “Why? You ain’t getting out.” At some point, I stopped going to the reclass board. It was a hassle to get all the restraints on just to stand before the table for a few seconds. After I quit going the tier sergeant would bring the signed paper keeping me in CCR and put it between the bars in my cell every 90 days.

We didn’t have the wars on the tier in the eighties that we had in the seventies. The inmate guards were long gone; there were black correctional officers hired; and, after a decade, many of the people working the tiers hadn’t known Brent Miller. A lot of guards, white and black, spent 12 hours a day on the tier and got to know prisoners and didn’t hate them. They worked at Angola to feed their families and pay their bills. They could see that Herman, King, and I weren’t bullies, we weren’t violent, we weren’t racist. We were polite. Many told us they were taught in the Department of Corrections training academy that we were examples of the “worst of the worst.” They were shocked when they got to know us. Some officers told me and Herman they thought we were innocent; they didn’t believe we killed Brent Miller.

There were always guards, however, who enjoyed the absolute power and control they had over another human being, guards whose whole life and identity were tied up in the way they acted out against prisoners. One of those guards once opened my cell door so another prisoner could jump me. This prisoner was a real bully and troublemaker and everybody knew he and I didn’t get along. One day when he was out on his hour he came and stood in front of my cell door. I got up and started to walk to the cell door. I knew something was about to happen or he wouldn’t be standing there. Then my door opened. He tried to come into my cell; we fought and I beat him up. I was written up for fighting and sent to the dungeon, even though I was obviously defending myself. I wrote to the warden, asking him to investigate the guard who had opened my cell door. I never received a response. Years later the state tried to say this write-up showed how violent I was, to use it as an excuse for keeping me in CCR.

SOLITARY © 2019 by Albert Woodfox.