Louis Prima and the Sicilian Sound

The influence of Italian immigration on jazz and swing

Published: May 31, 2023

Last Updated: August 31, 2023

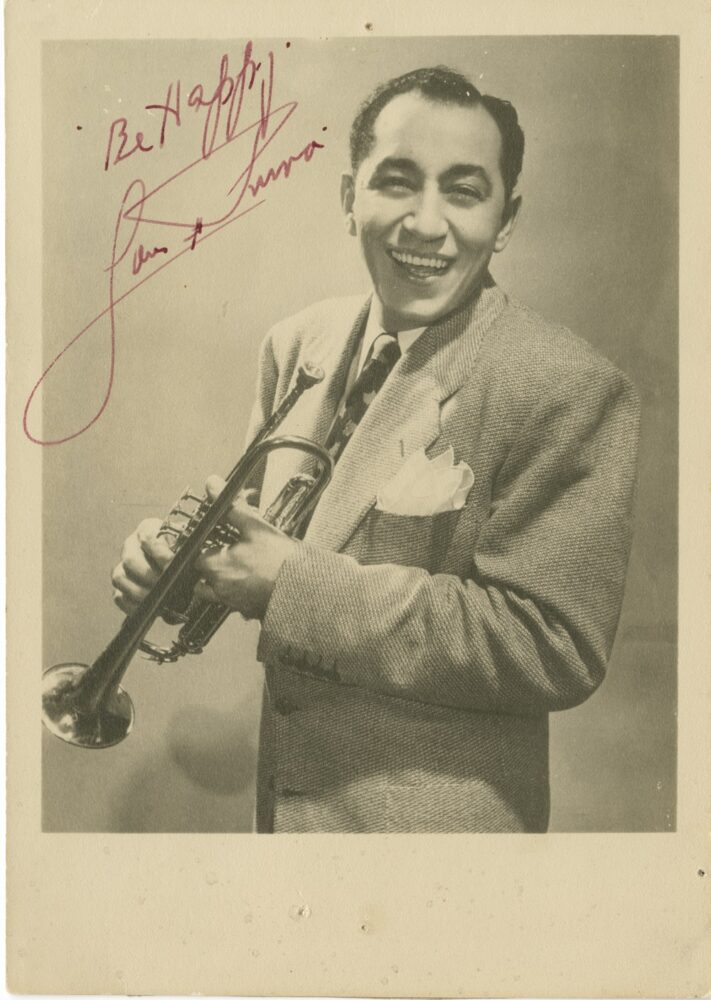

Hogan Jazz Archive, Special Collections, Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, Tulane University

Publicity photograph of Louis Prima holding trumpet, inscribed “Be Happy.”

At night after performances Guy Lombardo would walk the streets of New Orleans reveling in the fresh new music pouring out of the local honkytonks. One evening, on Bourbon Street, he heard a sound he described as “different and more piercing than any I had experienced.” He followed it in to 229 Bourbon, Leon Prima’s Shim Sham Club, where a twenty-four-year-old Louis Prima and his musicians were playing to a mostly empty house as if it were full to the rafters.

With Prima’s olive-colored skin and tight curly hair, Davis mistook him for a Black man, and he worried hiring a Black band leader would keep customers away.

The things we think of when we think of Louis Prima—his sense of humor, his energy, the playful back-and-forth with his bandmates—were all on display. Lombardo darted back to the hotel and dragged his brothers down to the club to see if they were as impressed as he was with Prima’s performance. They already knew Dixieland jazz—the group had been playing it years prior to their arrival in New Orleans—and still they agreed the music they were hearing was so fresh and vital that they entirely forgot to mind being roused from their beds.

Lombardo was so electrified by the performance that he took every opportunity he could to see Prima play during his stay in the city, and the Prima family welcomed him. After some wheedling, he was able to convince Prima to move to New York to take a job at Leon and Eddie’s, a nightspot on Fifty-Second Street where Lombardo had an in. Upon Prima’s arrival, the proprietor, Eddie Davis, informed Lombardo that union issues would prevent Prima from being able to take the gig. Lombardo hurriedly arranged for Prima to get job at the Famous Door, a club just a few doors down, where he quickly became a sensation. When Lombardo returned to Davis to gloat, Davis admitted that the union story was a ruse. With Prima’s olive-colored skin and tight curly hair, Davis mistook him for a Black man, and he worried hiring a Black band leader would keep customers away.

The unique history and culture of New Orleans and its surrounding parishes often confuses and distorts expectations of race and ethnicity. In particular, the history of Black and Italian communities in Louisiana have intertwined and influenced each other in a cross-cultural conversation that contributed to the sound of New Orleans jazz.The French Quarter of the early 1800s was largely defined by its Creole population. Native-born New Orleans residents with roots in the colonial era of Louisiana’s history began to self-identify as Creole (derived from the Spanish criar—“to create” or “to raise”) to differentiate themselves from the waves of Anglo-Protestant immigrants whose arrival threatened their political and cultural power. This Creole identity encompassed both free and enslaved people of African descent as well as Louisiana-born children of French and Spanish descent. Racial tensions persisted; still, visitors to the city marveled at the wide ethnic and cultural diversity of people living in such close proximity. Creole free people of color in particular found themselves occupying an “in-between” space in the social hierarchy of the city. Their social lives often looked superficially similar to their European-descended peers—attending Mass on Sundays and performances at popular theaters and operas—however, their access to these institutions was highly segregated, and their experiences sometimes were closer to that of Black Americans in the Jim Crow–era South.

By the mid-nineteenth century racial tensions began to ratchet up nationally in the lead-up to the Civil War, and despite its multicultural heritage, New Orleans was no exception. As war loomed free Creoles of color were left with a rapidly diminishing “in-between” space.

The end of the Civil War brought with it a new economic reality for the South. In Louisiana the manumission of more than 300,000 formerly enslaved people upended the labor market. The loss of captive agricultural labor, coupled with the devastation of farms, livestock, and transportation infrastructure, hit the sugar industry particularly hard with the number of sugar plantations dropping from 1,200 pre-war to just 175 in 1864. The plantations that survived were navigating a post-emancipation world where freedmen were able to demand wages and better working conditions. The potential pool of workers dwindled as higher-paying jobs, such as those in Kansas’s sugar beet industry, drew people away. And Black workers from across the South left the fields in droves to pursue a life away from the plantations that once enslaved them, moving instead to urban environments, greatly shifting the demographics of cities throughout the nation. By the end of the 1860s, the Black population of New Orleans, for example, had more than doubled in size.Angelina decided that her children—Leon, Louis, and Elizabeth—would play music for the church… The Prima children dutifully suffered through these assignations—but it turned out that churches weren’t the only places music was being played in the city.

Soon planters in Louisiana began to organize, which led to the creation of the Louisiana Sugar Planters’ Association (LSPA). The LSPA wielded significant power and successfully convinced the state legislature to create the Louisiana Bureau of Immigration on March 17, 1866. The bureau was formed to investigate the use of European immigrant labor to work jobs formerly held by enslaved people.

In 1881 the organization began an aggressive marketing campaign, sending agents to Europe to advise potential immigrants on navigating the process of moving to New Orleans. The agents brought with them pamphlets describing the land as a rich, fertile paradise with opportunities for the laborer and the prospective landowner alike. Sicilians already had a history of field labor in Louisiana, with a reputation for a dependable work ethic, and so special entreaties were made to further increase Sicilian immigration. Meanwhile, frustrations among residents in Sicily were mounting. Material conditions for already impoverished Sicilians failed to improve after the unification of the Kingdom of Italy in 1860. Overwhelmed by taxes, military conscription, and the open disdain mainland Italians held for them, thousands of Sicilians were eager to hear out the recruiters, and waves of immigrants streamed into Louisiana each year. The LSPA began running three steamships a month between New Orleans and southern Italy and Sicily, charging forty dollars a person (about $1,200 today) for the two-week journey across the Atlantic.

Although the Sicilian population was explicitly invited to settle in the city, working in the fields marked them as “non-white,” and they were often lumped by embittered white residents into the same socioeconomic category as freedmen, Creoles of color, and other non-Anglo ethnic minorities such as the Jewish and Latino populations. Many Sicilians, who’d arrived without a history of animosity towards their Black neighbors, freely exchanged culture with these other members of their designated socioeconomic class, and white sentiment toward these waves of Sicilian immigrants—and their “failure” to assimilate—became increasingly hostile.

This 1908 photograph shows S. Messina Groceries and Oysters, one of many Italian-run businesses in “Little Palermo.” The Historic New Orleans Collection.

While a number of radical Creoles of color attempted to push back against the racialized prejudices that were now infecting their city, some simply moved to places that might allow a greater degree of freedom—Haiti, Mexico, Cuba, and France. Some of their French Quarter homes, now vacated, were subdivided into low-rent apartments and chiefly leased to the incoming Sicilian workers. By the end of the century, the lower French Quarter (roughly St. Peter Street to Esplanade Avenue) had become an ethnic Italian enclave known as “Little Palermo.” (Like most things in New Orleans, though, the “enclave” had fuzzy boundaries; only 35 percent of Italian-born New Orleans residents lived in Little Palermo even at its peak.)

Ultimately the immigrants that arrived in New Orleans came to seek their own fortune, not to enrich a plantation owner’s. Sicilian workers, squirreling away the profits they made in the cane fields, began to open businesses in the city. Soon, Italian last names sprung up on everything from fruit markets and grocery stores to honky-tonks.

It was in Little Palermo that Louis Prima’s parents met at the turn of the twentieth century. Both were children of immigrants who had arrived in the city during the 1870s. Anthony Prima, Louis’s father, became a distributor for the World Bottling Company (the creator of Ignatius J. Reilly’s beloved Dr. Nut soda), while his mother Angelina (née Caravella) cooked, ran the household, and volunteered at St. Ann’s Church (reconsecrated as St. Peter Claver in 1920). As the Prima family grew, Angelina decided that her children—Leon, Louis, and Elizabeth—would play music for the church, with piano chosen for Leon and Elizabeth and violin for Louis. The Prima children dutifully suffered through these assignations—but it turned out that churches weren’t the only places music was being played in the city.Post-war hardships had fomented a rise in mutual aid and beneficial societies. By 1880 more than 220 of these social clubs existed in the city—and they often found themselves needing music for processions or rallies. Classically trained Creoles of color created orchestras that, with a few changes in instrumentation, could be adapted to brass bands well-suited for parading. One critical support these societies offered was the provision or subsidizing of medical and burial expenses for its members. Burial assistance in particular became a high-stakes affair, with the various clubs seeking to outdo each other with ever more elaborate funeral processions. Merging the existing traditions of military brass funerals with the syncopation of traditional African music, the jazz funeral was invented, and a new sound was developing in the streets and music halls of the city.

By their early teen years, the Prima boys had both fallen in love with that sound. Leon traded in his piano for a cornet and began gigging at jazz clubs in the French Quarter at the age of seventeen. Louis, still too young to play in clubs himself, listened eagerly as his brother practiced with some of the greatest jazz musicians of the era—Black and white alike. Finally he too ditched the instrument assigned to him by his mother, picked up a cornet, and began to develop a sound of his own.

It was the unique social positioning of Sicilian New Orleanians that allowed the Primas the freedom to play in these sessions. Not all ethnic minorities in the city felt comfortable playing with Black and Creole musicians, even when they shared the same socioeconomic class. For example, Godfrey Hirsch, a Jewish pianist-cum-vibraphonist, worked in some of the same dance halls as Prima, but wouldn’t play with a Black band member until 1937, when he joined Louis Prima’s band in Los Angeles.

During the Lombardos’ engagement in New Orleans, Prima once invited them to his family’s home for dinner. Guy Lombardo recalls in his autobiography that the Italian dishes he was served were like those his family made, except with “a touch of Creole.” There’s no reason to believe that the long and winding history of Italians and Creoles was on his mind that night, but forty years after he had that meal he could remember tasting it.

Gregory Theriot wishes he could have found a way to work in that Prima’s mother made her kids work at the family’s snowball stand in the summer.