Angola: Fact and Fiction

Plentiful stories about the prison have cemented misunderstandings

Published: June 1, 2020

Last Updated: June 1, 2023

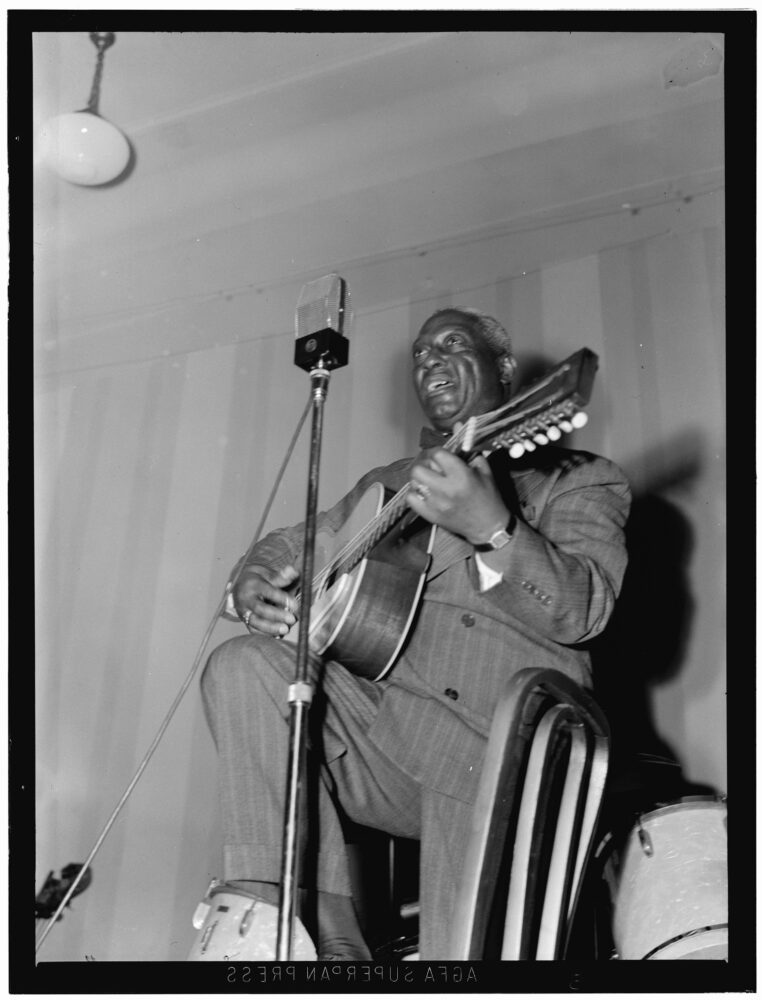

Photo by William P. Gottlieb, Library of Congress

Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter, pictured here performing at the National Press Club ca. 1938, didn’t need to sing his way out of prison—just to wait for time off for good behavior.

The name Angola was given because of the origin country of many of the enslaved people who worked the original plantation.

This is inaccurate for a number of reasons. Angola, on Africa’s southern Atlantic coast, was a major source for slave traders, but as part of the Portuguese Empire, it tended to supply enslaved laborers to Brazil, also a Portuguese possession, with North American shipments restricted primarily to Charleston and Savannah in the years after the American Revolution. Even given the possible importation of enslaved Angolans to Louisiana though, the legal transatlantic slave trade was quashed in the early 1800s, with the US Congress legislating a total ban on international slave trading in 1808. Plantation owner Isaac Franklin did not purchase the properties later consolidated as “Angola” until the 1830s, by which point the American slave trade, in which Franklin made his initial fortune, was essentially all domestic. Franklin referred to one of his plantations as Angola, though Angora, an old rendering of Ankara in Turkey, also shows up in contemporary records; both names reflect a trend of naming plantations after faraway lands, real or imagined. (Franklin also owned Killarney, a neighboring property named for a town in Ireland, and Loango, a plantation presumably named for the major slave trading port located in what is now the Republic of Congo.) By 1880, surviving documentation all reflected the name “Angola” familiar today.

Lead Belly sang his way out of prison.

The story speaks to Louisiana’s conception of itself: whatever sins we may commit, our love of music unites us—and redeems us, to an extent. The legend goes that Huddie Ledbetter, universally known as Lead Belly, was incarcerated at Angola but sang so movingly to the governor, or sang in the governor’s presence, or wrote such a beautiful song, that O. K. Allen pardoned him. Repeated in contexts as august as Dr. John’s patter introducing the cover of Ledbetter’s “Goodnight Irene,” often cited as the song that melted the governor’s heart, this story is so widely believed that it’s the one thing people know who know nothing else about Lead Belly.

Alas, the truth is significantly less poetic: Ledbetter got time off for good behavior. Louisiana law provided for prisoners who had behaved in accordance with prison policies to be released early, with the important caveat that if they reoffended within the state, they would have to finish their commuted sentence for the first crime before beginning any sentence for the next. Ledbetter’s was one of six commutations signed on July 20, 1934, and one of 179 in the whole year, for crimes including murder, manslaughter, shooting at a dwelling, and carnal knowledge—such commutations were common enough to be essentially routine. Lead Belly’s music, cherished as it is, didn’t soften a governor—but it didn’t need to.

Outlaw and jailbreaker Charlie Frazier was welded into his cell.

Charlie Frazier was the most common of the various names under which one of the most prolific outlaws of Depression-era Louisiana was arrested—and the one associated with another Angola myth. Frazier, a stick-up artist in the Bonnie and Clyde vein, was a key figure in a 1933 jailbreak that shocked the Angola and Louisiana powers-that-were. This jailbreak did lead to the first cellblock being built at Angola, with the new Red Hat building (named for the red-painted straw hats worn by inmates) serving as a stricter adjunct to the barnlike dormitories that had housed all inmates before the escape. While Frazier was ultimately captured in Texas and slung into one of the new cells in 1936, it wasn’t welded shut for the simple reason that Frazier had to be taken to trial in St. Francisville for charges related to the deaths of Camp E Capt. John Singleton and foreman James W. Fletcher, Angola employees, and trusty guard Arnold Davis, all of whom were killed in the jailbreak. Newspaper reports and Frazier’s prison record reveals that he was almost immediately put back in the “red cap line,” at Camp E, from which he had escaped in 1933. Capt. C. C. Dixon, a long-time employee whose descendants also worked at the facility, was remembered as the only person Frazier would speak to after his rearrest; Dixon never corroborated the lurid but unlikely detail of the welded cell. For men used to the dormitories, the cells may have felt welded shut, but the jailers never literally threw away the key.

Marianne Fisher-Giorlando is a professor emerita at Grambling State University and the outside researcher for the Angolite, the inmate-edited and -published magazine of the Louisiana State Penitentiary. Chris Turner-Neal is the managing editor of 64 Parishes.