Saints, Tribes, and Kings

The origins of Louisiana parish names

Published: February 28, 2022

Last Updated: May 31, 2022

Photo by Billy Hathorn

Interpreting toponyms has its limits. Official place names are prone to the powerful, and sometimes reflect only the whim and worldview of the few. To wit, note the relative paucity of African toponyms on the southern landscape, despite high numbers of people of African descent. Other toponyms tend to be capricious or generic, though those too can have subtle meaning.

Louisiana’s place names are rich in cultural content, and no better way to see how than by examining our sixty-four parishes. (The term parish itself, of course, reflects Louisiana’s historical status as one of the most Catholic states in the union, while the toponym Louisiana is about as French as one can get, named for King Louis XIV—the only American state named for a French king).

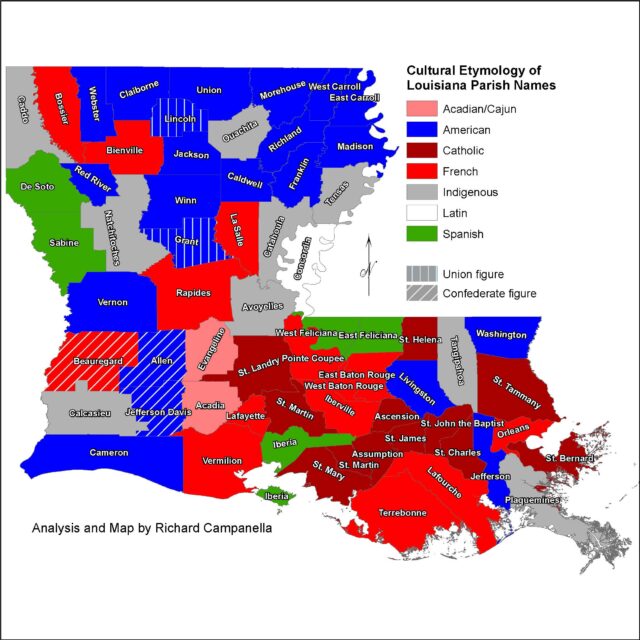

One might think that Francophone references might predominate among our parishes. They do if we consider Gallic influence broadly, and aggregate French along with Acadian names plus the Catholic saints and feasts associated with those populations. About 20 percent (13 of 64) of our parishes have purely French names, seven of them for people (Bienville, Beauregard, Bossier, Iberville, Lafayette, La Salle, and Orleans, the last inferring Phillipe II, the Duke of Orleans) and the rest for geographical features. “Lafourche” meant the bayou of the same name as it forked off from the Mississippi; “Pointe Coupee” came from a river meander; “Rapides” implied the seasonal waterfalls (rapids) in the Red River at Alexandria; “Terrebonne” means good earth; “Vermilion” derived from an old French word meaning red, as in the ruddy color of the Vermilion River, and East and West Baton Rouge Parishes got their names from the red pole used to demarcate the hunting grounds of the Ouma (Houma) and Bayogoula tribes, first documented by Iberville in 1699.

Another two parishes, Acadia and Evangeline, might be considered more French Canadian, Acadian, or Cajun. Relatedly, there are ten parishes whose names come from the lexicon of Catholicism, among them two feasts (Ascension and Assumption), and eight patron saints: St. Bernard, St. Charles, St. Helena, St. James, St. John the Baptist, St. Landry, St. Martin, St. Mary, and St. Tammany, the last of these a fusion of hagiography with a reference to the Delaware Valley indigenous chief Tamanend, known as “Patron Saint of America.”

So while pure French references comprise 20 percent of our parish names, the larger Franco-Acadian-Catholic cultural tally is 41 percent, or 26 of our 64 parishes.

The next-largest cohort comprises those parish names of Anglo-American reference, which make up 34 percent, or 22 out of 64 parishes. Most invoke American presidents (Washington, Jefferson, Jackson); governors or statesmen (Claiborne, Webster, Franklin); or prominent locals (Caldwell, Morehouse, Winn), while two connote geographical features (Red River and Richland, the latter coined for the area’s rich alluvial soils). Union Parish was an antebellum affirmation of the federal union, as were Lincoln and Grant for the postbellum era, while some say Vernon Parish got its name from George Washington’s home of Mount Vernon.

Indigenous terms make up 14 percent (9 of 64) of Louisiana parish names: Avoyelles, Caddo, Calcasieu, Catahoula, Natchitoches, Ouachita, Plaquemines, Tangipahoa, and Tensas. Six were names of tribes or chiefs, and three connoted local features or flora.

Spanish references make up 8 percent (5 of 64) of our parish names, although that number would increase if we attributed some of those Catholic names to the Spanish as well as the French influence in Louisiana. Perhaps the most culturally meaningful is Iberia Parish, where Spaniards from Málaga settled as part of an attempt of Spanish colonial administrators to Hispanicize the otherwise francophone colony of Luisiana. Then there is Sabine, along the former border with Mexico (now Texas), which comes from the Spanish word for the cypress tree. DeSoto Parish is named for Joseph Marcel DeSoto, who established the Bayou Pierre settlement during the Spanish colonial period, and East and West Feliciana are said to be named for the wife of Spanish Governor Galvez at a time when that area became Spanish West Florida.

One parish name comes from Latin—Concordia, meaning harmony—and perhaps ought to be tallied with the American names, since it came courtesy of Anglo-Saxon migrants.

When we consider our parish nomenclature in toto, we see broad arcs of state history and culture. Louisiana’s Catholic population measures somewhere between 25 and 30 percent of the total population, not too far off from the proportion of Catholic parish names, which is 17 percent. Most Catholics live in the southern half of the state, as does every one of the Catholic-named parishes. Both Acadian-named parishes are in the heart of Acadiana, and while one can find any category of name anywhere, American names tend to predominate in the Anglo-Baptist north, above the so-called “boudin curtain,” while the Franco-Hispanic Catholic names dominate the southern half of the state map.

The number of parishes with more purely colonialist nomenclature number 5 for the French (La Salle, Iberville, Bienville, Orleans) and 4 for the Spanish (DeSoto, Iberia, and the two Felicianas). Compared to the 19 American names that directly reference political figures or ideals of the United States, that composition roughly matches the time periods which Louisiana spent under French and Spanish colonial control (the long eighteenth century), versus American dominion (the subsequent two centuries).

American names tend to predominate in the Anglo-Baptist north, above the so-called “boudin curtain,” while the Franco-Hispanic Catholic names dominate the southern half of the state map.

Two parishes bear pro-Union names, Grant and Lincoln. Both in the northern half of the state, their designation came during the Reconstruction period, backed by a biracial Republican state government. (Union Parish’s name may sound like it came from the same era, but in fact dates to 1839). Three parish names herald Confederate figures, and all three date from the so-called “Redemption” era following Reconstruction, when white supremacists regained political control and made an explicit point of valorizing the “Lost Cause.” Those parishes are named for General P. G. T. Beauregard, President Jefferson Davis, and General Henry Watkins Allen, who also briefly served as a Confederate governor. These three parishes abut each other, in the southwestern corner of Louisiana, far from the two Reconstruction parish names in the north. It’s as if the Blue and Gray are still glaring at each other across our map.

While African Americans had a say in the naming of Lincoln and Grant, there are zero parishes, historically or today, that allude to the cultural legacy of African Americans, despite that they make up 32 percent of the state population.

Native American allusions, on the other hand, make up 14 percent of the map of parish names, a figure which is approximately ten times greater than Native Americans’ modern-day share of the state population. One cannot help but note this demographic once constituted the entire regional population.

Toponyms reveal only the rough contours of our cultural history and geography. But they are nonetheless telling, particularly official ones like parish names, because they exude intentionality, bear gravitas, and inscribe their way into the Louisiana vernacular.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of The West Bank of Greater New Orleans, Cityscapes of New Orleans, Bienville’s Dilemma, and other books. He may be reached through richcampanella.com, [email protected], or @nolacampanella on Twitter.

Correction: An earlier version of this article erroneously stated that DeSoto Parish was named for Spanish explorer Hernando De Soto.