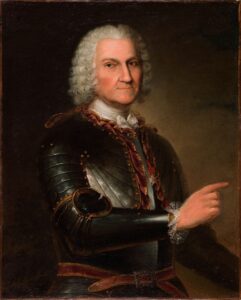

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, sieur de Bienville

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, sieur de Bienville, served as governor of Louisiana and founded the city of New Orleans.

This entry is 6th Grade level View Full Entry

The Historic New Orleans Collection

Portrait of Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, sieur de Bienville

What was Bienville’s early life and career like?

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, sieur de Bienville, was born February 23, 1680, in the frontier village of Montreal, Canada, to Charles and Catherine Le Moyne. He went to school at a Catholic seminary in Montreal before entering the French navy as a midshipman at the age of twelve. In 1696 he served with his brother Pierre Le Moyne, sieur d’Iberville, in Newfoundland, where he fought for the expulsion of English fishermen, and in Hudson Bay, where he was wounded during a battle to recapture Port Hudson in 1697. Afterward, at the age of eighteen, Bienville returned to France with Iberville and prepared for a 1698 expedition to Louisiana.

From 1699 to 1702 Bienville assisted Iberville in establishing a permanent French settlement in Louisiana. He played a key role in identifying Mobile Bay and the mouth of the Mississippi River. During this time he showed an exceptional ability to learn Native languages and negotiate with local groups, including the Bayogoula and Houma Indians. In 1700 Iberville made Bienville second in command of Fort Maurepas near present-day Ocean Springs, Mississippi. When Iberville returned temporarily to France, Bienville conducted several expeditions through the rivers, bayous, and lakes in the Lower Mississippi Valley. On one such expedition Bienville famously convinced the captain of an English ship to cease his descent down the Mississippi River at a point later called “English Turn.”

How did Bienville’s leadership affect the development of colonial Louisiana?

Bienville assumed the command of Fort Maurepas when the commander of the post died in 1701. Upon Iberville’s final return to Louisiana in 1702, Bienville was appointed governor of the colony and ordered to lead the construction of a post on Dauphin Island off the coast of present-day Alabama. During his first stint as governor of Louisiana from 1702 to 1713, Bienville struggled to manage military and commercial alliances with Native groups around Mobile, several of which were in contact with English traders from the Carolinas. Chickasaw and Choctaw Indians, the two largest and most powerful nations in the region, proved especially important to Bienville’s plans for the colony. It was during this time that Bienville organized annual gift-giving ceremonies with local chiefs in Mobile and followed lex talionis, or the law of retaliation (sometimes simplified as a policy of an “eye for an eye”).

Bienville gained a reputation for fighting with Roman Catholic clergy, misspending royal funds, and having affairs with French women in the colony. The French Minister of the Marine, Jérôme Phélypeaux, comte de Pontchartrain, responded to Bienville’s behavior by appointing Nicolas Daneau de Muy as the new colonial governor in 1707 with the authority to investigate accusations against Bienville. De Muy died before arriving in Louisiana, and Bienville was never found guilty, so he remained governor until sieur Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac arrived as his replacement in 1713.

Cadillac became governor at the same time the French crown gave control of the colony to Antoine Crozat. Though not governor, Bienville kept influence over the colony’s Indian affairs, especially after Cadillac insulted the Natchez and started an armed conflict. The establishment of Fort Rosalie on the Mississippi River in present-day Natchez, Mississippi, was the result of Bienville’s diplomatic efforts with the Natchez. In 1717, after only five years, Crozat suddenly gave up his fifteen-year monopoly. The French crown transferred control of Louisiana again, this time to the Company of the West led by the financier John Law. A year later Bienville was appointed commandant general, effectively making him governor of the colony again.

One of Bienville’s first duties as commandant was to establish a town thirty leagues up the Mississippi River and name it after France’s Duc d’Orléans, or Duke of Orléans. In 1718 Bienville chose a site on the east bank of the river where there was a “fine crescent,” though it was not until 1722 that New Orleans became the capital of the colony. He received two tracts of land around New Orleans, which were cleared and worked by some of the first enslaved Africans in Louisiana. In 1720 John Law’s financial scheme collapsed in France, leaving the future of Louisiana in question.

In 1725 Bienville came under investigation for financial misdeeds and was recalled to France. Étienne de Périer replaced Bienville as governor of Louisiana in 1725. However, after the 1729 Natchez Revolt, French officials summoned Bienville back to Louisiana. He immediately set out to repair relations with Native groups of the Lower Mississippi Valley. The Choctaws were especially important to Bienville’s plan to limit the influence of the Chickasaws and their English allies in Louisiana. He ordered four expeditions against the Chickasaws (in 1733, 1736, 1740, and 1742), all of which resulted in a combination of military and diplomatic failure. Bienville submitted his letter of resignation to the Minister of Marine in 1742. A year later, the Marquis Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil de Cavagnial arrived in New Orleans to replace the man who had resided in Louisiana for thirty-six years. Bienville spent the rest of his life in Paris, where he died on March 7, 1767.