Summer 2021

Sick As a Horse

The Great Epizootic devastated New Orleans’s equine population

Published: May 28, 2021

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

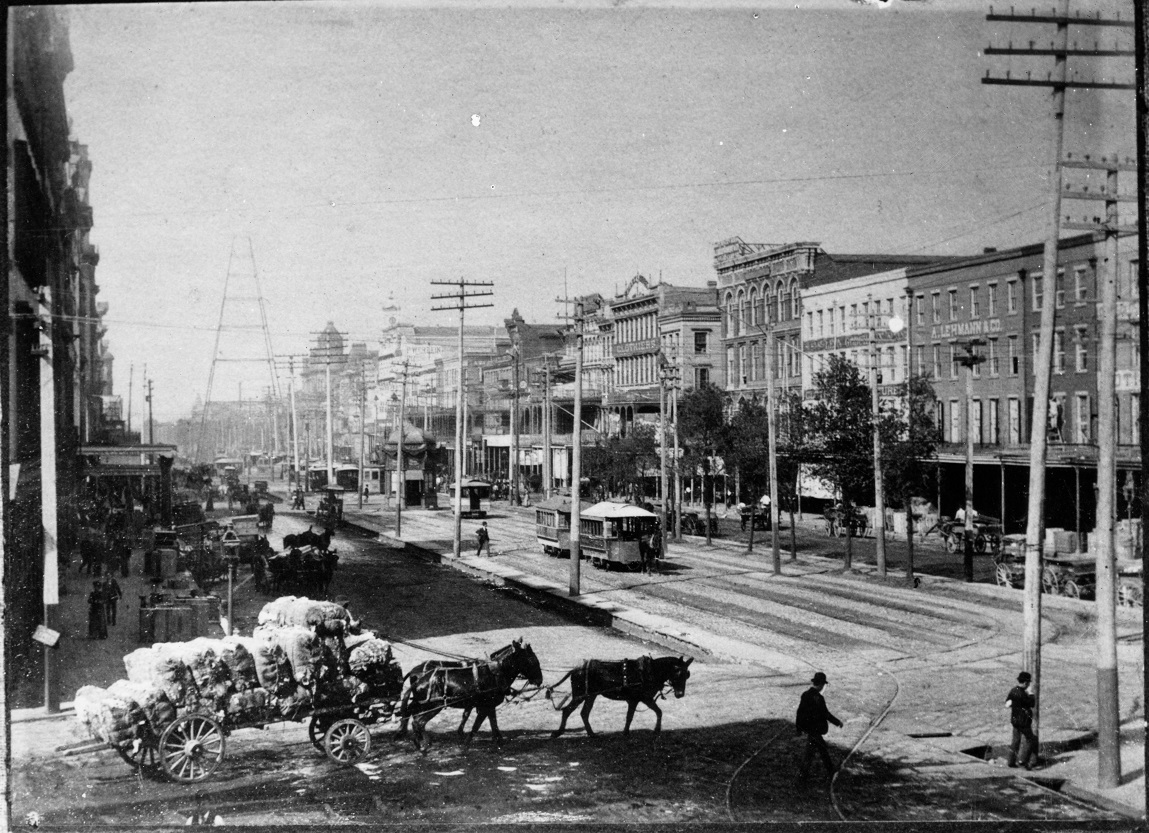

Charles L. Franck Collection, The Historic New Orleans Collection

Canal Street before 1892, with mules prominent.

An obvious question about the epizootic was “how do you pronounce it?” According to a note in the Picayune of November 30, 1872, the correct pronunciation was “epi-zoo-AH-tic,” not “epi-ZOO-tic.” The writer further advised that this was the adjective, and that the noun was epizooty, or “epi-zoo-AH-tee.” (The Oxford English Dictionary generally agrees with this.) The preferred term in the contemporary press was “epizootic,” which has become the most common modern term, with “epizooty” occasionally appearing.

The disease was a virulent influenza that affected horses and mules. It first appeared in Toronto, Ontario, in late summer of 1872, and quickly spread, via railroads, throughout Canada and the United States. The disease was not always fatal, but its toll can be counted not only in thousands of dead and weakened animals, but in the havoc it wreaked on American urban life.

In that day, no one could imagine a city without horses and mules. New Orleans’s streets echoed with hoof beats and reeked of dung. Cities depended on horses and mules to haul the wagons that carried goods, to bring the fruit and vegetable vendors and milk wagons to neighborhoods, to move passengers in carriages and streetcars, to carry riders in saddles or carriages or wagons to their destinations, to drag fire engines and ambulances, to pull plows and “honey wagons” collecting garbage and filth from cesspits, and drag the apparatuses that built and maintained the all-important river levees. Horse power in that time was not just a measurement; it was an actuality.

Besides their practical use, racing horses had long been a popular fall and winter sport in New Orleans. The Louisiana Jockey Club held their meets at the Fairgrounds Race Track, and felt there was “every promise of a most successful meeting” when they announced on November 28, 1872, that Saturday, November 30, would begin the fall racing season. That day the Picayune noted “there has not been the first symptom of the horse disease in any of the track’s stables.” The African American newspaper Weekly Louisianian also hailed the racing season’s start. Unfortunately, attendance was disappointing, and the Picayune on Monday blamed “the horse disease” for severely limiting transportation of fans to the track. On Saturday, December 14, $11,000 in purses were promised for a three-race card. The next day the Picayune noted that “there was room in the grand stand for a great many more people than were on hand.” The Jockey Club held races for the third and last time that season on Tuesday, December 17. “Attendance was exceedingly discouraging,” the Picayune explained.

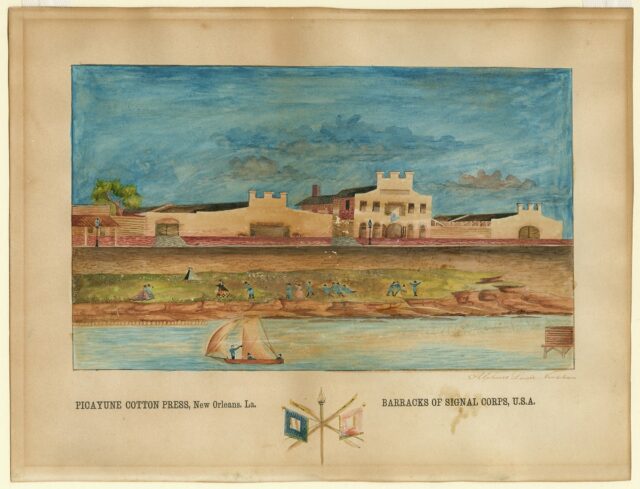

Cotton presses, like the Picayune Cotton Press shown in this watercolor painted by Louis Alphonse ca. 1862, relied on horse and mule power. The Historic New Orleans Collection

Under the headline “The Horse Plague,” the Picayune on December 4 listed effects on the city: merchants resorted to “all the ingenuity they can devise . . . several floats [flat cotton wagons still used in Carnival parades], drays and wagons may be seen drawn by oxen, and our reporter noticed two floats drawn by men harnessed to the vehicles.” Most horses were in “heavy blanket covers” and not off the sick list. As reported in the Daily Republican on December 6, when all the animals on the St. Charles streetcar line were sick, the employees themselves pulled the cars along a shortened route, from Napoleon Avenue to just past Tivoli (currently Lee) Circle and back. Firemen had to pull their own engines and held burial services for their faithful equine companions. Downtown office workers had to arrive on foot: one man resorted to being delivered via wheelbarrow, and a tugboat offered to bring uptown residents to the business district on the river. Braselman and Adams Dry Goods Store on Magazine at St. Andrew acquired eight ponies to make deliveries of ladies’ goods.

The Picayune on November 27 carried an advertisement for steam engines. “Horses and mules may get” the virus “but the traction steam engine does not,” noted Mr. H. E. Lawrence of Customhouse Street, who offered “two traction steam engines” for sale, assuring possible buyers that the engines “can travel on any road . . . haul one hundred bales of cotton . . . and be worked by one man.”

Even the artist Edgar Degas, who was visiting his New Orleans relatives for the entire time the epidemic raged here, was impressed by the use of steam engines for streetcars when he was shown the engines of local manufacturer Emile Lamm, which were eventually used on the St. Charles to Carrollton route. Cars on the Prytania and Magazine lines were also pulled by steam engines. (Lamm engines, with a system that used ammonia, would be used at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1878.)

The commercial life of the city had to continue. On November 29, in an advertisement headlined, “No delay in moving cotton, horse disease or no horse disease,” the Atlantic, Phoenix, Natchez, and Levee cotton presses advertised their hiring of the Harbor Tow Boat company to transport their cotton bales from their presses (warehouses where bales of cotton were compressed for shipping) to barges and ships.

In another solution for the cotton market, on November 29, the Picayune ran a notice that “arrangements were made to connect the Jackson Railroad with the Mobile and Texas Railroad, making a continuous line along the levee from Elysian Fields Avenue to the uptown cotton presses with switches to the river at two or three different locations.” Tracks were quickly laid for the purpose, and were dismantled when the emergency passed.

A railroad connection inside the area of the Port of New Orleans was begun as a solution to the lack of mules and horses. It would later be a major improvement to the port when, in 1904, the Public Belt Railroad Commission was created to set up and run the Public Belt Railroad, a switching system to transfer cars of all railroad companies to wharves and industries through the port. It still functions today.

The winter of 1872–1873 was a difficult time for New Orleans. Reconstruction was underway, with all the good effects it aimed to have: between 1870 and 1874 a portion of public schools were desegregated, and the franchise was extended to African American men. However, the white population was increasingly restive. The 1873 Carnival season was marked by the Comus parade “Missing Links,” featuring insulting caricatures of Reconstruction officials and prominent African Americans. In 1874 a pitched battle on Canal Street would be waged between Republican state government forces, including African Americans, and the Crescent City White League. A growing economic downturn added to the city’s woes. Degas’s 1873 painting A Cotton Office in New Orleans depicts his family’s firm as it is about to go out of business. Agriculture statewide, all-important to the city’s economy, suffered from the loss of mule power to haul sugar cane to the mill for grinding and the last of the cotton crop to the gin for seed removal.

But the outbreak, at least, would end in the United States within a year, making manifest the Picayune’s declaration, on December 27, 1872, that the pestilence “will soon be remembered only as a strange and unaccountable visitation, which for a time being had its sway and worked out its mission of disease and death.”

Carolyn Kolb is a native of New Orleans and the author of New Orleans Memories: One Writer’s City, a collection of essays she wrote for New Orleans magazine. She holds a doctorate in Urban Studies/ Urban History from the University of New Orleans.