NAACP in Louisiana

The NAACP, a national organization founded in 1909 to fight for citizenship rights for Black Americans, opened its first Louisiana branch in 1914.

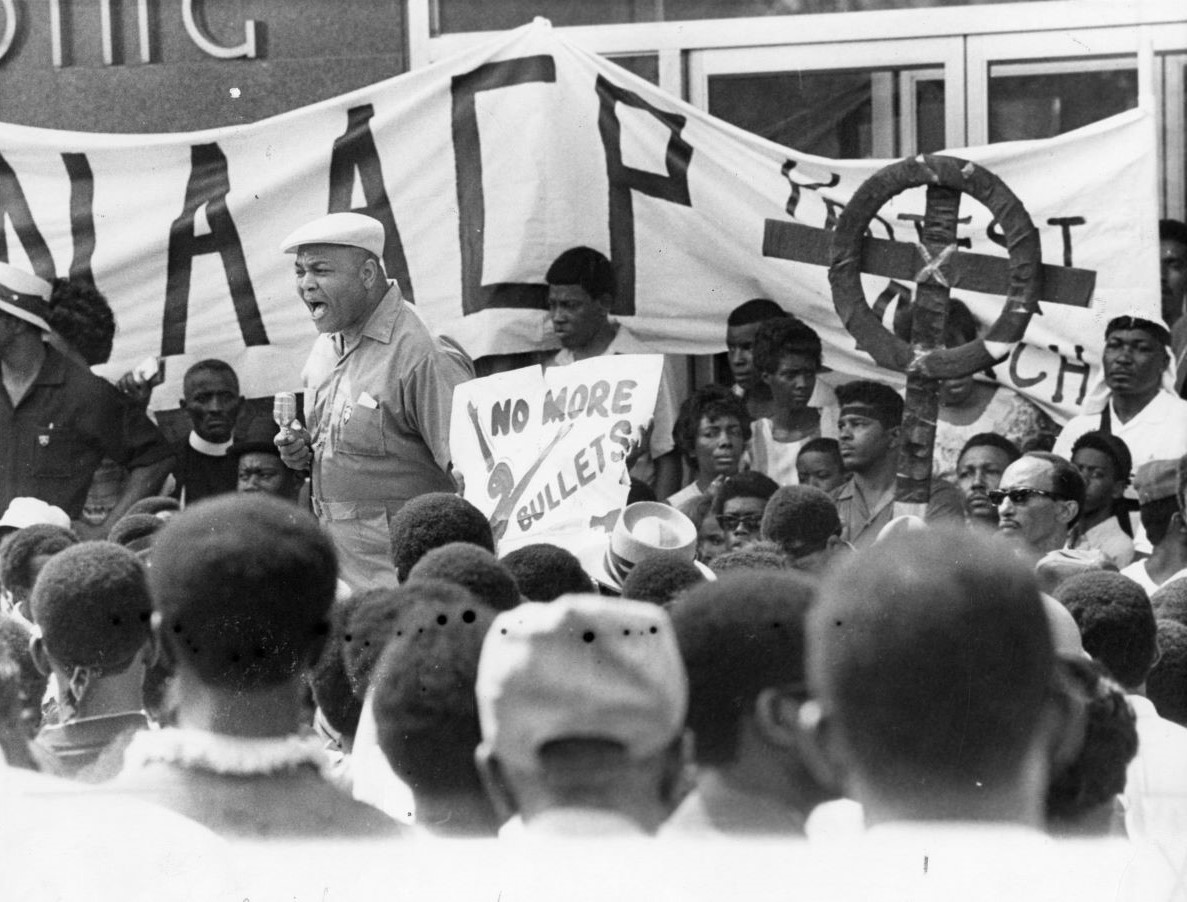

The Advocate / Capital City Press

NAACP protests police brutality and the killing of Southern University student James Oliney by Baton Rouge police officer Ray Breaux.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a national organization founded in 1909 to fight for citizenship rights for Black Americans. The organization continues to fight injustice today, expanding its mission to support minority rights, including for all people of color, and issues like reproductive rights and marriage equality. The NAACP is an integrationist organization, focused on constitutional rights for minorities, and is renowned for its involvement in the US Supreme Court decision, Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which legally desegregated schools. The organization has branches across the United States that created extensive national, regional, state, and local networks. These branches became the foundation of the civil rights movement (1954–1968) and ongoing contemporary civil rights struggles. The earliest Louisiana branch was founded in Shreveport in 1914, with New Orleans (1915) now being the oldest and longest-operating branch in the South.

Early Membership, Women, and the Black Middle Class

Early membership in state NAACP branches was often middle class and included professionals who catered to the segregated Black community, such as teachers, lawyers, dentists, undertakers, and postal workers. Without such grassroots support the NAACP would have struggled to survive in the hostile racial environment of the 1920s and 1930s, especially in Louisiana’s smaller towns and cities and rural areas. With low initial membership in Louisiana, the NAACP grew to be a strong presence in the state due to various factors, including national membership drives that focused on the South. (The NAACP became a majority-Black membership organization in the 1920s due to campaigns by author and national NAACP Executive Secretary James Weldon Johnson as well as key support campaigns, such as lobbying for federal antilynching legislation and teacher salary and school funding equalization cases.) For example, New Orleans went from fifty-six members in 1917 to 750 by 1934, and post–World War II membership numbers reached 8,077 by 1945. The increase reflected the organization’s increasing popularity due to the war effort’s emphasis on equality and democracy and the belief that NAACP strategies were effectively working toward integration and full Black citizenship. Other cities and towns had membership numbers fewer than one hundred in the interwar period, but the war increased numbers significantly. By 1945 Baton Rouge had 1,671 members, Monroe had 1,059, and Shreveport 212.

The Louisiana NAACP integrated women into its main branches from its earliest days. There were opportunities for women in elected posts, executive committee membership, and leadership roles, such as Georgia Johnson of the Alexandria branch, who was chair of the branch’s legal redress committee from 1941 to 1944, and Delphine Dupuy, who was vice president of the Baton Rouge branch from 1929 to 1934. Dyan F. Cole became the first female president of the New Orleans branch in 1975, serving for one year.

Early Campaigns

The NAACP’s Louisiana branches campaigned to integrate libraries, parks, beaches, stores, and accommodations. They recorded and fought police brutality, lynching, and violence against Black Louisianans. In addition, branch fundraising and data collection at local and state levels enabled national NAACP campaigns, such as the fight for a federal antilynching bill. and lobbying of federal and state governments.

Voter registration campaigns were a constant branch activity in Louisiana despite economic disincentives, violence, and poll taxes. Poll taxes were repealed in 1934, but literacy tests, or so-called “understanding clauses,” continued to keep Black voters off the rolls. In 1931 the New Orleans branch filed a case to challenge literacy tests in Louisiana that prevented Black citizens from registering to vote, but the case failed. In 1942 several Black activists in New Orleans, including Ernest J. Wright, attempted to vote in the Democratic Party primary but were turned away. Excluding Black primary voters meant that the Democratic Party could control who became a candidate and, therefore, who won elections. In 1943 the Louisiana NAACP sought to challenge the white primary system in the state, yet by 1944 the US Supreme Court struck it down in the NAACP’s Texas case, Smith v. Allwright.

In 1946 President of the Louisiana State Conference of NAACP Branches Daniel Byrd organized a coalition of religious institutions, unions, and activists to register twenty thousand Black people (only four thousand registrations succeeded due to forms allegedly being filled out incorrectly). By 1956 Louisiana’s Black electorate totaled 160,000, including 25,000 in New Orleans. This number surpassed 1896 figures before the introduction of disfranchisement laws, although voters were too dispersed around the state to form an influential voting bloc. In 1956 Monroe officials purged electoral rolls after NAACP registration successes. It would take the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965 to make more substantial headway for Black enfranchisement in Louisiana.

The Great Depression and World War II

The Great Depression saw NAACP branches investigating New Deal federal relief administered at the state level. In the Deep South, New Deal agencies like the Civilian Conservation Corps were segregated, and they often excluded or gave unequal welfare relief to Black citizens. Some NAACP branches endeavored to secure and integrate jobs for Black Louisianans in the defense industry after the establishment of the Federal Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) in 1941. In New Iberia, Branch President J. Leo Hardy and Secretary Franzella Volter, a schoolteacher, along with other prominent members, were run out of town in 1944 for opposing racial discrimination in welding training and appealing to the FEPC for redress. Other places secured a small number of skilled defense jobs, such as the Baton Rouge branch, which sought to investigate defense jobs to ensure an integrated workforce for carpentry jobs.

Alexandria, surrounded by five military training camps, was confronted by a substantial rise in population and racial tensions during World War II. In 1941 the city’s branch, run by Georgia M. Johnson, investigated police brutality toward Black soldiers and civilians, attempted to get Black people onto juries, and sought access to defense and civil service jobs. Johnson also investigated the January 1942 riot instigated by the unfair treatment of soldiers in the surrounding segregated military camps and by the arrest and abuse of Black soldiers by Alexandria police. The riot resulted in more than three thousand arrests and at least twenty-eight Black people shot.

Teachers’ Equalization Case and Integration of Education

A key Louisiana NAACP campaign included legal cases to equalize Black teachers’ salaries with those of white educators. The cases were directed by New Orleans NAACP attorney A. P. Tureaud, the Louisiana Colored Teachers Association (which financed the cases), and Thurgood Marshall, who served as special counsel for the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund. The initial case was McKelpin v. Orleans Parish School Board (1941), which led to other cases against local school boards. By 1948 all of Louisiana’s Black teachers had gained pay equality. Branch focus on such cases facilitated a statewide NAACP conference to pool resources and legal expertise.

With the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown decision, the Louisiana NAACP forced the state legislature via the courts to implement a school integration policy in 1959. Schools started integrating in Louisiana by 1960, leading to the New Orleans school crisis. The rest of the state followed over time, but even with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, progress remained slow.

Youth Councils

Branch youth councils were a way to get young people to engage with the NAACP’s integrationist philosophy and were integral to early campaigns. In Baton Rouge in 1938 the council organized a campaign to ensure that Black consumers bought from Black businesses. In the early 1960s they joined more direct-action groups, such as the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE, whose Freedom Rides concluded in New Orleans in 1961), as direct action became more popular with youth movements over the NAACP’s more legalistic tactics. Raphael Cassimere became New Orleans NAACP Youth Council president from 1960 to 1966 and was instrumental in reviving the council and organizing boycotts to attain Black employment in the city.

Baton Rouge Bus Boycott

An important campaign in Louisiana was the Baton Rouge bus boycott that prefigured the 1954 Montgomery bus boycott to desegregate public transport. On June 15, 1953, twenty-three-year-old Martha White sat behind a driver on a bus and was arrested. The boycott lasted five days. Baton Rouge Branch President B. J. Stanley helped facilitate the boycott using several private cars. Horatio Thompson, the first Black man in the South to own an Esso gas station franchise, provided fuel at cost. (Thompson had joined the NAACP in 1939 and had served as branch secretary and chair of a membership drive.) The boycott showed how community groups and a local NAACP branch could undertake a nonviolent campaign to push a civil rights agenda, becoming an initial template for the Montgomery bus boycott of the following year. However, it took until 1962 for full integration of the city’s public transportation.

Civil Rights Movement

During the 1950s new civil rights groups emerged, such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which pushed more direct-action campaigns for integration and voting rights. While the NAACP was more comfortable with legal strategies, it worked with groups in campaigns like the Crusade for Citizenship in 1958, which used expertise from a range of community organizations to register Black citizens to vote.

Louisiana branches saw a membership decline in the 1950s. At its peak, in 1948, the organization had 14,119 members. By the end of 1956 state membership declined to 1,698 and seven branches—down from sixty-five—amid a backlash to the civil rights movement that included violence, economic sanctions, and political opposition. The State of Louisiana persecuted the NAACP with legal injunctions to reveal membership lists and in 1958 sought to criminalize the organization as a communist ally with Act 260. (By 1960 federal courts exempted the Louisiana NAACP from such laws).

Post-Civil Rights Movement

Since the 1960s Louisiana branches have focused on employment, housing, voting rights, and voting campaigns (which helped secure Democratic Governor John Bel Edwards re-election in 2019), electoral redistricting, police and prison reforms, food insecurity, and other social justice issues. Branches also highlight annual cultural events like Black History Month and Juneteenth. In 1974 New Orleans was notable for hosting the sixty-fifth annual NAACP national convention. In the 2020s around thirty branches (with youth councils and college chapters) continue operations in the state. Louisiana’s branch records are archived in the Library of Congress. They document race relations throughout the twentieth century and serve as a record of state-level civil rights activism.