Natchez Revolt of 1729

The Natchez massacre of 1729 was the culmination of failed French colonial diplomacy with the Natchez Indians.

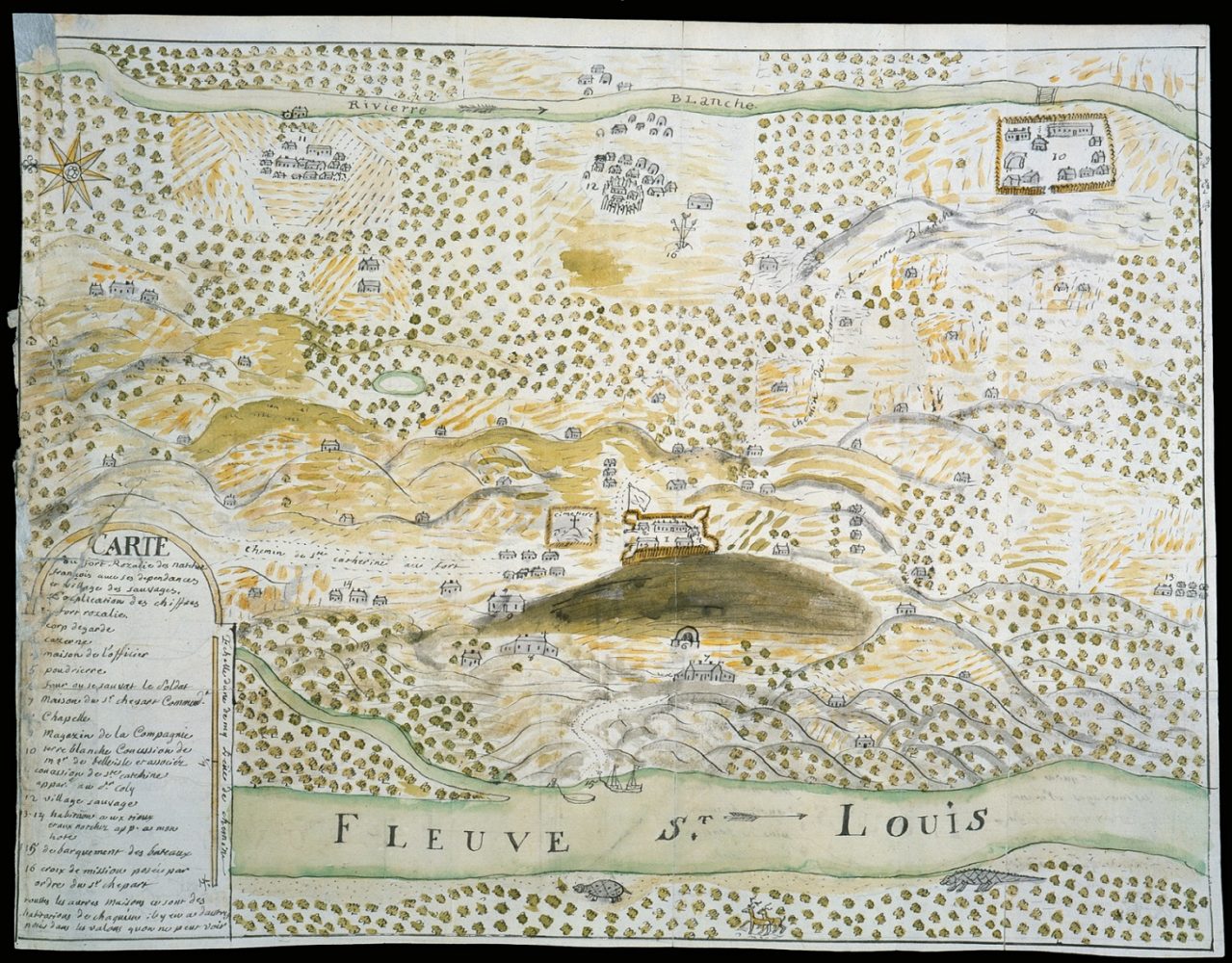

Newberry Library

This map from around 1750 depicts the settlement of Natchez and the surrounding area, including Fort Rosalie.

The Natchez revolt of 1729 was the culmination of failed French diplomacy with the Natchez Indians that lived in several villages near present-day Natchez, Mississippi. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, French administrators of the Louisiana colony found the powerful tribe to be friendly and open to sharing land for trade purposes. However, after a few years that included a series of diplomatic missteps, the French, in efforts to develop agriculture, pressured the Natchez to forfeit their lands and threatened to drive them off. The Natchez responded with a massacre that led to the deaths of more than two hundred settlers and soldiers, as well as the end of the Natchez nation.

First Encounters

At the time of the first French contact with the Natchez people in the late seventeenth century, the tribe—unique among major Native American tribes in the southeast—was based on a complex chiefdom with a rigid class system. Members worshipped the sun as their only god, and the supreme chief was called the Great Sun. Succession to power was matrilineal in that the Great Sun was always the son of a royal female chief. The Natchez lived in at least six villages in the vicinity of the Natchez Bluffs. One estimate puts the population of the Natchez nation at three thousand in the year 1700.

In 1682 René-Robert Cavalier, sieur de La Salle traveled from Canada down the Mississippi River to its mouth, and he claimed the river and all of its tributaries in the name of France. In the years that followed, efforts to establish a successful colony led the French government to charter private companies, such as the Company of the Indies, to lead settlement and development of the new lands, but mismanagement and British competition hamstrung the fledgling colony. It was during this difficult period that the settlement near present-day Natchez was founded (in about 1716). The region was considered attractive for its potential trade opportunities with the Natchez (along with the prospects of blocking such opportunities from the British) and for its flood-free fertile ground, which was suitable for agriculture. Just west of Great Village, where the Great Sun resided, the French built a small fortification described as “merely a plot twenty-five fathoms long by fifteen broad, enclosed with palisades, without any bastion.” They named it Fort Rosalie in honor of the wife of Count Jerome Phelypeaux Pontchartrain, minister of the colonies of France under Louis XIV. The small settlement slowly grew as concessions were granted to clear and farm surrounding lands. One source lists the non-indigenous population of the immediate area in the autumn of 1729 as three officers, twenty-five soldiers, 200 male colonists, 80 female colonists, 150 children, and 280 enslaved Africans.

Revolt

The tragic events of 1729 were not spontaneous; they were preceded by serious but smaller-scale altercations in 1715, 1722, and 1723. In these skirmishes, Frenchmen and indigenous people were murdered, which only spurred retaliation by the opposing party. Relations between the factions were often strained, and the tension only increased as the settlers evolved from trading with the Natchez to farming. In 1725, Tattooed Serpent, the Natchez war chief who had worked to preserve peace, died. Then in 1729, a man, whom many consider to be the instigator of the revolt, arrived as commander of Fort Rosalie by order of Commandant-General Etienne de Perier. Commander de Chépart (or Detcheparre in some accounts) was remembered as a tyrant who mistreated Natchez and settlers alike. His fatal mistake was demanding on short notice that the Natchez move from the site of their Great Village so that a plantation might be established there. Some speculate that he was acting on behalf of Perier, who sought a personal holding at Fort Rosalie. The ultimatum was inconceivable to the Natchez, whose high temple, which held the bones of their royal ancestors, occupied the village. The Natchez tribe saw no option but to rid its lands of the aggressors.

A contemporary account describes the scene:

“First they [the Natchez] divided themselves, and sent into the Fort, into the Village, and into the two grants, as many Savages as there were French in each of these places; then they feigned that they were going out for a grand hunt, and undertook to trade with the French for guns, powder and ball, offering to pay them as much, even more than was customary and in truth, as there was no reason to suspect their fidelity, they made at that time an exchange of their poultry and corn, for some arms and ammunition which they used advantageously against us. … Having thus posted themselves in different houses, provided with the arms obtained from us, they attacked at the same time each his man, and in less than two hours they massacred more than two hundred of the French.”

Most reports list those killed as 144 men, 35 women, and 56 children. Other French women and children, along with enslaved Africans, were captured, and a few managed to escape. Speculation persists as to the active role of enslaved Africans in the affair as well as the collusion of other minor indigenous tribes in the region. Small scuffles that resulted in more deaths occurred in the weeks following the massacre.

Aftermath

News of the affair immediately paralyzed the Louisiana colony with fear, as further uprisings were expected on all sides. Perier had the nearby peaceful Chaouchas tribe slaughtered as a warning to others. A force consisting mostly of the Choctaw led by the Chevalier de Loubois was sent against the Natchez in February 1730. They managed to free many of the captives and invest the fortified village before the entire tribe slipped away in the dark of night, crossing the Mississippi River and marching through the swamps to the Sicily Island area in present-day Catahoula Parish. There the Natchez were able to exist for a year until they were attacked once again. Most members then went to the Natchitoches area, where many of them were captured in the fall of 1731 and sold into slavery in St. Domingue. A few survivors scattered to the Chickasaw and Cherokee tribes and were assimilated.

Repercussions of the Natchez massacre affected the Louisiana colony for years. Promising agricultural concessions in the outlying districts were abandoned for fear of Indian attacks. The Company of the Indies, after losing its most flourishing settlement, decided to give up its trade monopoly in the colony as a financial disaster; all trade reverted to the jurisdiction of the French crown in 1732. In turn, trade opportunities were thus made available for all enterprising Frenchmen, at least in theory.