From Freeman and Harris to Orlandeaux’s

A Shreveport family upholds more than a culinary legacy

Published: May 31, 2023

Last Updated: August 31, 2023

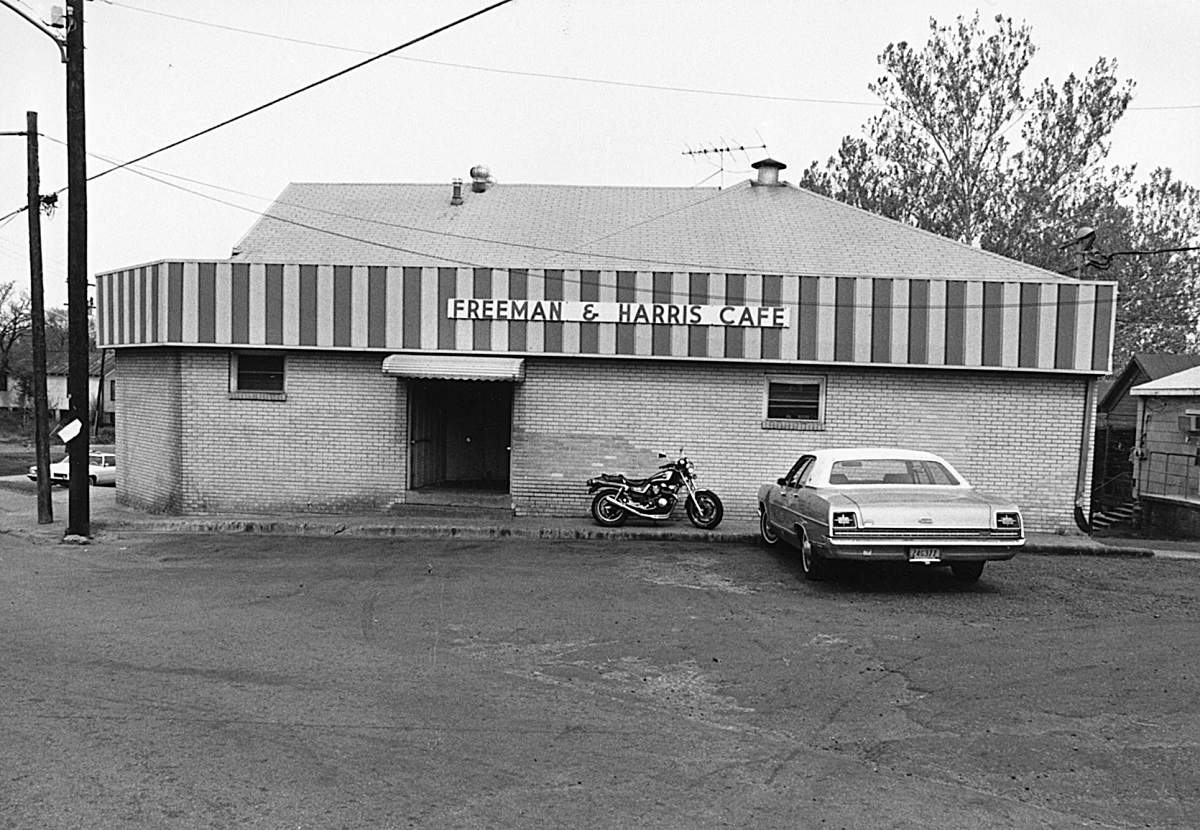

Photo by Neil Johnson, Northwest Louisiana Archives, LSU Shreveport

Freeman and Harris Cafe, 1984.

When I first met owner Damien “Chapeaux” Chapman, I was midway through a deeply comforting bowl of divinely seasoned seafood gumbo. After finishing my final spoonful, I looked out at Cross Lake, which is the primary water supply for the city of Shreveport. Damien followed my gaze. He noted, “We are the city’s main and longest source of good food, and we sit out on the city’s main source of water. There’s something powerful about that.”

Indeed there is. Since establishing the eatery in 1921, Chapman’s family has owned and operated various iterations and locations of Orlandeaux’s Café, a culinary institution and living demonstration of Shreveport’s Black gastronomic history by any name. Some know it as Freeman & Harris, some Pete Harris Café; at one point it was called Orlando’s, in honor of Chapman’s father and the restaurant’s fourth-generation owner, Orlando Chapman Sr. Damien opened Orlandeaux’s—the latest incarnation, with a “French twist” on the name—in 2021, in the old location for Smith’s Cross Lake Inn, which had been a white-owned restaurant and inn.

“We’ve been carrying these same recipes for a hundred years—passing down five generations,” Damien said. “We’ve moved here, and we’re the first Black business to be held in these walls. It’s pretty remarkable—and amazing to show where we’ve come and how far we’ve come.”

Damien’s great-great-great uncles, Jack Harris and Van Freeman, founded the storied restaurant. Natives of the Campti area of Natchitoches Parish, the two moved to Shreveport between 1918 and 1920, and started Freeman & Harris on Texas Avenue, less than five miles from the current location. The restaurant moved and was eventually renamed to Pete Harris Café in tribute to Damien’s grandfather’s cousin, Pete Harris, one of many family members who helped run the place during the twentieth century. It was the most well-known version of the restaurant, according to Damien. When Damien’s grandfather, Willie “Brother” Chapman, passed away, Damien’s father Orlando Chapman took ownership, naming the restaurant Brother’s Seafood in honor of his own father, who went by the nickname “Brother.” Orlando opened multiple locations around the city, and this era of the restaurant changed Damien’s life.

“Just like past generations, I was born into this legacy,” he said. His childhood memories are punctuated by working at the café with his father and grandfather. He met people who would remain committed to the restaurant, like manager Patricia Jones, who runs the restaurant’s tartar sauce production and has worked with the Chapman family for generations. He recalled sitting on a stool to help with to-go orders, rolling silverware and separating salt and pepper shakers, taking on any and everything to learn the business. “I worked there all throughout high school. I was a busboy, a dishwasher, served tables, and then managed to work my way into the kitchen.”

After finishing his undergraduate studies at Southern University in Baton Rouge, he found work in Lafayette’s oil and gas industry. But when his father passed away unexpectedly from a heart attack in 2013 while boating on the same lake on which Orlandeaux’s now sits, Damien pivoted.

“I had to drop everything to come home and to pick up the pieces,” he said. “Managing a restaurant and running around as a teenager is one thing, but owning an almost-one-hundred-year-old business is a completely different thing.”

“We are the city’s main and longest source of good food, and we sit out on the city’s main source of water. There’s something powerful about that.”

For Damien there was never a question about whether or not the restaurant would be sustained—its storied history mandated its endurance. In 1958 a young Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at Galilee Baptist Church—a nine-minute drive from Orlandeaux’s—to encourage voter registration. When the restaurant was at Lawrence and Travis (now Pete Harris Drive), it stood in St. Paul’s Bottoms, a bright spot in a red-light district with a deeply complex and layered history. B. B. King and Bobby Blue Bland were among many Black musicians who dined at the café, and the restaurant played host to local and state politicians like former governor Edwin Edwards. As schools integrated in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Willie “Brother” Chapman (Damien’s grandfather) continued preparing dishes like crawfish étouffée and catfish Campti—fried catfish smothered in crawfish étouffée over a bed of rice—at Freeman & Harris Café near the edge of St. Paul’s Bottoms—and eventually at Pete Harris Café on Milam Street. The city of Shreveport evolved, shifted, and re-emerged into new possibilities, much like the restaurant that’s called it home for more than one hundred years.

“I realized, ‘All your ancestors before you had given up their lives to make sure the business continues, and you must do the same thing,’” Chapman said. “I was like, ‘I cannot let this die on my watch.’”

Even in the face of challenges—including shuttered doors and financial setbacks—the restaurant has successfully reinvented itself yet again, without losing its original charm. For Damien, maintaining the restaurant’s presence in the city is part of continuing its role in the city’s rich Black history. The food has drawn guests to the restaurant for centuries, but its role as a safe space in a daunting time of racism and segregation is what made it a Shreveport institution.

“During segregation, Blacks and whites felt really comfortable dining at our restaurant,” Damien said. “That was the only place in town where Blacks and whites really went to. They didn’t go to church together, they didn’t work together, they didn’t go to school together. But they were very comfortable eating our food, in the same building, in the same room, at the same tables with each other without fear of being attacked or being judged.”

The food at Orlandeaux’s remains tethered to the city’s enduring gastronomic landscape. New Orleans maintains its place as a flashy centerpiece of Louisiana’s culinary identity, but cities like Shreveport are where the state’s cuisines get their fundamentals, defined by humble origins and prepared by people who value cooking that’s slow, substantial, and rooted in equal parts flavor and depth.

At Orlandeaux’s, Damien said, “you see things that you don’t see in other restaurants. Smothered beef liver, fried gizzards, and smothered chicken liver—stuff that brings you home.”

At the lakeside restaurant, picturesque views envelope the impressively sprawling building. A gregarious bartender named Brandon served up daiquiris as customers placed orders for restaurant specials like oyster and sausage po-boys and fried chicken sandwiches. And of course, there’s stuffed everything. Seafood and vegetables—think crab and bell pepper—are all fair game for stuffing opportunities. And, in lieu of the more common fillings of cream cheese and boudin, Damien does stuffed shrimp Shreveport style: he splits the shrimp open, adds a generous heap of crab meat stuffing touched with a bit of heat, and deep fries the seafood, producing an oblong shape.

“It doesn’t look like a shrimp at all and kind of looks like a mini corn dog,” Chapman said jovially. “Most people, when they see it, say, ‘Holy crap, what is it?!’”

Damien carries great pride in the restaurant’s role as a welcoming place for all people, serving universally appreciated local cuisine. But it must be said that Blackness is the root of Orlandeaux’s intrigue and success. Guests eat their flaky, expertly battered crawfish to a backdrop of zydeco music and classic R&B tracks like Ray Charles’s “Unchain My Heart,” creating the kind of comforting atmosphere that’s pervasive in many of the most historic Black restaurants throughout the South. Here, good food and service has created an enduring pathway for the Chapman family, one that Damien hopes to extend well into the decades ahead.

“People remember that this is a thing of their fond memories—a place that they grew up on and that their grandmothers talked about. To still be able to have this around means a lot to the entire community, Black and white.”

At Orlandeaux’s, extending that comfort to the community always starts on the plate.

Kayla Stewart is a food and travel writer from Houston, Texas. Her work has been featured in the Southern Foodways Alliance, New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, Travel + Leisure, Condé Nast Traveler, Texas Monthly, and others.