The Life and Work of Elizabeth Brandon

An elegant refugee who became an unsung hero of Louisiana French folklore

Published: November 30, 2023

Last Updated: February 29, 2024

Luc Lacourcière collection, Université Laval

Elizabeth Brandon at work on her dissertation in February 1955.

A cursory look at the works of folklorists in the twentieth century who collected, transcribed, and catalogued the unique songs, folktales, superstitions, and folk beliefs of the Cajuns and Creoles in the Bayou State will reveal that most of this work was done by local scholars who tended to focus on their own native regions. It’s not hard to imagine why, since people are most at ease describing their culture and traditions to someone who resembles them. In many ways Elizabeth Brandon was an outsider in her field: as a woman, a devout Jew, and an immigrant. One can imagine the challenges she would have faced in conducting research among the Cajuns and Creoles of Louisiana regarding intimate cultural topics involving traditions, beliefs, folk healing, and religion.

. . . Brandon took a wide-lens perspective that included specific customs according to the time of year, riddles, folksongs, superstitions, and vernacular medicine.

However, while this well-dressed wordsmith, speaking in the French dialect she learned while studying at the Sorbonne in Paris, may have seemed like she was from another planet to a farmer in Erath, the sound recordings of her interactions with the Cajuns of Vermilion Parish demonstrate a remarkable affinity and closeness with her informants. Her dissertation is an impressive two-volume work covering the folksongs, tales, superstitions, and vernacular medicine of Vermilion Parish; she made her career at the University of Houston as a specialist in linguistics and romance languages. The Erath farmer would be right—her life began a world away. But through chance, tragedy, perseverance, and a life-long passion for learning, Brandon found her way to the heart of Cajun and Creole country, a region that she would come to devote much of her career exploring.

From Tragedy to New Beginnings

One of three children, Elizabeth Brandon (née Kaplan) was born in 1913 in the town of Vawkavysk, situated in Poland at the time, although it is now part of Belarus. Raised in the Ashkenazi Jewish tradition, she learned several languages in her youth, including Polish, English, Yiddish, and French. She was also a gifted musician, studying at the conservatory in Vilnius.

By her mid-twenties, Elizabeth’s future seemed bright. She was a newlywed studying French at the Sorbonne in Paris. But 1939 proved to be a devastating year for Elizabeth’s family. During the German-Soviet invasion of Poland, Elizabeth’s mother Chasia and her sister Naomi were imprisoned in concentration camps, including Auschwitz, where her mother was murdered by the Nazis. Her father Samuel, a banker, was sent to Siberia, where he suffered imprisonment and forced labor. Though Elizabeth and her husband, Sylvan Borschevsky, were in relative safety while she studied in France, the couple decided to emigrate to the United States. At the time the United States maintained a ban on Polish refugees. But because Sylvan was born in Montpellier in southern France, they were eligible for entry.

By 1940 Elizabeth and Sylvan were settled in Houston, where they changed their surname from Borschevsky to Brandon. After serving as a physician in the Air Force, Sylvan became one of the first ophthalmologists in the area, and Elizabeth first worked in an administrative position for Shell in Houston. Soon thereafter they adopted two children, Michael and Anne. Sylvan was able to locate Elizabeth’s sister Naomi and her father Samuel and bring them to Houston. (Naomi Warren went on to become a successful businesswoman and active community member serving on the boards of Holocaust Museum Houston and the Jewish Federation of Greater Houston.)

Elizabeth Brandon (right) and Agathe Lacerte (left), the sister of renowned folklorist Luc Lacourcière. Luc Lacourcière collection, Université Laval.

Although her academic pursuits were interrupted by World War II, Brandon never gave up on her desire to continue her studies. In the early 1950s she began her doctoral degree at Université Laval in Quebec, Canada, often working by correspondence. Her dissertation director was the renowned folklorist Luc Lacourcière, who made Université Laval a major hub for folklore studies in North America. Marius Barbeau, another eminent scholar in the field, also served on her dissertation committee.

The Career and Legacy of Elizabeth Brandon

Her 1955 doctoral dissertation, entitled “Mœurs et langues de la paroisse Vermillon [sic] en Louisiane” (Customs and Language of Vermilion Parish in Louisiana) is a sweeping study of the French-speaking culture of that region. Rather than adopting a narrower scope focused on specific types of folktales, as was common during her time, Brandon took a wide-lens perspective that included specific customs according to the time of year, riddles, folksongs, superstitions, and vernacular medicine. She recorded several traiteurs (“treaters” or healers) describing techniques and practices nearly forgotten today. It’s important to note that since most of her interviewees were already advanced in age, the testimonies that she recorded in the early 1950s often described an earlier time, when people traveled mostly by horse and buggy and were predominantly only fluent in French.

In addition to Brandon’s impressive body of written work, now accessible at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, a large collection of her audio recordings is also available at the Center for Louisiana Studies, located in the newly renovated Roy House on the university’s campus. Chris Segura, archivist at the Center for Louisiana Studies, noted, “Elizabeth Brandon’s collection is one of the jewels of the Center for Louisiana Studies’ archival holdings. Her recordings are an immersive look into the French language, songs, jokes, and stories being sung and recited in Vermilion Parish in the early 1950s.”

While her recordings and transcriptions offer a detailed account of her collections, we now also have access to a behind-the-scenes view of her research activities and work process. Brandon’s notes, correspondence, and readings, written in French and English, contain a wealth of insight into Brandon’s research goals and the kinds of questions that she was asking. These papers were processed during the COVID-19 lockdown and have been made available to the public in the Special Collections at Edith Garland Dupré Library at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. Dr. Zachary Stein, who was Head of Special Collections at the time and who processed the collection, described the Elizabeth Brandon Papers as “a gold mine for anyone interested in the French language and Francophone culture. These subjects are the pulse of south and southwest Louisiana, and Dr. Brandon’s working files help researchers tap into the richness of this diverse region.”

Reading her notes and correspondence, one senses a certain distance from other researchers in Louisiana at the time, as Brandon was a kind of outsider. However, she maintained an astonishing network of renowned researchers through her correspondence, and she maintained close friendships with some of the shining stars of folklore studies and ethnomusicology, as evidenced by her letters. For example, it would be natural to assume that the folksongs that Brandon collected in Vermilion Parish might be transcribed and notated by a local researcher familiar with the repertoire. However, Brandon enlisted one of the period’s foremost ethnomusicologists, Marguerite Béclard d’Harcourt, for this task. Postcards and letters detail the painstaking process of mailing reels and field notes across the Atlantic Ocean to be transcribed, verified, and mailed back again. Intermingled with scholarly correspondence are friendly postcards, often highlighting Brandon’s generosity and taste for the finer things in life. At times d’Harcourt thanks Brandon for gifts such as bouquets of flowers or a new fur coat delivered to her home in Paris’s 17th arrondissement.

Another prominent figure appearing in her correspondence is the renowned folk singer Joe Hickerson, who served as director of the Archive of Folk Song at the American Folklife Center of the Library of Congress. Hickerson was keenly aware of the value of Brandon’s recordings, often requesting more information or copies of certain materials. To this day, the Library of Congress maintains copies of Brandon’s audio recordings from the 1950s.

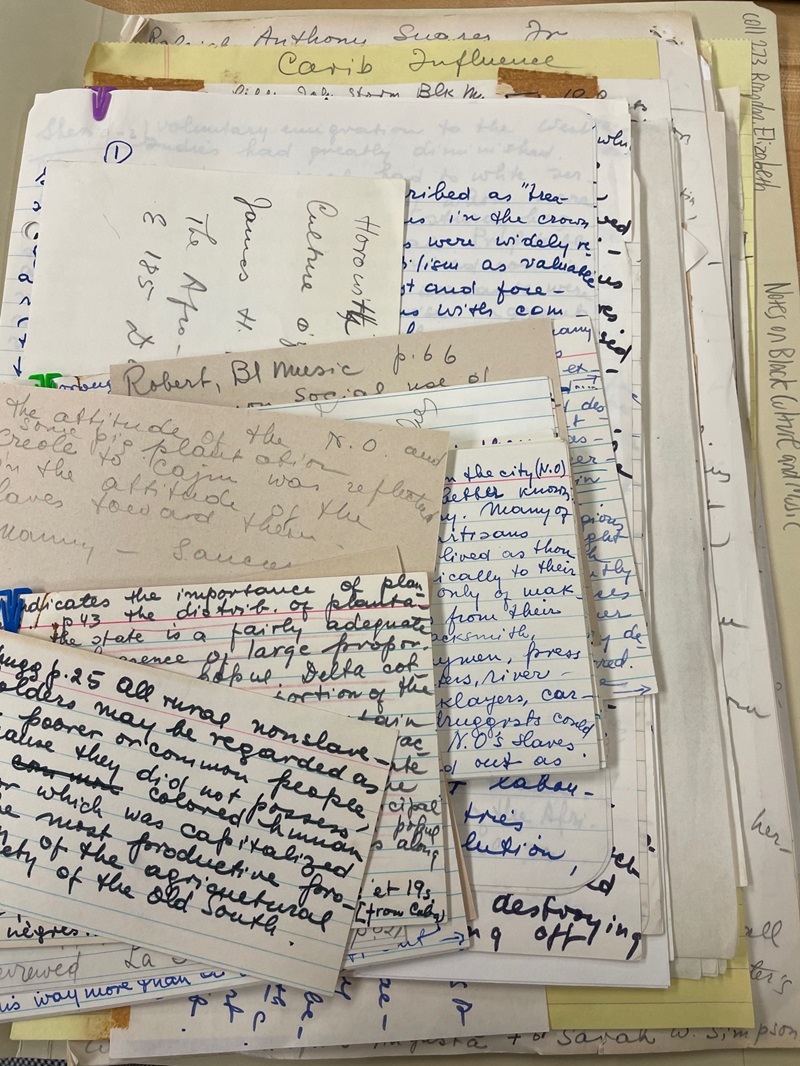

A sampling of Brandon’s meticulous note-taking. Elizabeth Brandon Papers, University of Louisiana at Lafayette.

Perhaps even more importantly, Brandon’s personal notes reveal how her own background informed and deepened her interest in Louisiana. As she writes, she herself embodied the rich cultural melting pot of America, and she found abundant evidence of this cultural mix in Acadiana. She contemplates the impact of African and Caribbean influence on Cajun culture, convinced that their impact was much greater than what was openly acknowledged at the time. Perhaps her outsider status motivated her marked effort to include Black Creole informants as much as their white Cajun counterparts in the deeply segregated context of 1950s Louisiana—a rarity in the scholarship of her time. At a time when many folklorists were preoccupied with preserving vestiges of the Old World, Brandon was particularly forward-thinking in her obsessive questioning of adaptations of folk material to the Louisiana context, considering how and why certain elements had persisted or changed over time.

Arguably the most poignant artifact of the Elizabeth Brandon Papers is a tattered spiral bound notebook containing the “genesis” of what would be a new anthology of folksongs collected in Vermilion Parish, set to be published in 1976. In this handwritten draft of her unfinished manuscript, Brandon writes that “it is only fitting that this book should see the light in 1976, on the occasion of the Bicentennial of my adopted country. In a way, I myself represent the diversity and multiculturalism that is being emphasized this year. Born into an Ashkenazi-Jewish traditional family, raised and educated in Yiddish, Russian, Polish, French—French Canadian—cultures, settled in Texas, I chose yet another ethnical [sic] group to study—the French Louisianian.” In her own words, she represented the “united nations” of various ethnic groups that could meet, influence, and appreciate one another. Though her origins were so far-removed and seemingly different from the Cajun and Creole cultures that she studied, she turned these distinctions into strengths that helped her bridge the gap between this unique region and the rest of the world. In so doing, she was able to accomplish in her career what folklore aspires to achieve: celebrating our diverse specificities and appreciating our commonalities through the magic of storytelling.

This article was made possible through research supported by the Jamie and Thelma Guilbeau Fellowship at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, which encourages researchers to conduct work based on the university’s special collections. The author also expresses heartfelt thanks to Dr. Michael Brandon, who patiently provided personal details and context regarding his mother’s life and career.

Nathan Rabalais is an associate professor of francophone studies at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette and holds the Joseph P. Montiel Endowed Chair in Modern Languages. He specializes in the folklore, literature, and popular culture of francophone North America, particularly in Louisiana and the Acadian communities of maritime Canada. His latest book Folklore Figures of French and Creole Louisiana (2021) was published with Louisiana State University Press with the support of a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship. Nathan is also fulfilling a five-year term as a research fellow of the Center for Louisiana Studies (2020–25).