Marc-Antoine Caillot

This biographical entry covers Marc-Antoine Caillot, a young clerk sent to Louisiana by the French Company of the Indies, who chronicled his journey to and experiences in Louisiana between 1729 and 1731.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

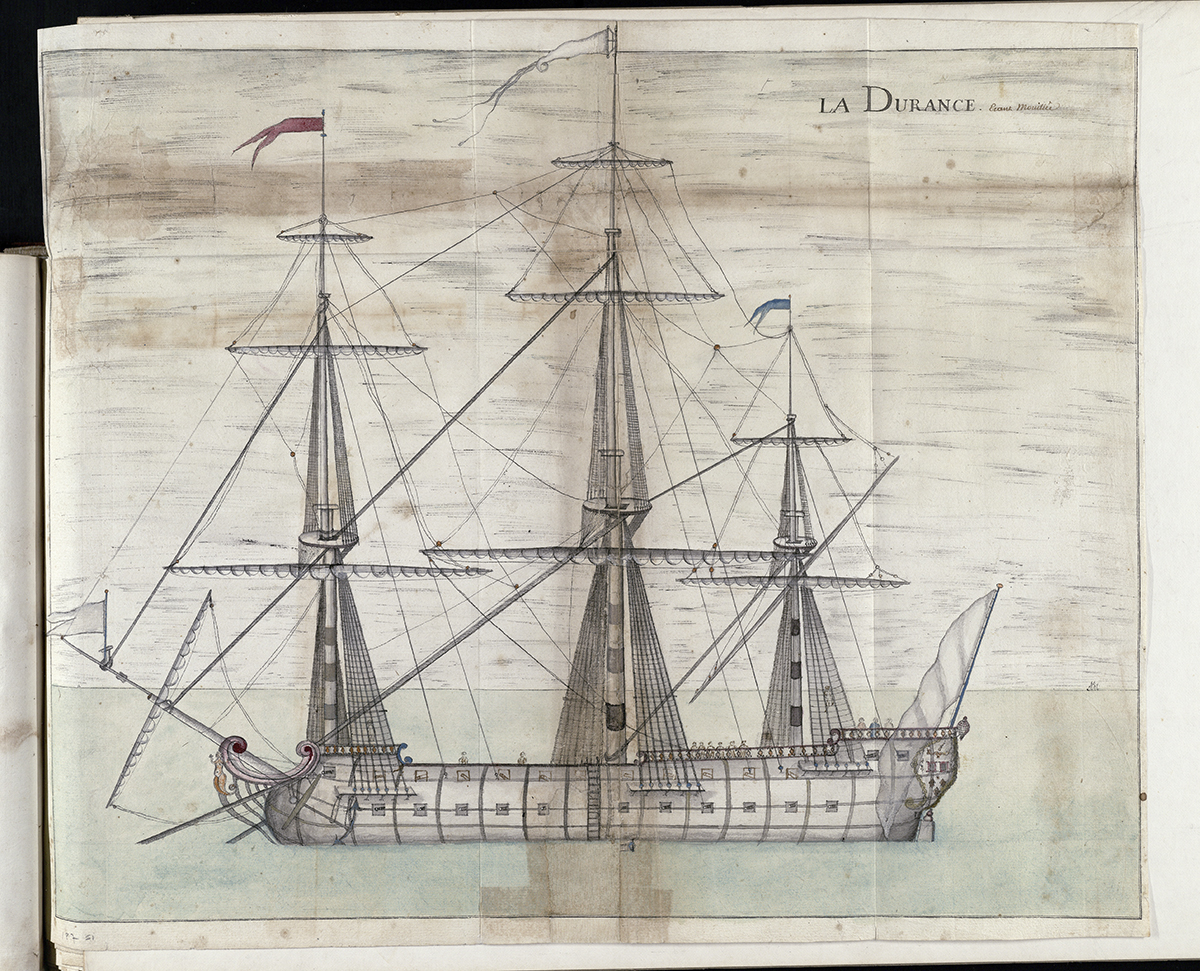

Marc-Antoine Caillot's watercolor rendering of the Durance, the ship that carried him from France to Louisiana in 1729.

Best known for having penned a witty, intimate, uncensored, and sometimes outright scandalous account of his travels to and residence in Louisiana from 1729 to 1731, Marc-Antoine Caillot spent nearly thirty years in the employ of the French Company of the Indies (Compagnie des Indes). His career, which began in Paris in the 1720s and ultimately spanned three continents, was an upwardly mobile one, made possible in large part by his extensive familial and professional connections.

Early Life and Family Ties

The second of fourteen children born to Pierre Caillot and Marie-Catherine Blanche, Marc-Antoine Caillot was baptized in Meudon, France, on June 4, 1707. Named for his godfather, Marc-Antoine Balligant, a footman in the Château de Meudon, Marc-Antoine spent his early years in a royal household headed by Louis XIV’s eldest son, Monseigneur le Dauphin, who died of smallpox on April 14, 1711. Caillot’s father, uncles, and maternal grandfather were in service at Meudon to the Maison du Roi (King’s Household), a royal institution whose entourage of religious, military, and domestic personnel served the king and his heirs.

When Louis XIV died in 1715, royal power shifted away from the king’s households to Paris, home of the king’s regent, Philippe II, duc d’Orléans. For Caillot this shift broke his noble family’s multi-generational chain of service in royal households, but did not exclude him from favor. Rather than following in his father’s footsteps as a valet in the Maison du Roi, Caillot received a patronage position with the French Company of the Indies.

A Company Man and a Louisiana Memoir

His first exposure to the company’s global trade network was as a simple scribe, or copy clerk, in the company’s Paris offices. He began his training there around 1728 and received his first overseas commission—as a bookkeeping clerk in the Louisiana colony—in early 1729, when he began composing a personal memoir documenting his travel and life experiences in the French Atlantic World. He left Paris on February 19 and, after a three-week overland journey to the Atlantic coast, boarded the Durance, a merchant vessel bound for the Gulf Coast. His 184-page memoir, originally titled Relation du voyage de la Louisianne ou Nouvelle France fait par le Sr. Caillot en l’année 1730 and translated and published for the first time in 2013 as A Company Man: The Remarkable French-Atlantic Voyage of a Clerk for the Company of the Indies by The Historic New Orleans Collection, provides an intimate account of the Atlantic crossing. He captures his romantic escapades and bawdy encounters; his fear of death via shipwreck; and his experience of purse-lightening maritime rituals. He also provides a window on the world of travel by horseback, covered barge, and tall sailing ship in the first decades of the eighteenth century.

But it is his account of time spent in New Orleans from 1729 to 1731 that is Caillot’s most significant contribution to the historiography of French colonial Louisiana. Caillot spent just two years as a bookkeeping clerk based in the company’s headquarters, a one-block district bounded by the Place d’Armes/St. Peter, Chartres, Toulouse, and Levee Streets, yet he recorded scenes that significantly expand our understanding of life in French colonial Louisiana. From Caillot readers learn how newly arrived African captives were disembarked from slave ships at the mouth of the river and loaded into smaller vessels manned by company-owned slaves for their journey upriver to the company’s west bank plantation (present-day Algiers Point). We learn how early New Orleanians celebrated Carnival (cross dressing, then as now, proved popular), and how the city’s residents reacted to news of Natchez Indian attacks that left more than 230 colonists dead and destroyed the colony’s dreams of creating a tobacco empire.

In the spring of 1731, after just twenty months in New Orleans, Caillot returned to France via the Saint-Louis. His tenure cut short by the retrocession of Louisiana from company to Crown—a reversal sparked by losses to the Natchez Indians, Caillot wasted no time in joining the ranks of company employees stationed in the more profitable outposts of the Indian Ocean. On January 14, 1732, he boarded yet another ship, a five-hundred-ton frigate named the Atalante, this one bound for Pondicherry, India.

Upward Mobility in India

Once in India Caillot moved rapidly through a succession of posts, rising from bookkeeping to head clerk, then from assistant merchant trader to trader—posts which took him to trading sites in Chandernagor, Patna, and Balassor, and finally to the highest administrative post in the company’s Indian Ocean sphere: member of the Pondicherry Superior Council. Much of his upward mobility can be attributed to his marriage, in 1736, to Marie-Claire Lucas, the great-niece of Pierre de Saintard, who served first as syndic (shareholder’s representative), from 1723 to 1738, then as a company director, from 1739 to 1759. Caillot’s marriage to Lucas was short-lived. In 1737 she died shortly after giving birth to the couple’s only child, Marie-Madeleine, but Caillot continued to benefit from his connection to the Saintard clan throughout his career. He remarried in 1740, this time to Marie-Anne Coquelin, widow of a fellow merchant trader and daughter of a company ship captain. The two had no children.

In the 1750s war that began on the European Continent between rival European powers spread to North America and the Indian Ocean. The Seven Years’ War, also known as the French and Indian War, struck India in 1757 with the arrival of an English military fleet. Within weeks of its outbreak, British forces, led by Colonel Robert Clive, had overtaken the French at Chandernagor, prompting an evacuation of the settlement. Wounded during the defensive campaign, Caillot remained in Chandernagor until early 1758, when he evacuated via the Nossa Senhora dos Prazeres. Caillot never reached his final destination. Instead he died at sea on February 24, 1758. At the time of his death, Caillot’s net worth totaled 74,000 livres (French pounds), making him one of the wealthiest men employed in the company’s Indian Ocean network.