French Colonial Louisiana

The era of French control over Louisiana was marked by many challenges, including hurricanes and conflicts with Native American groups like the Natchez.

This entry is 6th Grade level View Full Entry

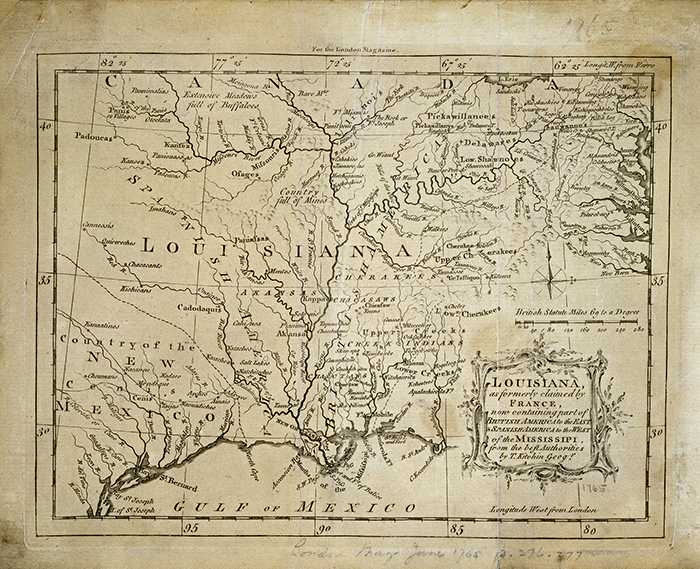

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection.

This map, dated 1765, shows the Louisiana Territory as claimed by France.

When and how did the first French settlements in Louisiana begin?

The French colonial period in Louisiana refers to the first century of permanent European settlement in the Lower Mississippi Valley. It lasted primarily from 1682, when René Robert Cavelier, sieur de la Salle, claimed Louisiana in the name of King Louis XIV in 1682, until 1763, when France turned over control of the colony to Spain following the Treaty of Fontainebleau and the Treaty of Paris. During this period Native Americans, Europeans, and Africans contributed to the development of a complex frontier society at the center of the Americas.

After La Salle’s failed 1684 effort to establish a permanent settlement in Louisiana, fifteen years passed before France sent another expedition. This time, a French minister named Louis Phélypeaux, comte de Pontchartrain, secretly made plans to establish French posts in Louisiana. He hoped that by establishing posts the French could undermine the interests of the English and Spanish along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. In 1699 Pierre Le Moyne, sieur d’Iberville sailed across the Atlantic and landed near present-day Biloxi, Mississippi, where he established Fort Maurepas. Iberville and his crew spent the next year exploring the Mississippi and Red River Valleys and made contact with the Natchez and other Native peoples. In 1702 Iberville moved the colony’s base of operations—along with roughly 140 French-speaking colonists—from Fort Maurepas to Mobile, where he hoped to develop closer trade and military ties with the Choctaws and Chickasaws to stop British expansion. Before leaving Louisiana later that year, Iberville gave considerable authority to his younger brother Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, sieur de Bienville.

The French Crown paid little attention to the needs of Louisiana or its inhabitants during the early 1700s, because it was involved in costly wars in Europe. Lacking official support, Iberville and his associates were unable to extract natural resources (furs, minerals, cash crops) from colonial territory. Supplies from France were extremely limited. To compensate for supply shortages, French colonists traded with neighboring Native tribes and relied heavily on their agricultural knowledge and enslaved labor in establishing early settlements.

To protect against the slave raids and military advances of British-allied tribes such as the Creek, Native people residing near Mobile developed close working relationships with the French. The Choctaws and Chickasaws were especially influential in how the French developed strategies to defend against the British and their Native allies throughout frontier areas east of the Mississippi River.

A 1708 census recorded 359 individuals in Mobile, including 60 Canadian fur traders; 122 soldiers, sailors, and craftsmen employed by the Crown; 80 enslaved Native people; and 77 other European men, women, and children. A handful of Catholic missionary priests traveled through or settled in the colony, though they had limited success converting Native people or gaining support from the French laity.

How did Antoine Crozat and John Law affect the development of early colonial Louisiana?

Iberville’s younger brother Bienville became acting governor in 1711. The next year Antoine Crozat, councilor and financial secretary to King Louis XIV, received a fifteen-year commercial monopoly over Louisiana. Louis Juchereau de St. Denis conducted an expedition up the Red River, resulting in the establishment of a French post at Natchitoches in 1714. Two years later the French established Fort Rosalie in present-day Natchez, Mississippi. The European population of Louisiana increased from approximately 200 to 500 inhabitants during the Crozat years (1713–1717). Fur trading remained the primary source of income for the colony. There were also rather unsuccessful attempts, first, to trade with Spanish and French colonies in the Caribbean, and second, to grow and harvest silk, indigo, and other cash crops.

Crozat pulled out of his commercial contract in 1717. The Scotsman John Law then assumed control over all trade in Louisiana, including the African slave trade, through an organization called the Company of the West. Law obtained the company charter as part of a larger plan to improve French finances by shifting French currency from gold and silver to paper money, reducing the Crown’s debt, and improving its credit. The plan, which was also intended to bring wealth to Law and his business associates, ultimately failed in 1720, causing a financial crash that impacted both France and Louisiana.

Despite the Company of the West’s failures, it was soon reorganized as the Company of the Indies, and it continued to operate in Louisiana until 1731. The companies’ investment in Louisiana brought considerable changes in the organization and makeup of the colony. Bienville established New Orleans in 1718 on a site long used by Native people as a trading ground. In 1722 New Orleans became Louisiana’s capital. That same year the site was struck by a devastating hurricane. After the storm, forced laborers cleared the site and engineers established the street grid that still exists as today’s French Quarter.

Outside New Orleans the company granted land to colonists along the Mississippi River, including in the area known as the German Coast. Located in present-day St. John the Baptist and St. Charles Parishes, the German Coast was, by 1722, home to roughly 300 German-speaking settlers, many of whom had arrived as indentured servants attracted to Louisiana by John Law’s Company of the West.

Settlers smuggled trade goods throughout the Mississippi Valley and the Caribbean to avoid the mercantilist laws of the companies and later the French Crown. The growing white population included peasants, craftsmen, farmers, and indentured servants; Catholic clergy and a contingent of Ursuline nuns; wealthy investors; criminals forced into exile in Louisiana; military officers, Swiss mercenaries, and poorly trained soldiers; and women exiled from Parisian hospitals and asylums, among others. Their arrival ultimately raised the European population to around 5,000 by 1721. However, that number dropped to fewer than 2,000 by the end of the 1720s due largely to high death rates and the decision by many to abandon the colony.

How did slavery contribute to the development of French colonial Louisiana?

The forced migration of approximately 6,000 enslaved Africans constituted the most significant demographic change to French colonial Louisiana during the 1720s. Approximately two-thirds of the enslaved men, women, and children were brought on company-owned slave ships from the Senegambian region of West Africa, while the rest came from Angola and the Bay of Benin. Enslaved people brought with them knowledge of rice, tobacco, cotton, and indigo cultivation, as well as an assortment of technologies and skills related to craftsmanship, all of which were considered useful for the development of a fledgling colony in the Americas. Enslaved Africans and Indians interacted on a daily and intimate basis, effectively undermining the intention of French slaveholders to control the thoughts and actions of their human property. In 1724 French officials implemented the Code Noir, or Black Code, in hopes of controlling the everyday lives of enslaved and free people of African descent in Louisiana, much as the French government had done in other French colonies throughout the Caribbean. Such efforts produced mixed results, with some enslaved Africans taking advantage of Louisiana’s frontier conditions by running away and establishing maroon communities (le marronage) in cypress swamps throughout the Lower Mississippi Valley.

By 1732 enslaved Africans accounted for approximately 65 percent of the total population of Louisiana. The majority of enslaved Africans lived and worked on private plantations along the Mississippi River away from New Orleans. Near the capital, however, many enslaved Africans worked on plantations owned by the governor, the Catholic Church, the Company of the Indies, and later the king. These enslaved men, women, and children made up 12 percent of New Orleans’s population in 1726. People of African descent born in the colony, or Afro-Creoles, would make up more than 50 percent of the total population of Louisiana by the end of the French colonial period.

How did economic and military difficulties effect the development of the colony?

On the morning of November 28, 1729, Natchez warriors killed more than 200 French men, women, and children, and captured between 50 and 150 enslaved Africans and 54 French women and children, holding them hostage. The attack took place after the French military commander at Fort Rosalie ordered the Natchez to turn over one of their villages for his own personal use. Approximately 10 percent of Louisiana’s white population died in the attack. The French government responded to the Natchez uprising by reclaiming Crown authority over Louisiana in 1731. Under the leadership of Bienville and with the assistance of the Illinois, Tunicas, Choctaws, and other Native groups, French soldiers spent the next decade conducting a series of military campaigns against the Natchez and Chickasaws, who had allowed some of the Natchez to take refuge with them.

Military expeditions against the Natchez and Chickasaws produced mixed results. French forces recovered many of the European and African captives. Many of the girl children orphaned in the attack were sent to live with the Ursuline nuns in New Orleans. The French and their allies also killed and captured many Natchez and sent nearly 300 captives into slavery in the French Caribbean. At the same time, the French failed to achieve any clear victories over the Chickasaws, and their alliance with the Choctaws was weakened. French officials continued their attempts to improve Louisiana’s economy by encouraging tobacco cultivation and trade, again with only modest success. Currency inflation and poor weather, including a devastating hurricane, did not make their jobs any easier. Much of the blame for the colony’s decline fell upon Bienville, who was finally replaced as governor in 1742 by the Marquis Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil de Cavagnial.

By 1746 the population of French colonial Louisiana had shrunk to approximately 3,200 whites and 4,730 African-descended people, due primarily to the return of many settlers to France, the low number of new European immigrants, high mortality rates, and the near-complete stop to the importation of enslaved Africans.

With the governorship of Vaudreuil came a new level of prosperity in Louisiana. From 1744 to 1755 trade and the colony’s population increased, despite French involvement in multiple wars. Some large plantation owners along the Mississippi River replaced tobacco with the more profitable indigo, though small-scale farming of other cash crops and lumbering continued. The increase in plantation productivity also marked an increase in the importation of enslaved Africans, most of whom came from the French West Indies. Some historians estimate that the population increased by as much as 50 percent this period. Most European colonists lived near New Orleans, Mobile, or Natchez.

Disputes among the Choctaws, Chickasaws, French, and English increased during the 1740s and 1750s. Red Shoe, a Choctaw chief, encouraged parts of the Choctaw nation and the Alabamas to trade with the English. Vaudreuil, in an attempt to undermine Red Shoe, organized a diplomatic ceremony for around 1,200 Choctaws to meet with French officials in 1746. Tensions reached a high point when Red Shoe killed three French traders and Vaudreuil called for revenge. A Choctaw warrior ultimately assassinated Red Shoe. By 1747 the Choctaws were at war with each other, as villages drew battle lines according to English or French alliances. It was not until the French provided their Choctaw allies with sufficient supplies that peace was restored in 1750. However, major military conflict between the French and Chickasaw resumed in 1752, when Vaudreuil ordered attacks on Chickasaw villages in present-day northern Alabama and Mississippi. The Chickasaw effectively fought off the French with the help of the English.

How did France lose control of Louisiana?

Governor Louis Billouart, Chevalier de Kerlerec, arrived in New Orleans in 1753. French-Indian relations and the Seven Years’ War (French and Indian War) were the most important issues facing the colony. The deplorable state of Louisiana’s forts and military convinced Kerlerec that he would need the assistance of the Native population if he wanted to protect the imperial interests of the French against the English.

After several years of diplomatic negotiations, the French convinced the Spanish to ally themselves against British interests in Europe and the Americas. The secret signing of the 1762 Treaty of Fontainebleau involved France’s King Louis XV promising Spain’s King Charles III the territory of Louisiana and the so-called Isle of Orleans (New Orleans). However, the 1763 Treaty of Paris, which ended the Seven Years’ War, granted territories west of the Mississippi River, including the Mobile settlement, to the English.

It is not entirely clear why Louis XV so willingly gave Louisiana to Spain. Most historians cite Louis XV’s interest in strengthening Franco-Spanish ties and giving up control over a burdensome colony. Regardless, the decision to cede Louisiana to Spain had little short-term impact on the local population.