Colfax Massacre

In 1873 white Louisianans responded to Reconstruction policies with violence, resulting in a massacre that claimed as many as 150 lives.

This entry is 7th Grade level View Full Entry

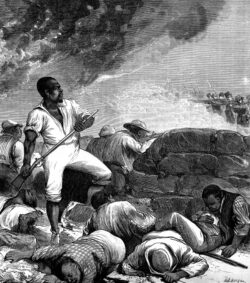

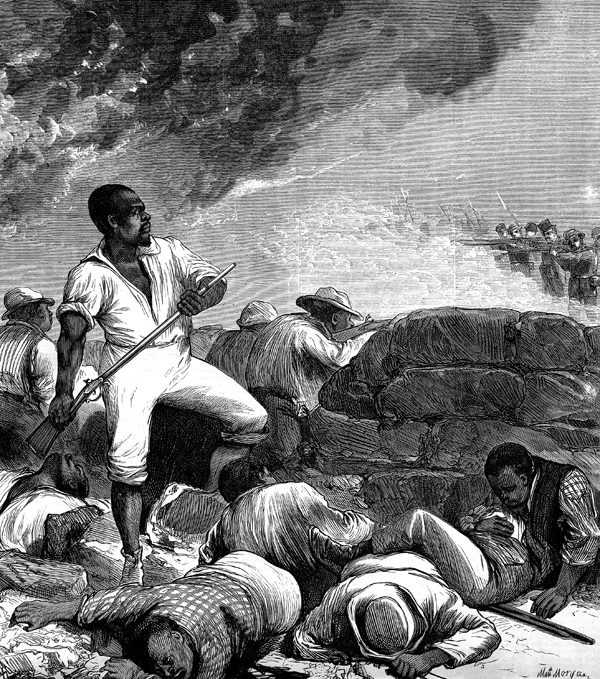

The Historic New Orleans Collection

A battle scene from the Colfax Massacre as depicted in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, 1873.

The Colfax Massacre of 1873 was the deadliest incident of racial and political violence during the Reconstruction era, claiming the lives of at least sixty and perhaps as many as 150 men. African Americans made up all but three of the victims. The massacre elevated the standing of white supremacist organizations in Louisiana and the South. The Colfax Massacre has been remembered as a key event in the establishment of the Jim Crow system, as it led to the Supreme Court decision United States v. Cruikshank in 1875.

How did the Colfax Massacre begin?

The elections of November 1872 produced disputed results and a divided government in Louisiana. In the political contest Radical Republicans allied with Ulysses Grant and Congress faced a “Fusion Ticket” of conservative Democrats and liberal Republicans sympathetic to the cause of home rule. Because neither party recognized the legitimacy of the other side’s claim to victory in the elections, two sets of officials claimed every state office. In Grant Parish, the establishment of dual governments led to a contest for control of the courthouse in Colfax, a rural outpost and stronghold on the Red River.

Republicans claimed the offices of sheriff and judge for party members Dan Shaw and R. C. Register. Democrats insisted that voters favored Christopher Columbus Nash for sheriff and Alfonse Cazabat for judge. In Grant Parish an armed Black militia unit occupied the courthouse, hoping to prevent the Democrats from overthrowing the local Republican government. In response white men from the surrounding area organized in support of the Democrats.

After weeks of mounting tension and incidents of violence, the confrontation at Colfax erupted on Easter Sunday, April 13, 1873. A large crowd of Black people, including women and children, had gathered near the courthouse, where a white force of around 150 men, many of whom had fought for the Confederacy, had also gathered and announced they were going to attack the courthouse. The white militia fired a canon and set the courthouse on fire. Some of the Black men attempted to arrange a surrender, but a conflict broke out between the two militias, resulting in several people being shot and killed, including three white men. Among the white men shot was James West Hadnot, who was thought to be the leader of a local white supremacist organization known as the Knights of the White Camellia.

White participants, in anger over the killings, shot at Black people attempting to escape the burning courthouse. A general slaughter ensued, as the African Americans scattered, and white men rode off in pursuit. Nearby, many Black men emerging from the burning courthouse were captured and detained.

Later that day Black families eager for news of their relatives gathered close to the courthouse while white participants discussed releasing their prisoners. Instead of releasing them, however, a group of militants executed the Black captives. Historians estimate that between sixty and 150 Black people were killed in the massacre.

What were some of the responses to the massacre? How did the Supreme Court respond to the Enforcements Acts?

The state of Louisiana conducted an investigation after the violence and helped with the burial of fifty-nine bodies. James Beckwith, the US attorney in New Orleans, prepared an indictment and commissioned federal marshals to arrest white organizers. To charge the defendants, Beckwith relied upon the Enforcement Acts, which had been passed in 1870 and 1871 to combat organized violence by white supremacist groups such as the Knights of the White Camellia and the Ku Klux Klan. In the wake of the massacre, nearly one hundred white men were indicted but only nine were charged under the Enforcement Acts. Three were convicted on charges of conspiracy but those charged appealed. The case went to trial as United States v. Columbus Nash, and hundreds of Black and white witnesses testified in the case, which was later renamed United States v. Cruikshank.

In this case the Supreme Court tossed out the convictions and invalidated key sections of the Enforcement Acts. As a result no one was punished for the Colfax Massacre, and after 1875 the responsibility for prosecuting racial and political crimes fell to state—not federal—courts. As the Reconstruction era ended, southern courts and elected officials increasingly favored white supremacy and turned a blind eye to Klan-style violence and repression.

Historical Marker

In 1950 the Louisiana Department of Commerce and Industry erected a state historical marker on the site of the Grant Parish Courthouse under the title “Colfax Riot.” The marker declares, “On this site occurred the Colfax Riot in which three white men and 150 Negroes were slain. This event on April 13, 1873 marked the end of carpetbag misrule in the South.” The marker, long a subject of community controversy due to its gross misinterpretation of the event and its consequences, was removed by the Office of Louisiana Economic Development (successor to the state office that erected the marker) on May 15, 2021. A new memorial to the victims of the massacre was unveiled on the 150th anniversary of the massacre, on April 13, 2023.