In the Wind

A petroleum state explores wind power

Published: May 31, 2022

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

Photo by Zack Smith

West Cote Blanche Bay at Luke Landing in St. Mary Parish.

Orgeron, fifty-five, a Republican from Galliano, won outright in the primary for the District 54 seat, besting the other five candidates by wide margins. He ran, he told me recently, as a “pro-business, limited-government conservative.” One of his Facebook ads advocated against COVID restrictions. To the voters in this oil and gas stronghold, he touted his experience in the energy industry and received the endorsement of the Louisiana Oil and Gas Association’s political action wing. (Orgeron suspects name recognition also played a role in his win. He grew up “down the bayou,” in the local parlance, and is the fourth cousin of Ed Orgeron, the former Louisiana State University football coach.)

Orgeron’s family counts itself among the original Cajun mariners that helped develop the offshore oil and gas industry. In the 1960s, his father started a company called Montco that Orgeron and his brother would eventually take over, building boats essential to the offshore oil business, including some of the first liftboats—flat-bottomed, three-legged vessels with jacking systems deployed near oil platforms—for which the company would ultimately become best-known.

But over the past decade or so, Orgeron has charted a different path.

“I was Don Quixote for a while, chasing windmills,” Orgeron joked of his move into the wind energy sector. But “since Joe Biden won and you’re hearing about offshore wind on the news almost every day—renewables, the drive to net zero—fewer and fewer people are looking at me as being a turncoat and more prophetic, I guess.”

A pair of studies released in 2020 by the National Renewable Energy Laboratories, which indicate strong wind resources off the coast of Louisiana and suggest significant economic opportunity for states bordering the Gulf of Mexico, have caught the attention of everyone from Governor John Bel Edwards to economic development officials, who see in offshore wind a rare chance to tap existing skill and supply chains.

The LB Caitlin, one of the liftboats that carried turbines to the Block Island site, docked in Houma. Photo by Zack Smith.

“This could be described as a generational opportunity,” said Michael Hecht, president and CEO of the economic development group Greater New Orleans, Inc. “We are taking a state that has for past generations been dependent on the oil and gas industry and seeing that future generations might be able to apply similar skills and build similar middle-class families and opportunities by leveraging offshore wind.”

(Like most public officials I spoke with, Hecht is quick to temper his enthusiasm with a promise that Louisiana will continue to embrace oil and gas for the foreseeable future. “It’s not an either–or,” he said. “We think that there’s going to be a portfolio approach, with renewables increasingly part of the mix.”)

Orgeron got involved in the wind industry largely by accident, while on a work trip to the East Coast to explore new applications for his liftboats. He’d grown weary of the work to be found in the Gulf, where he said the bulk of his operations centered on decommissioning old, non-producing oil wells. “It had a dead-end-road type of feel to it,” Orgeron said. “Like a glorified undertaker. It didn’t sit well as a business model for me.”

Orgeron was in Atlantic City with one of the company’s liftboats for a scientific coring job when he said he started getting calls from wind companies investigating prospects for the nascent offshore wind industry taking shape on the Eastern Seaboard. Over the course of a day, he said, he got three calls from three different companies, all of them interested in using his vessel for ocean floor sampling to gauge the suitability of prospective wind farm sites. Ultimately, Orgeron’s was one of several Louisiana-based companies involved in Block Island, the nation’s first offshore windfarm, which came online off the coast of Rhode Island in 2016.

More than sixty years ago, the journalist A. J. Liebling wrote that Louisiana “swims on oil and gas like a drunkard on whiskey.” Some might argue that not much has changed in this respect. Louisiana’s sinking, shrinking coastline is blamed in significant part on decades of oil and gas extraction, while climate change—largely caused by the burning of fossil fuels and resulting in stronger, more frequent storms and rising sea levels—is only heightening the state’s vulnerability, as acknowledged by the state’s first climate action plan adopted earlier this year. Yet oil and gas remains a staple of the state’s economy and, maybe more importantly, its identity, even as jobs in the sector have declined over the past several years, a function of pandemic-related demand drop-off, changing technology, and political factors, among others.

Capt. Mark Lane and Rep. Joe Orgeron at Christie Industries in Houma. Photo by Zack Smith.

In a noteworthy signal that the state’s energy culture may be changing, some unlikely actors with strong ties to oil and gas, including Orgeron, find themselves on the frontlines of the energy shift they say is undeniably underway. Some are motivated by an environmental sensibility. For others, their interest is rooted in simple pragmatism, as well as the allure of being part of a burgeoning industry.

“I think we’re at a transition period in energy, and the guy that was making the leather horse saddle hopefully at some point started making leather seats for cars,” said Roy Francis, fifty-two, who in his former role as head of development and strategic planning for Gulf Island Fabrication—historically focused on building steel structures for the offshore oil and gas industry—pursued and oversaw the company’s first foray into offshore wind.

Inspired by the successful development of offshore wind energy in Europe, technological advances that were dramatically reducing the cost of harnessing wind, and global pressures to shift to renewable energy sources, Francis said his team spent years researching opportunities before landing on Block Island.

“If there were going to be steel structures put into the territorial waters of the United States and that’s what we did as a company, we wanted to pursue it,” he said. Gulf Island’s Houma-based fabrication operation built the steel foundations for Block Island, as well as the liftboat that helped install it.

“The question for Louisiana is, are we in the oil and gas business, or are we in the energy business?” …If we’re in the oil and gas business, that’s a declining industry. If we’re in the energy business, there’s no end to the possibilities.”

David Dismukes, director of Louisiana State University’s Center for Energy Studies, says public conceptions of the oil and gas industry in the state can be outmoded. “There’s this historic perception that oil and gas is anti-renewable, and that’s really not true,” he said, pointing to mega operators like Shell and BP that are investing heavily in wind and other renewable projects.

Lafayette-based businessman Harold Schoeffler says it’s time the state followed suit. “The question for Louisiana is, are we in the oil and gas business, or are we in the energy business?” said Schoeffler, who until about ten years ago made a living selling luxury vehicles to the oil and gas executives that were the backbone of his customer base at the eponymous Cadillac dealership he inherited from his father. “If we’re in the oil and gas business, that’s a declining industry. If we’re in the energy business, there’s no end to the possibilities.”

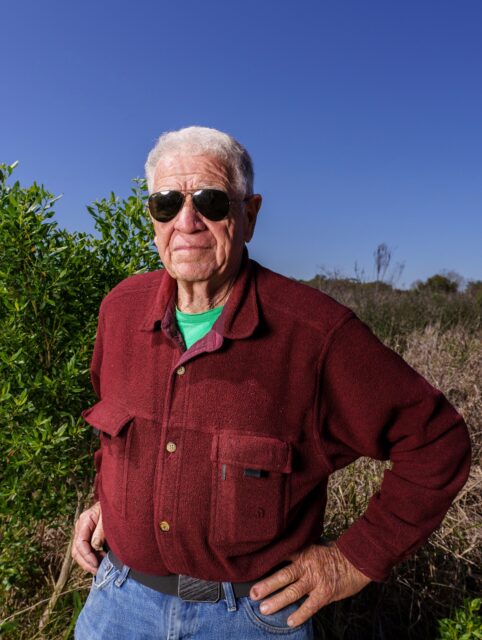

Schoeffler has been preaching the potential of wind energy for at least twenty years. In 2006, he and his business partner Herman Schellestede, a former oil rig engineer, were profiled by National Public Radio for their efforts to build the nation’s first offshore wind farm near Galveston. The project collapsed when financing fell short, but Schoeffler hasn’t given up. Now eighty-two, he thinks Louisiana is finally ready for the types of projects he’s long been pitching.

Schoeffler is currently pursuing a series of renewable-energy proposals he’s cooked up for the southern portion of the state. He’s soliciting investors on a hydroelectric power project in the Wax Lake Outlet in the Atchafalaya Basin and partnering on a thousand-acre solar farm that he says could power a quarter of Lafayette. And, although he didn’t get to claim the mantle of the nation’s first offshore wind farm, Schoeffler is working on proof of concept for what he estimates will ultimately be a $1 billion, three-hundred-megawatt wind project involving windmills mounted on concrete barges in Cote Blanche Bay that could be the first wind farm developed in state territory. (Although state waters don’t have the wind resources to be found further offshore, Schoeffler expects the disadvantages to be offset by lower transmission costs, better protection from hurricanes, and lower bureaucratic barriers to entry.)

“We hope this project goes,” Schoeffler said of the wind farm. “If it does, it’s a model. It produces revenue for the state, it produces jobs for the ports, and it lowers the cost of energy.” Schoeffler says the project could produce electricity for less than 4 cents per kilowatt hour, roughly half the average 2020 retail price of electricity in Louisiana.

Although all of his projects are still in the planning stage, Schoeffler has never been more optimistic about the regional appetite for renewable energy. “Perseverance is real important,” he told me. “And we ultimately will prevail, just out of necessity, the political climate, and public demand. Why is Tesla worth more than GM, Ford, and Chrysler combined in stock value? It’s the green future.”

What else has changed, Schoeffler added, “is that many of the enormous assets we have in Louisiana that support offshore oil and gas have become somewhat useless. Because the economics of the oil business have changed a lot.”

Harold Schoeffler hopes this patch of land will one day be a staging area for wind farm construction in Cote Blanche Bay. Photo by Zack Smith.

Whereas Schoeffler is the longtime chair of the local chapter of the Sierra Club, Orgeron rejects any environmental motivation behind his work. (“I’m a conservationist,” he said. “But I’ve told people openly, ‘I’m here with my green bucket so they can put money in it.’”) A physicist by training—he got his doctorate amid the 1980s oil bust that postponed his accession to the family business—Orgeron predicts oil and gas will remain South Louisiana’s “bread and butter” for the next decade, if not longer. He is in line with the governor in his belief that Louisiana is poised to become a leader in the renewable energy sector.

Orgeron and his brother are soliciting financial backers for a new venture: building a pair of proprietary vessels, dubbed “SuperFeeders,” that would ferry enormous wind farm components from the dock to their offshore locations for installation. Initially, these boats would be deployed on the East Coast, where the offshore wind industry is taking off, but Orgeron would like to bring them down to the Gulf Coast one day.

The name of their company is 2nd Wind Marine, a moniker Orgeron says refers to his personal experience in the offshore sector. But it could also serve as a fitting metaphor for Louisiana’s broader energy dilemma.

“There’s a second wind out there for all of us,” he said. “If net-zero carbon, non-hydrocarbon production continues, what else can we do? The needs of the offshore wind market are so parallel, for the most part, with oil and gas service industries that for a lot of people in our region—in the lower parishes of Louisiana, from Cameron all the way across to Venice and lower Lafourche—the talents that they have can definitely be parlayed into offshore wind.”

After leaving Gulf Island two years ago, Francis, who spent much of his professional life in Thibodaux but now lives outside of Houston, considered casting his lot with the wind industry. He did some consulting along those lines, but said he ultimately opted against a career centered on the East Coast, as it would mean too much time away from his family. Instead, he joined a business that bills itself as the oldest distributor of Shell products in Louisiana. Francis looks forward to exploring new opportunities for that company amid the energy transition.

A little less than two months after Hurricane Ida—one of the strongest storms ever to hit Louisiana’s coast—thrashed onshore near Port Fourchon, I found myself standing on the rocky beach along Block Island, Rhode Island, on an unseasonably mild late October morning. Looking out over the vast expanse of the Atlantic Ocean at the five wind turbines that appeared like silent sentinels on the horizon—their existence possible thanks to Louisiana-based expertise—I thought about a conversation I’d had with a woman on the main commercial strip in town. She was visiting the island with her husband for his seventy-ninth birthday. I asked her what it felt like, seeing the nation’s first offshore wind farm. She replied, “It feels like hope.”

Emilie Bahr is a writer, urban planner, Francophile, and mother to young children who lives in New Orleans. Her book Urban Revolutions: A Woman’s Guide to Two-wheeled Transportation, was published in 2016. She can be reached at [email protected].