The Canary Islands

Louisiana’s Isleños trace their roots to a storied archipelago

Published: September 1, 2020

Last Updated: June 27, 2023

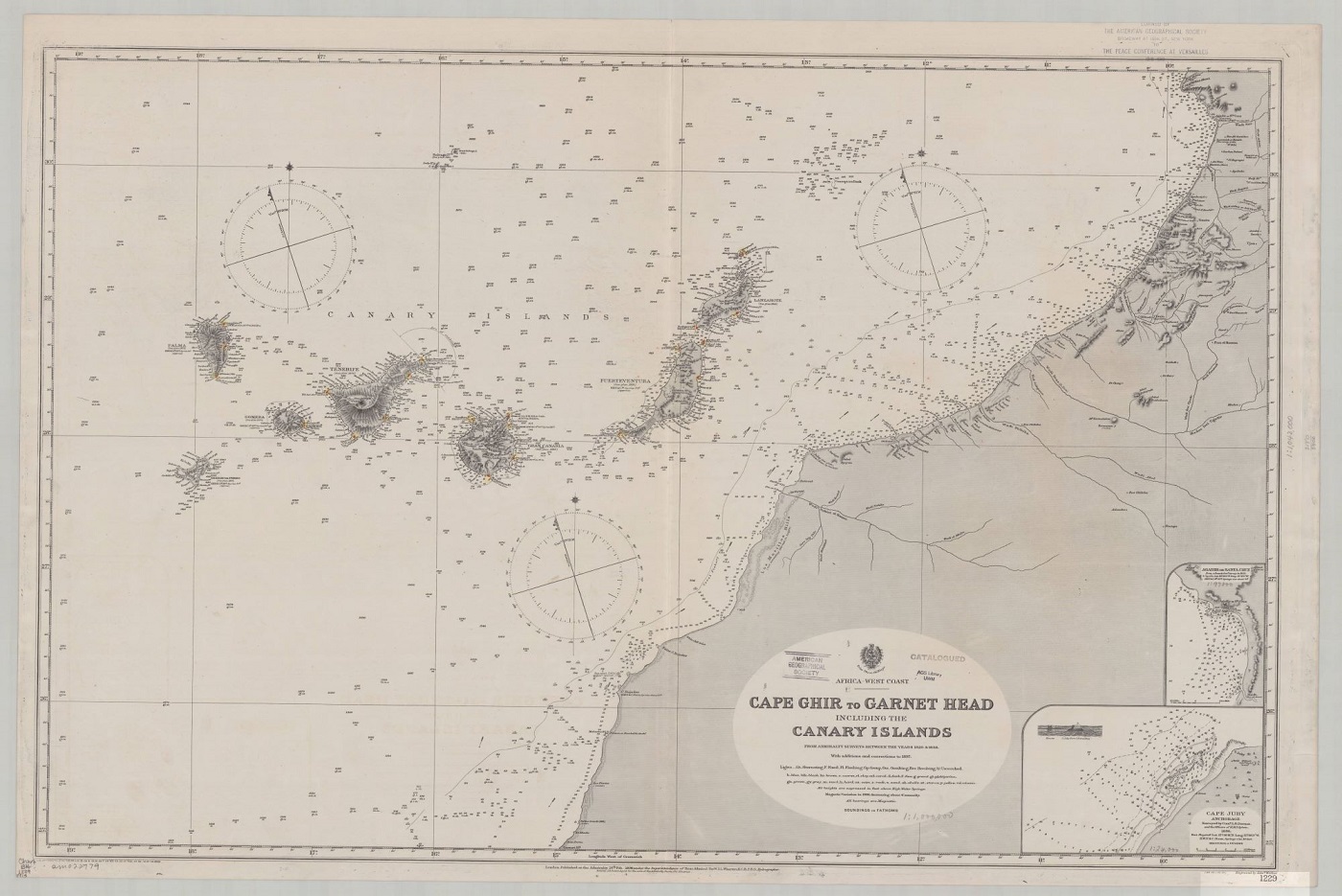

Wikimedia Commons

An 1898 British admiralty chart showing the Canary Islands off the northwest coast of Africa.

No one knows who the first Canary Islanders were. Juba II of Mauretania, a Roman-allied North African king and son-in-law to the famous Cleopatra, sent an expedition to the Atlantic islands, which found no people but mysterious ruins and a profusion of dogs, after whose Latin name, canis, the islands were named. (Canary birds were then named after the islands.) Archaeological finds of Roman-made goods tell us that a permanent population had either been missed by Juba’s men or established itself at some subsequent point in Roman times. Genetic and linguistic evidence indicates that these people, generally known as Guanches, came from the nearby coast of Africa in what is now Morocco and Western Sahara. The Guanche were one of the first casualties of the colonial ventures of the Age of Exploration. Portugal, Genoa, and the Kingdom of Majorca sniffed around the Canary Islands in the fourteenth century, but it was the Crown of Castile that gradually conquered them over the course of the fifteenth century. Many Guanche were killed or enslaved, but enough assimilated into the arriving population to make it culturally distinct from that of the mainland. One particularly significant legacy of the indigenous inhabitants is the whistled language Silbo Gomero. The Guanche had been able to reproduce the rhythm of their language in whistles that carried across the rocky islands, and the new Castilian speakers adapted this system to their own tongue.

The Canary Islands were perfectly placed to serve as a jumping-off point for the trans-Atlantic voyages that made the Spanish Empire possible. Their convenient location, combined with farming of sugarcane, wine grapes, and red-dye-producing cochineal beetles made the islanders rich, a prosperity only occasionally punctuated by attacks from Spain’s strategic rivals. As trade patterns within the Spanish Empire changed in the eighteenth century, the island’s wealth waned. Many residents emigrated to Spain’s New World possessions, including Spanish Luisiana, whose governor Bernardo de Gálvez, eager to bolster Spanish strength in the colony, lured settlers with promises of land and opportunity.

Settling most notably in St. Bernard Parish but also in Ascension and Assumption Parishes, the Isleños followed the familiar pattern of attempting to acclimate to their surroundings and neighbors while also preserving their identity and traditions. Neighboring Franco- and Anglo-American populations looked down on the use of Spanish, and today Isleño Spanish is spoken by a relatively small number of older speakers. Other cultural traditions have fared better, with traditional Isleño songs, folklore, and cuisine finding strong advocates in recent generations. In 1976, the Los Isleños Heritage and Cultural Society was established; today, the group maintains the Los Isleños Museum and Historic Village, providing a home for Isleño cultural preservation and research and a venue for—what else?—the annual cultural festival held in St. Bernard Parish each spring.

Today, the Canary Islands form a largely autonomous province of Spain after a short-lived independence movement following the fall of the Franco regime in 1975 failed. An ancient rivalry means the territory has two capitals: Las Palmas de Gran Canaria and Santa Cruz de Tenerife. The compelling history, natural beauty, and sunny climate of the islands have made them a popular tourist destination. One of the most popular festivals in the islands is, of course, Carnival—a celebration in which they are joined in spirit each year by their distant cousins across the Atlantic.

Chris Turner-Neal is the managing editor of 64 Parishes. His ancestors were primarily from colder islands.