Urban Slavery in Antebellum Louisiana

Enslaved people in Louisiana’s cities were engaged in nearly every labor role, from domestic service to dentistry.

This entry is 7th Grade level View Full Entry

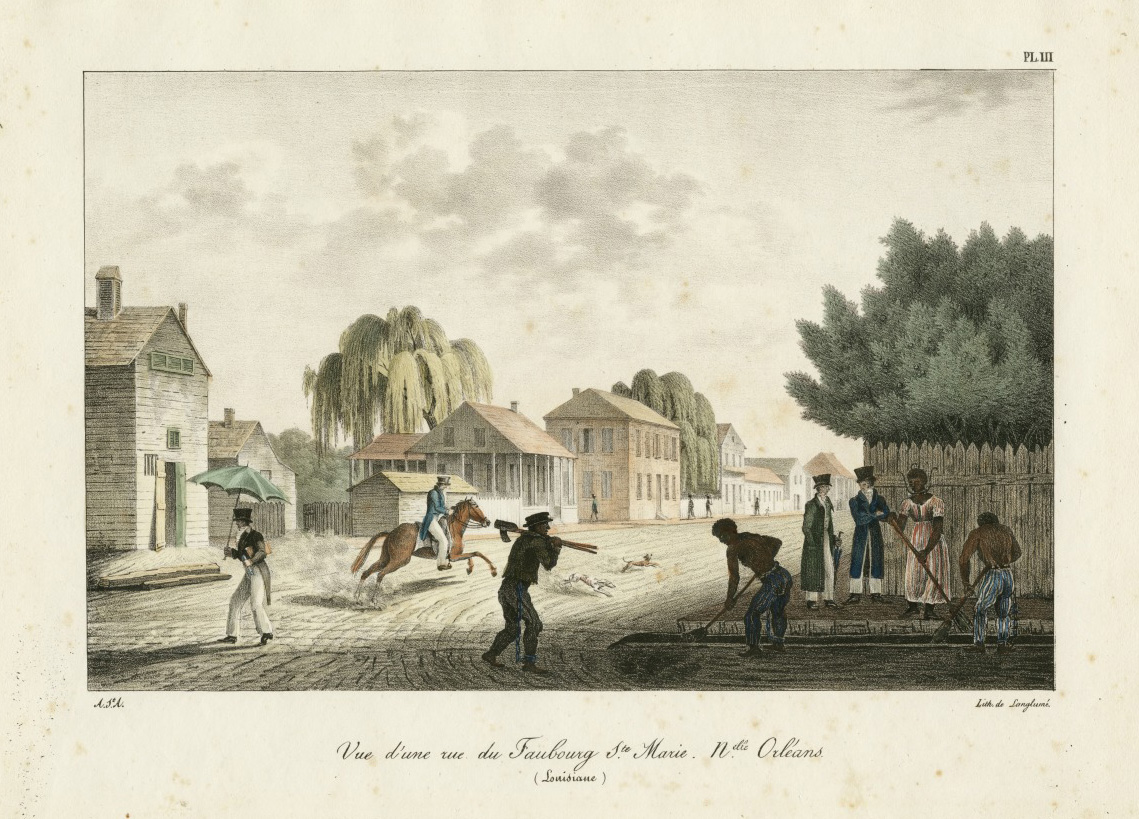

The Historic New Orleans Collection

A lithograph entitled "Vue d'une Rue du Faubourg Ste. Marie" depicts people at work in the streets of the present day Central Business District, 1821.

How were urban slavery and plantation slavery different?

Today most people associate slavery with plantations. However, slavery was practiced everywhere in the South during the antebellum era, including cities. About 5 to 10 percent of enslaved people in the United States lived in cities. They experienced different working conditions, living standards, and methods of racial control than those in rural areas.

By 1840 there were more than twenty-three thousand enslaved people living in New Orleans (nearly one-fourth of the city’s total population). New Orleans was the largest and wealthiest city in the Deep South during the antebellum period. In addition, New Orleans was the second busiest immigration port in the United States and the world’s fourth busiest commercial port. Outside of New Orleans, Louisiana was mostly rural.

Although antebellum slavery was mainly a rural institution, cities played an important role in the plantation economy. The business of the domestic slave trade took place in cities. New Orleans’s slave market—where more than one hundred thirty-five thousand people were bought and sold between 1804 and 1862—was the biggest in the country. In cities the cash crops grown by enslaved people on plantations were repackaged, sold, and shipped to other areas of the country as well as to overseas markets like England and France. Cities were also vital financial centers where banks loaned money to buy both land and people.

What types of labor did enslaved people do in cities?

Most urban enslaved people were “domestic slaves,” working in their enslavers’ homes. These enslaved people cleaned homes, tended gardens, bought groceries, cooked and served meals, washed and mended clothes, and raised children. Enslaved domestic workers were so common in New Orleans that it was rare to see any white people in the city’s marketplaces. According to one resident, “almost the whole of the purchasing and selling of edible articles for domestic consumption” was performed by enslaved people. Since domestic labor was usually assigned to women, nearly two-thirds of all enslaved people in New Orleans were women.

Enslaved men usually worked difficult manual labor jobs in cities, such as construction work. They paved streets, dug sewers, laid pipes, and built levees and wharves. New Orleans’s antebellum economy was based on the city’s port. Many enslaved men worked the docks by loading and unloading cargo, stocking warehouses, and repairing ships in dry docks. These enslaved dockhands often worked alongside foreign-born immigrants, white people, and free men of color.

There were also enslaved carpenters, weavers, plasterers, shoemakers, blacksmiths, tailors, and bricklayers in cities. These highly skilled artisans were valued by their enslavers and their communities, and they often enjoyed privileges and independence unavailable to most other enslaved people. They were typically subjected to less daily supervision and physical violence. They were often able to earn spending money by performing their trade after hours, or because they were allowed to keep a portion of the wages they produced.

Most of the largest slaveholders in antebellum New Orleans were factories and businesses. The New Orleans Levee Steam Cotton Press owned 104 people in 1850. The D’Aquin Brothers’ Bakery held forty-seven enslaved bakers, confectioners, and pastry chefs. The New Orleans Gas Light Company, which operated the city’s gas lines and streetlamps, owned thirty-five enslaved technicians, repairmen, and lamplighters. There were even a handful of enslaved skilled professionals in New Orleans. At least one enslaved dentist, Charles Johnson, lived in the city and drew enough business that a group of frustrated white dentists petitioned for his arrest in 1860. In short, urban enslaved people were engaged in virtually every employment and industry.

Where did urban enslaved people live?

Rural enslaved people tended to live in cabins apart from the main house. Urban enslaved people usually lived closer to their owners. Due to the risk of fire, antebellum townhouses usually had freestanding kitchens, detached from the main residences. Apartments for enslaved people were often located on the second story of this rear structure. In cities space was always limited, and many enslaved people lived in attics, closets, foyers, stables, and hallways. A guest at one prominent New Orleans hotel complained that the waiters, who were all enslaved, “had no beds” and slept “like dogs, in the passages [halls] of the house.”

What was the hiring-out system and who did it benefit?

The hiring-out system, though not unique to urban areas, was widely practiced in cities. In this system, slaveholders could rent their surplus enslaved workers to employers who were shorthanded. The practice allowed urban slaveholders to maximize their profits by reallocating their labor supply, according to fluctuating demand. Slaveholders and city leaders were concerned that the hiring-out system undermined racial control by weakening the relationship between enslaved people and their owners. Every slaveholding city tried regulating the practice by requiring slaveholders to register the enslaved people they hired out with the city government.

Lawmakers were even more alarmed by the practice of “self-hiring.” This arrangement allowed enslaved people to negotiate their own wages and rent their own homes. They would periodically return to their owner—weekly, monthly, or even as rarely as semi-annually—to deliver a portion of their earnings. Slave self-hiring was technically illegal, but the laws prohibiting it weren’t regularly enforced.

On rare occasions, hired-out and self-hired enslaved people were able to save enough money to purchase their freedom. For example, Louisiana’s first Black Lieutenant Governor Oscar James Dunn became free when his stepfather, an enslaved carpenter, purchased freedom for himself and his family. The growth of Louisiana’s population of free people of color alarmed state lawmakers. Manumission was severely restricted after 1830 and outlawed altogether in 1857.

How did enslaved people in cities experience daily life?

Cities also provided access to social and cultural activities, particularly on Sundays, traditionally a day of rest for enslaved people. One Sunday visitor to New Orleans described witnessing enslaved “men, women and children assembled together on the levee, drumming, fifing, and dancing, in large rings.” Another visitor on a Sunday described “a crowd of 5 or 600 persons . . . formed into circular groups” within a public square to dance, sing, and chant. By allowing the exchange of West African, European, and Native American traditions, these gatherings contributed to the development of Voudou, second lines, and jazz. New Orleans’s government banned assemblies of enslaved people in 1817, except in places and times designated by the mayor. As a result, weekly (and officially sanctioned and police-supervised) assemblies were held in Congo Square.

Many businesses catered to enslaved people. One New Orleans newspaper, The Daily Crescent, complained that the churches, restaurants, barbershops, saloons, and ice cream shops that served the enslaved were so crowded on Sundays that it was difficult for “the white passer-by” to “elbow” through the crowds standing outside. Selling alcohol to enslaved people was illegal, but many taverns did so anyway.

How was slavery enforced in cities, and how did enslaved people resist?

Enslaved people in cities had access to resources and freedoms not available to them in rural areas. They lived and worked alongside immigrants, poor white people, and free Black people, which promoted the exchange of information and antislavery thought. “[I] would rather live in New Orleans than any other place in the world,” remarked one Louisiana fieldhand. Many Louisiana slaveholders believed that cities undermined racial control. “The atmosphere of the city is too life-giving, and creates thought,” one New Orleans visitor remarked. “The city, with its intelligence and enterprise, is a dangerous place for the slave. He acquires knowledge of human rights, by working with others who receive wages when he receives none.”

Rural enslaved people often fled to the cities. Some found work in the cities, while others tried to escape the South entirely by sneaking aboard outgoing ships. Southern city governments built elaborate policing systems to pursue these urban fugitives and counteract the freedoms that urban enslaved people enjoyed. Slaveholding cities had pass and curfew systems. In New Orleans and Baton Rouge, any enslaved person found outdoors without a signed pass, or found outdoors after dark, could be arrested, whipped by the police, and jailed until their owner reclaimed them. Louisiana cities also built prisons for enslaved people. New Orleans’s slave prison was very large. By 1840 there were usually some two to three hundred incarcerated enslaved people within the city on any given day.

Yet urban enslaved people developed new strategies for evading law enforcement. They sneaked into taverns and illegal gatherings to avoid police. They forged slave passes to get around pass and curfew regulations. On occasion enslaved people even got friends or family out of prison by paying poor white people to impersonate their owners.

A rise in immigration rates and better access to low-cost labor led to rapid declines in urban slaveholding in the late antebellum period. From a peak population of 23,448 enslaved people in 1840, New Orleans’s enslaved population declined to 13,385 by 1860. In many of New Orleans’s manual labor and service industries, immigrant wageworkers mostly replaced enslaved people by the Civil War.