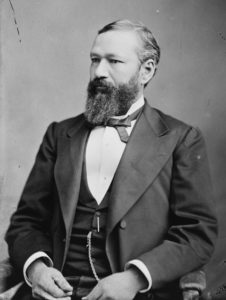

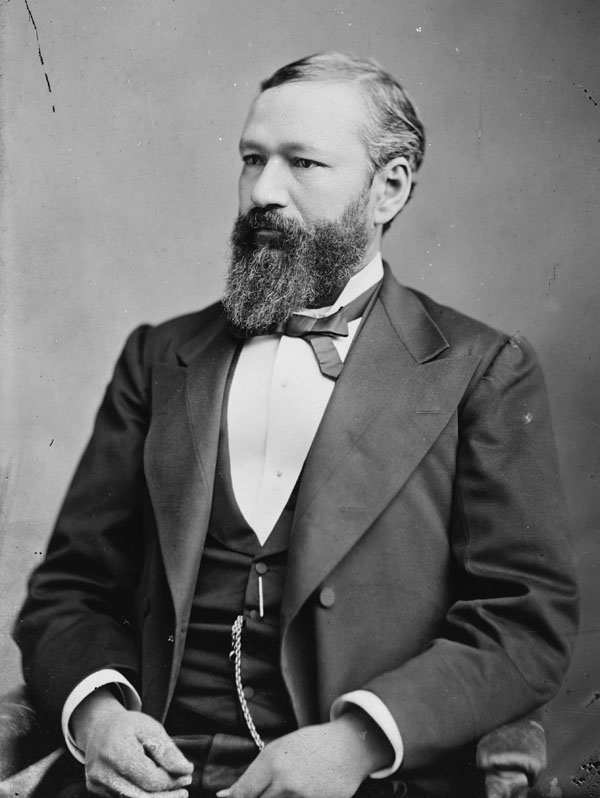

P. B. S. Pinchback

After serving as a Union officer in the Civil War, P. B. S. Pinchback became the first Black governor in the United States.

This entry is 7th Grade level View Full Entry

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

A portrait of Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback, the only African American to serve as governor of a southern state during Reconstruction.

The son of a white southern planter and a formerly enslaved woman, Pinckney Benton Stewart “P. B. S.” Pinchback became the first African American to serve as governor of an American state. Before his political career during the Reconstruction period, Pinchback served as one of the Union Army’s few commissioned officers of African descent during the Civil War, and in later years he helped establish Southern University in Baton Rouge. He was a politician who often focused on achieving realistic goals rather than symbolic victories.

What were P. B. S. Pinchback’s early life and military career like?

Born in Macon, Georgia, in 1837, Pinchback spent most of his boyhood on his father’s plantation in Holmes County, Mississippi. His father sent him to school in Cincinnati, Ohio, the abolitionist hub of the upper Midwest and the home of a growing community of free Black people and runaways. The unexpected death of his father put young Pinchback, as well as his mother and siblings in danger of being re-enslaved by white relatives who disinherited the mixed-race family. Around 1850 they fled to Cincinnati, where their future was uncertain.

As a young man Pinchback worked aboard boats on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, and he married Nina Hawthorn of Memphis, Tennessee, in 1860. He arrived in New Orleans not long after the Union retook the city in 1862, a time of turmoil and opportunity. When Major General Benjamin F. Butler announced that he would raise regiments of “Native Guards” from the city’s free Black population, Pinchback immediately applied to recruit his own company. Although he was the only officer of color in the original Native Guards who was neither a native New Orleanian nor an Afro-Creole, he encountered little difficulty during recruitment. Upon entering service at the end of August, Pinchback assumed command of the unit.

In early 1863, to rid the army of nonwhite officers, the Union army began requiring Black officers to pass fitness tests. In September 1863, while stationed at Fort Pike outside of New Orleans, Pinchback resigned rather than take the exam.

How did Pinchback get involved in Louisiana politics?

Pinchback’s political career took off during the early years of the radical movement in Reconstruction-era New Orleans. When the Reconstruction Acts passed in 1867, a new state constitutional convention was set up. Pinchback, as the leader of the Fourth Ward Republican Club, gained his first meaningful office as a delegate to the convention, where he revealed his preference for practicality over political beliefs. This attitude, along with his on-and-off backing of Henry Clay Warmoth, made him a target of suspicion by the city’s Afro-Creole political elite—a group that Pinchback would never belong to—but he became popular among newly empowered freedmen. During the convention Pinchback authored what became Article Thirteen of the 1868 Constitution, which guaranteed equal access to public conveyances, such as streetcars and trains, regardless of race. During this time he also became the sole owner and primary editor of the Weekly Louisianian, a Black newspaper.

When Pinchback was elected to the Louisiana legislature as a state senator in 1868, he became fellow Black politician Oscar Dunn’s main rival. When Warmoth was elected governor that same year, he appointed Dunn lieutenant governor, but their relationship was strained and got worse when Dunn aligned himself with the governor’s Republican rivals based at the United States Custom House in New Orleans. During this time Pinchback served as president of the state Senate, where he earned a reputation as a capable but not always honest legislator. He also formed a powerful political relationship with Warmoth.

Warmoth’s rivals at the Custom House had tried to impeach Warmoth so that they could seat Dunn in his place. When Dunn died suddenly in the late summer of 1871, Warmoth moved quickly to have Pinchback elected as his lieutenant governor. Over the summer of 1872, though, Warmoth lost control of the party as his Custom House rivals solidified support in heavily African American parishes and wards with the help of C. C. Antoine and other Black Republicans. As a result, a man from Illinois named William Pitt Kellogg became the party’s nominee for governor in 1872, with Antoine nominated for lieutenant governor.

How did Pinchback become governor, and what challenges did he face during his term?

As Warmoth became the leading champion of the Liberal Republican movement in Louisiana, Pinchback parted ways with him over both national and state party politics. Pinchback stayed a solid supporter of President Ulysses S. Grant. In fact, he considered his role in nominating Grant at the National Republican Convention in 1868 one of his proudest moments. Although Pinchback resented the Custom House faction, he trusted the so-called Fusion Party even less, despite Warmoth’s decision to throw the support of the state’s Liberal Republicans behind them. This final rift between Warmoth and Pinchback opened the door to Pinchback’s becoming governor. After the election the Custom House faction impeached Warmoth and elevated Pinchback to governor, a post he held for thirty-six days from December 1872 to January 1873.

Pinchback later claimed victories in disputed elections to both the US Senate and the US House of Representatives but failed to persuade either chamber to seat him. To pursue new objectives, he returned to New Orleans. Pinchback, like his one-time ally Warmoth, remained influential in Republican Party circles after Republican power collapsed in 1877 with the end of Reconstruction. Among other achievements, he worked with Governor Francis T. Nicholls to create Southern University, an institution for Black students, and served on its board of trustees.

Later in his career, Pinchback held several positions at the US Custom House, earned a law degree at Straight University (which was a precursor to Dillard University), and became a practicing attorney. He left New Orleans by the 1890s, moving first to New York City and then to Washington, DC. Pinchback died in 1921 and was buried in Metairie Cemetery just outside New Orleans.